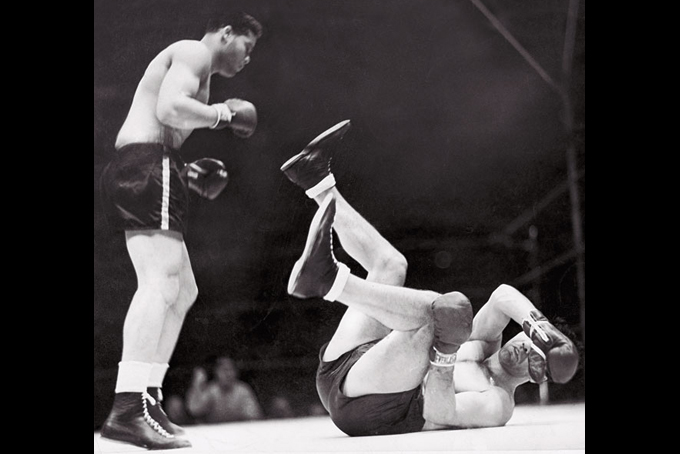

On June 22, 1938, two years after suffering the lone defeat of his prime at the hands of Schmeling — the German puncher who’d been cast as an example of Aryan supremacy — Joe Louis responded with an emphatic first-round knockout before more than 70,000 fans at Yankee Stadium. (AP Photo/File)

by Avis Thomas-Lester

(NNPA)–James “Winky” Camphor , of Baltimore is 86, but he remembers the fight like it happened yesterday.

It was June 22, 1938 and more than 70,000 fight fans crowded into Yankee Stadium to witness a contest that was much more than a boxing bout. It was a grudge match—Black against White, African American versus Aryan, the so-called “Land of the Free” battling Nazi Germany.

For weeks, Joe Louis, the “Brown Bomber,” and his opponent, Max Schmeling, a beefy German who was supported by Adolf Hitler, had been feted by their respective countries. Americans were hopeful that this time Louis would reign victorious over the German boxer, who had

beaten him in 12 rounds two years earlier.

“The first time, Max Schmeling beat Joe Louis because he found a flaw. He worked on that flaw and he knocked him out,” Camphor said. “Joe Louis later promised his manager that it wouldn’t happen again. He said, ‘I want to fight him again. If I fight him again, you won’t have to go up the steps [into the ring] but one time.’ That meant he would win.”

For Whites, a Louis win would strike a blow against fascism and prove that our nation and its ideals were superior to Hitler’s Deutschland dictatorship.

But for African Americans, a victory would offer the world proof that they were equal, that

they could perform as well as, or better than, anybody—given the opportunity and a level playing field.

To the nation, Louis was a hero. To Blacks, he was a savior.

The Black Press ran stories for weeks in advance of the story. The AFRO was in the forefront

of the coverage, doing stories on everything from the amount of time Louis spent with his wife, Marva, leading up to the fight to a piece about his last workout.

“Louis Sees Many Things as Next Wednesday Nears,” said an AFRO headline on the sports page of the June 18, 1938 edition. “Joe Louis (center) looks into the crystal ball at his training camp…probably to see what the outcome of his fight with Schmeling will be next week,” read the

cutline under a picture of Louis flanked by a turbaned magician and his manager, Joe Roxborough. In another photo, Louis stands between then-former heavyweight contender

Harry Wills and Panama Joe Gans.

“Louis, still thinking of the beating Max gave him two years ago, is not passing up anybody’s advice these days—Jack Johnson’s included,” the cutline said.

As the fight drew close, the nation grew frenzied. In an AFRO story on the June 18 sports page, Staff Correspondent Levi Jolley reported on a Louis sparring practice. “Joe Louis…demonstrated a lightning left, but was the receiver of 51 right hand socks during six rounds of boxing before 3,794 paid admissions, who contributed $4,173 at $1.10 a head…At least 1500 persons had to be turned away.”

William Broadwater, 87, of Upper Marlboro, Md., was 12 at the time. He said the entire country was focused on the fight, but Blacks were obsessed with Joe Louis.

“Joe Louis was to Black people what President Obama is to us today,” he said. “We didn’t have any heroes. There were no Black football players or Major League baseball players. We had had Jesse Owens to win big in the 1936 Olympics, but track and field wasn’t as popular as boxing. We hadn’t had a major Black hero since [boxer] Jack Johnson. Joe Louis was that person.”

Broadwater, like Camphor, said Americans of all hues supported Louis.

“It was the first time White people really got behind a Black person in a big way,” he said. “There was the whole thing of Americans against the Nazis. The Germans were supposed to be the superior race, so (White) people didn’t like that.”

On June 25, the AFRO ran a front page story about the international implications of the fight. Though the fight was fought June 22, the newspaper with the results didn’t reach newsstands until July 2.

“NAZIS AID MAX: Say Hitler Fears Loss; Fight May Play Great Part in International Affairs,” the headline read.

“The German government fears the repercussions which may come from a Schmeling defeat by Joe Louis may react with such far reaching effects to the Hitler regime that a special commission comprising physical educational experts, psychologists, and scientific experts has been sent over to assist the challenger, the AFRO-AMERICAN learned this week,” the story said.

“The AFRO informant, who has just arrived from Germany to attend the fight and spend several weeks in America, says that so grave do certain Nazi officials regard the situation that the Goebbels propaganda department has already carefully prepared a flood of material to be used to counteract the effect a Louis victory may have on the politics in central Europe.”

Broadwater said in his hometown of Bryn Mawr, Pa., neighbors started making plans weeks ahead of time to catch the radio broadcast of the contest.

“On my street, Miller Street, we had two radios. My family had one,” he said. “My father used to mess with ours. He had batteries to run it. They looked like car batteries. I can recall the neighbors coming over days before the fight to ask if they could come down to hear the fight.”

The fight took place at the stadium where Jackie Robinson would break the color barrier in professional baseball four years later. One hundred million people around the world listened, according to historical accounts.

In Baltimore, Camphor listened with his mother, Emma, a fight fan, and his father, James Camphor Sr., an amateur boxer who taught him everything he knows about pro boxing. And he knows a lot. He once dabbled in the ring himself. He owns a pair of Muhammed Ali’s boxing gloves. He has traveled to dozens of fights, often with his wife, Peaches, including Ali-Frazier in New York and Tyson-Holyfield in Las Vegas, the same day Tupac was gunned down in front of the MGM Grand.

“He was lying on the sidewalk right in front of us,” Camphor said as Peaches nodded.

That night in 1938, though, Camphor was a pint-sized fight fan among many millions. The battle drew a larger audience than any event in history, according to historical reports.

As the two men climbed into the ring, an announcer noted that Schmeling wore purple trunks and called him “an outstanding contender.” Then, the bell rang.

“One left to the head, one left to the jaw, a right to the head,” the announcer said, outlining the blows that Louis showered on his opponent. “The gentleman (referee) is watching carefully.”

He continued.

“Louis measures him. Right to the body. Left up to the jaw and Schmeling is down. The count is 5, 5, 6, 7, 8…The fight is over on a technical knockout. Max Schmeling is beaten in the first round!”

The fight had lasted a mere two minutes and four seconds.

“Schmeling’s head rocked like a cradle as Louis’s blows found their mark,” said an article published in the AFRO on July 2.

Broadwater remembers that there was complete silence during the fight.

“You could hear a pin drop, but when he won, the whole street yelled,” Broadwater said. “When he had lost two years earlier, it was all boos.”

Camphor recalled the reaction on Born Court in West Baltimore.

“We all burst out into the street and ran around like it was a parade!” he said.

Two years after Jesse Owens embarrassed Hitler at the Summer Olympic Games in Berlin, Louis had defeated another member of his so-called master race.

Broadwater, who went on to join the U.S. Army Air Corps as one of the Black pilots who later would be called the Tuskegee Airmen, said he met Louis several times, typically at posh night spots.

“He took a girlfriend of mine away,” Broadwater said. “She used to write to me in the service. When I came back and went looking for her, my friends said, ‘You can forget that. He bought her a fur coat.’”

Louis did a turn in the military, as well. “Win, lose or draw, Joe Louis will fight his last battle in the prize ring September 29, against Lou Nova. After that Joe will do his stint in the army,” said an AFRO story on Sept. 27, 1941 bearing the title “Joe Louis’s Last Fight.” It noted that he made “$2,000,000 with his fists” in six years.

Louis donated the purses from two fights to military causes. After a stint in the military, he returned to his career in the ring and fought successfully for several years. But in an AFRO story from Oct. 23, 1951 headlined “Don’t Cry For Me—Joe,” Assistant Managing Editor Art Carter detailed the demise of Louis’s career.

“Don’t cry for me…I have no alibi; I was awfully tired…Guess I’m too old,” said Louis, then 37, after he was defeated by Rocky Marciano. “Other fighters, newspapermen and members of Joe’s retinue were visibly showing their sorrow, through tears and saddened faces…This was the end of a great champion.”

Louis worked at the end of his life as a greeter in Las Vegas. He died penniless at age 66 on April 12, 1981. Schmeling, who became his close friend after the second fight, reportedly helped pay for his funeral.

Camphor said he plans to travel to New York on June 22 to see a fight to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the famous fight and to pay homage to Louis.

“When Schmeling beat him the first time, Hitler declared supremacy,” the former educator said. “When Louis beat Scheling in the second fight, he defeated Nazism. He beat Hitler’s best man. He was a hero. He will always be a hero for doing that.”

Reprinted from the Afro-American. Avis Thomas Lester is AFRO Executive Editor

James “Winky” Camphor. (AFRO Photo/Avis Thomas-Lester)