If you were born in Pittsburgh 100 years ago, your health outlook would have been very different from today. In 1920, Pittsburgh had the worst recorded infant mortality rate of any major U.S. city, with one in nine babies dying before their first birthday.

|

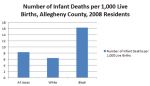

Now in 2011, thanks to antibiotics, vaccines and other modern medical interventions, life expectancy and overall health have vastly improved for our youngest citizens. Unfortunately for African-American children, the gains have not been nearly as great as for Whites. According to the latest Allegheny County figures, Black infants lead all other races in infant death rates (see figure). These disparities continue throughout childhood and have spurred numerous campaigns to improve health in the African-American community and narrow the racial health gap.

To better understand the issue, we talked with Elizabeth Miller, MD, PhD, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and chief of the Division of Adolescent Medicine at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC. Dr. Miller is a pediatrician with special interest and expertise in community health, community-based participatory research and cross-cultural health care education.

What are some of the major health disparities between Black and White children and adolescents?

EM: Wide disparities in health exist locally, nationally, and for just about every health indicator—from low birth weight, infant mortality and teen pregnancy to asthma, obesity and even oral health. For example, although there has been a decline in teen pregnancies overall in this country, the proportion of teen pregnancies among African-American young women is still about three times greater than in Whites.

Why should we be concerned?

EM: Health and wellness are closely linked to important developmental milestones in a young person’s life. More illnesses mean more missed days of school, more problems paying attention in school and a greater risk of dropout. Being hungry, having trouble breathing due to poorly controlled asthma and living in fear of neighborhood violence all contribute to a child’s inability to stay focused in school. For the adult caregiver, having a child who is struggling with illness means lost days of work, high costs of medication and multiple trips to the doctor.

What are the root causes?

EM: Historically, many African American families have confronted barriers, including poverty, poor housing, poor access to high quality care and limited educational opportunities.

How can we begin to address the problem of health disparities?

EM: The statistics may appear overwhelming and disheartening, but we need to examine these profound disparities from the perspective of community strengths and assets rather than failures. Many Pittsburgh communities, for example, are focusing on creating safe places for children to play, establishing farmers markets and neighborhood gardens to increase the availability of fresh produce, increasing outreach efforts to provide universal health insurance coverage for children and utilizing mobile vans and school health centers to facilitate access.

Research evidence has clearly shown that good health promotes positive growth and development in young people. Despite many advances, significant barriers to health still exist for the African-American population. Key action steps lie in mobilizing community resources and promoting collaborations such as this one among the University of Pittsburgh, the Urban League of Greater Pittsburgh and New Pittsburgh Courier to improve the health and safety of our children.