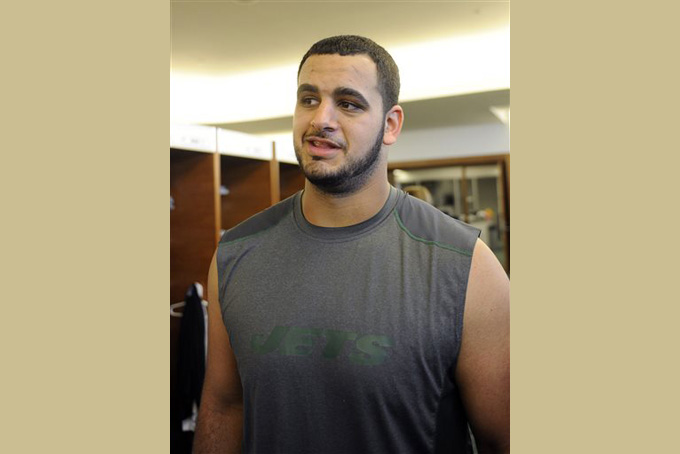

New York Jets’ Oday Aboushi talks to the media in the locker room after NFL football rookie minicamp in Florham Park, N.J. (AP Photo/Bill Kostroun)

by Dennis Waszak Jr.

FLORHAM PARK, N.J. (AP) — The congratulatory messages flooded Oday Aboushi’s Twitter page for a few days after he was drafted by the New York Jets two weeks ago.

Many were happy to see the hometown kid from the New York borough of Staten Island starting his NFL career close to his family and friends. It was the other tweets, first dozens and then hundreds, from places such as Dubai and Saudi Arabia that made the enormity of the situation really sink in.

As a Palestinian-American, the Jets’ offensive lineman is a rarity in the NFL. Aboushi, drafted in the fifth round out after a standout career at the University of Virginia, is one of just a handful of players with that ethnic background.

“People weren’t just talking about me being a New York Jet, but being one of the first Arab-Americans, a Palestinian-American, to be drafted. It’s settling in now. It’s a different feeling, one that I’m embracing and really loving.”

As are Palestinian-Americans around the country. The short list of NFL players with Palestinian backgrounds includes former linebacker Tarek Saleh; former quarterback Gibran Hamdan, who is half Palestinian and half Pakistani; and former defensive lineman Nader Abdallah.

“You don’t see many of us in the sport,” said Aboushi, who signed a four-year deal Friday. “So for me to kind of break that mold and sort of open the door for other people, and show them that it is possible, it’s a great feeling. It’s a pleasure for me, an honor, and I’m happy to be able to be that sort of person for people.”

The 6-foot-5, 308-pound Aboushi is the ninth of 10 children born in Brooklyn to Palestinian parents who came to the U.S. from the town of Beit Hanina in the occupied territory of the West Bank. His family, which now resides in Staten Island, includes lawyers, doctors and accountants, but Aboushi might end up being the greatest success story of all.

And to some, he already is.

“You can’t underestimate what a big deal this is,” said Linda Sarsour, the executive director of the Arab-American Association of New York. “When a lot of Americans think of Palestinians, I feel like there are two images. There’s either the image of a suicide bomber or an image of some poor refugee in Gaza. There’s really nothing in between.

“Oday, being a young Palestinian-American born to Palestinian immigrant parents in New York and gets drafted by the Jets — the dream of every American boy — I think gives a new image to what it is when you think of Palestinian, when you think Arab and when you think Muslim.”

Sarsour, a fellow Palestinian-American, is a long-time friend of Aboushi’s family. Sarsour’s 14-year-old son, Tamir, has been using a photo of him posing with Aboushi, when the offensive lineman helped Staten Island victims of Superstorm Sandy in December, as his Facebook profile picture.

“He’s a role model for young Arab-American and Muslim people who are trying to find their roles in the community, like, who are we and what can we be in this country at this time?” Sarsour said. “It has been such a profound experience. There are not many times that we feel like this, unfortunately. I can’t remember the last time post-9/11 that I’ve felt this proud and so triumphant and victorious as when Oday was drafted by the New York Jets.”

Embracing his background, and being celebrated for it, is nothing new for Aboushi. He was one of about a dozen Muslim athletes honored in 2011 at a reception hosted by then-Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton at the State Department in Washington.

“He’s not the first of his kind, but what makes him different, to me, is that he’s proud of who he is and where he comes from,” Sarsour said. “The fact he’s proud to say he’s Muslim and use a word like ‘Allah,’ which scares a lot of people, and the fact he can’t dance around his name — it’s Oday Aboushi, not something like Michael Smith — makes him different. He’s figured out how to become an All-American football player and how to still be proud of being a Palestinian, and an Arab and a Muslim, and knowing that he is a rising star in a community that needed a rising star.”

Aboushi, who speaks English and Arabic, is a practicing Muslim who went to Xaverian High School, an all-boys Catholic school in Brooklyn — which might seem like a potentially uncomfortable mix.

“It was never an issue,” he said. “It really taught me a lot about the two religions. I didn’t have to, but I attended the masses out of respect. There’s nothing wrong with learning and broadening your horizons. Honestly, besides the football aspect, religion class was actually one of the better aspects of my time at Xaverian.”

At Virginia, the holy month of Ramadan fell during training camp with the football team. As is custom, he fasted from sunrise to sunset, having the school’s trainers monitor his health and nutrition.

“There were some days I’d break it, like during two-a-days where you don’t want to put your body in harm’s way,” Aboushi said. “But for the most part, the trainers did a great job with early breakfasts and late dinners.”

Ramadan ends around Aug. 7 this year, about a week into training camp with the Jets, but Aboushi doesn’t think it will be an issue for him or the team.

He is expected to work mostly at left and right tackle to add depth to the Jets’ revamped offensive line, and possibly some at guard. And, through it all, Aboushi will have plenty of people from all over the map rooting him on.

“This is how you build bridges with the rest of the world, an NFL player is the way you do it,” Sarsour said. “And I think it’s powerful.”