Aki Witherspoon and Chris Winston, both 20, live in transitional housing provided by the nonprofit Familylinks. They submitted their applications for low-income public housing a few days before the list closed. (Photo by Alexandra Kanik / PublicSource)

by Halle Stockton

PublicSource

Nearly 23,000 people live in limbo as they wait for public housing in Pittsburgh and Allegheny County.

The shortage of low-income housing is so bad that, for the first time in 17 years, Pittsburgh’s city housing authority recently closed the waitlist for the majority of its properties.

Waits for housing through both housing authorities could be years.

Aki Witherspoon and Chris Winston — two 20-year-old men who live in transitional housing provided by the nonprofit Familylinks — hope they’ll be lucky. They submitted their applications just a few days before the Pittsburgh list closed in April.

Winston, a shy man who wants to study art, said he has felt like a ghost since his father died, floating through the homes of relatives who couldn’t afford to let him stay or couldn’t stop arguing.

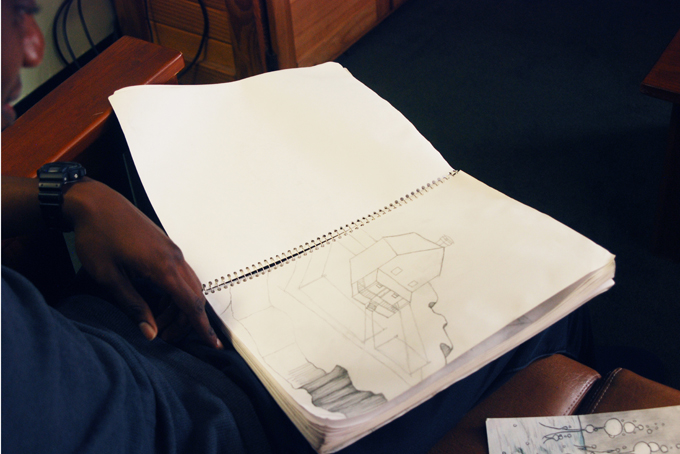

Asked about a pencil drawing of a house in his sketchbook, he said: “It kind of represents a place where I want to be, but it’s hard to get to.”

Chris Winston is an avid drawer who hopes to attend art school. (Photo by Alexandra Kanik / PublicSource)

Tabitha Ceryak, a case manager at Familylinks, expressed her fears for the two, who will need to leave the 18-month transitional housing program in about a year.

“If they don’t find a home, what am I supposed to do with these kids, push them out on the street?” she asked. Public housing is “so backed up I think it’s completely hopeless.”

The nation is in the midst of a public housing crisis exacerbated by a protracted recession and state and federal funding cuts. Housing authorities throughout the country are wading through long waitlists for public housing.

The District of Columbia’s housing authority, for example, closed its waitlist of 70,000 names in April for the first time, according to the Washington Post. An inspector general’s report called for closing the list after estimating an applicant requesting a one-bedroom apartment could be waiting 28 years, the newspaper reported.

Housing officials in Pittsburgh and Allegheny County said it’s not possible to give estimates of wait times because so much depends on the size and location of housing needed.

And there is no centralized database to compare public housing shortages in other cities in Pennsylvania.

There are two primary types of public-housing programs. Low-income public housing refers to residences local housing authorities manage and provide to low-income families, the elderly or people with disabilities at rents that correspond to income.

The Housing Choice Voucher program, formerly known as Section 8, provides rental subsidies to low-income individuals to rent from private landlords.

About 11,600 people are in the queue for low-income housing through the Allegheny County Housing Authority and the Housing Authority of the City of Pittsburgh.

For the voucher program, more than 11,300 people are on the city and county waitlists, which have been closed for some time.

Nearly 8,000 children are among those on waitlists for both programs.

More than 80 percent of families on the waiting lists have “extremely low incomes,” defined as less than 30 percent of the area’s median, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

Ceryak said one woman who applied for low-income public housing in Pittsburgh three years ago was contacted a few months ago by the housing authority about an opening. The woman had already moved to another state.

ABUSE AND HOMELESSNESS

The lack of immediate housing assistance creates desperate situations, said Linda Couch, the coalition’s senior vice president for policy and research.

“This is why you see fires in the winter from people heating (homes with) ovens,” she said. People don’t have enough to pay their bills. “Domestic violence victims continue to stay with their abusers, and obviously the worst situation is people become homeless.”

“There are a lot of people in homeless shelters hoping their number comes up,” said Nan Roman, president of the National Alliance to End Homelessness. “If everybody who was homeless could get housing assistance, homelessness would probably end.”

Yvonne Smith of Pittsburgh is an example of how public housing can help people in dire situations.