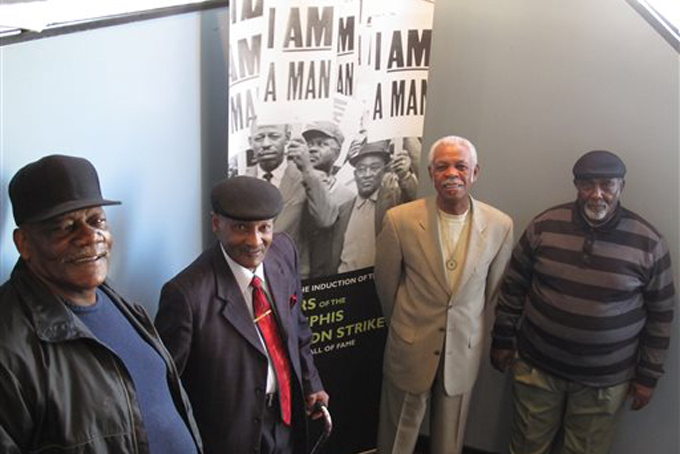

FIGHTING AGAIN–Alvin Turner, the Rev. Leslie Moore, Elmore Nickleberry and Baxter Leach, from left, pose for a photo at the headquarters of Local 1733 of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees on March 14, in Memphis, Tenn. The men participated in a sanitation workers strike in 1968 that drew the support of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., who was assassinated in Memphis on April 4 of that year. The poster includes the strike’s rallying cry, “I am a man.” (AP Photos/Adrian Sainz)

by Adian Sainz

Associated Press Writer

MEMPHIS, Tenn. (AP) — Decades after Martin Luther King Jr. was shot to death here, some of the striking sanitation workers who marched with him are again fighting for their jobs.

In 1968, wages were so low that some workers had to stand in welfare lines to feed their families. Working conditions were so dangerous men were dying on the job. Today, the divisiveness is over whether the people who pick up the garbage should be government employees or whether the service should be turned over to private contractors.

City council members who favor privatization say the city can’t afford to ignore a chance to save $8 million to $15 million in a tight budget.

“It looks like they’re trying to take us down again,” said 81-year-old Elmore Nickleberry, one of the original strikers who still drives a garbage truck at night. Nickleberry and fellow strikers are expected to take part in a march Thursday to honor King’s sacrifice on the 45th anniversary of his death.

The shadow of 1968 still looms over Nickleberry and 1,300 other workers. They were overworked and underpaid, picking up grimy, leaking waste without proper uniforms. They faced the daily risk of severe injury or death while working with malfunctioning garbage trucks.

They took a job no one else wanted, mostly Black workers picking up the trash of White people, serving in what some scholars liken to an urban extension of plantation life on the cotton fields. Their demeaning nickname: “walking buzzards.”

After two workers were crushed to death in a truck’s compactor, the sanitation workers went on strike Feb. 11. They demanded better working conditions, the right to unionize and a raise that would take them off welfare lines. The situation had obvious racial undertones: Most of the workers were Black, and city officials standing against the union were White.

With the slogan “I am a man,” the workers also wanted the respect and dignity that comes with doing a low-paying, back-breaking job with great pride and effort.

King came to Memphis to support them. He delivered his last public speech April 3, declaring, “I’ve been to the mountaintop.”

The next day, standing on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel, King was killed by James Earl Ray.

The assassination led to riots in Memphis and several cities. But the strike, stained forever with King’s blood, turned to victory when the city agreed to a 10-cent raise and other demands, including unionization.

Labor scholars call it a watershed moment.