BY THE NUMBERS:

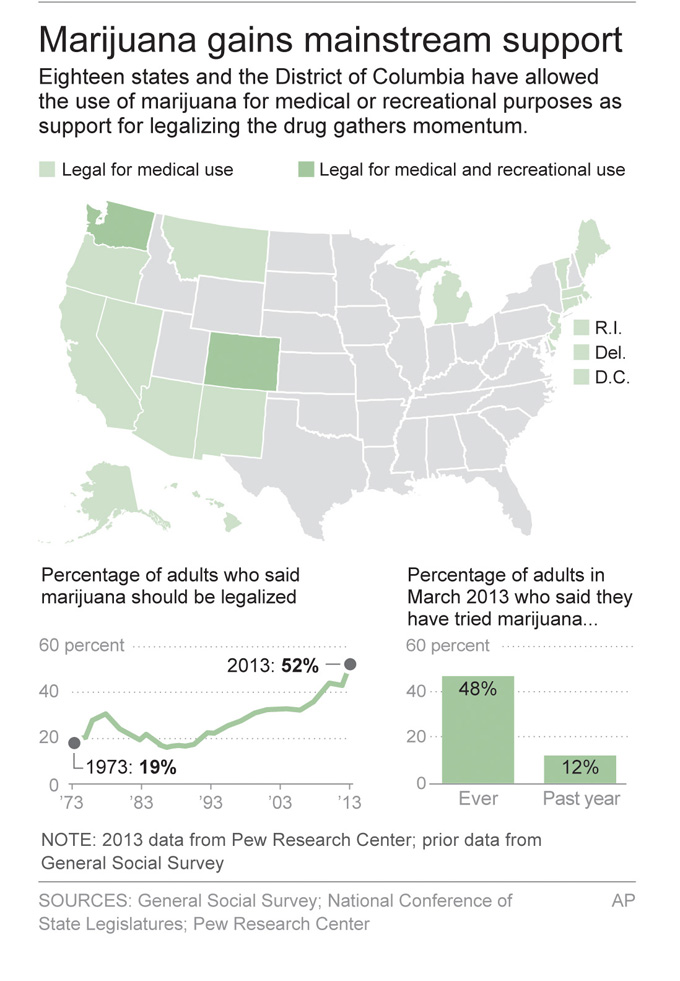

Eighteen states and the District of Columbia have legalized the use of marijuana for medical purposes since California voters made the first move in 1996. Voters in Colorado and Washington state took the next step last year and approved pot for recreational use. Alaska is likely to vote on the same question in 2014, and a few other states are expected to put recreational use on the ballot in 2016.

Nearly half of adults have tried marijuana, 12 percent of them in the past year, according to a survey by the Pew Research Center. More teenagers now say they smoke marijuana than ordinary cigarettes.

Fifty-two percent of adults favor legalizing marijuana, up 11 percentage points just since 2010, according to Pew. Sixty percent think Washington shouldn’t enforce federal laws against marijuana in states that have approved its use. Seventy-two percent think government efforts to enforce marijuana laws cost more than they’re worth.

“By Election Day 2016, we expect to see at least seven states where marijuana is legal and being regulated like alcohol,” says Mason Tvert, a spokesman for the Marijuana Policy Project, a national legalization group.

Where California led the charge on medical marijuana, the next chapter in this story is being written in Colorado and Washington state.

Policymakers there are struggling with all sorts of sticky issues revolving around one central question: How do you legally regulate the production, distribution, sale and use of marijuana for recreational purposes when federal law bans all of the above?

How do you tax it? What quality control standards do you set? How do you protect children while giving grown-ups the go-ahead to light up? What about driving under the influence? Can growers take business tax deductions? Who can grow pot, and how much? Where can you use it? Can cities opt out? Can workers be fired for smoking marijuana when they’re off duty? What about taking pot out of state? The list goes on.

The overarching question has big national implications. How do you do all of this without inviting the wrath of the federal government, which has been largely silent so far on how it will respond to a gaping conflict between U.S. and state law?

The Justice Department began reviewing the matter after last November’s election and repeatedly has promised to respond soon. But seven months later, states still are on their own, left to parse every passing comment from the department and President Obama.

In December, Obama said in an interview that “it does not make sense, from a prioritization point of view, for us to focus on recreational drug users in a state that has already said that under state law that’s legal.”

In April, Attorney General Eric Holder said to Congress, “We are certainly going to enforce federal law. … When it comes to these marijuana initiatives, I think among the kinds of things we will have to consider is the impact on children.” He also mentioned violence related to drug trafficking and organized crime.

In May, Obama told reporters: “I honestly do not believe that legalizing drugs is the answer. But I do believe that a comprehensive approach — not just law enforcement, but prevention and education and treatment — that’s what we have to do.”

Rep. Jared Polis, a Colorado Democrat who favors legalization, predicts Washington will take a hands-off approach, based on Obama’s comments about setting law enforcement priorities.

“We would like to see that in writing,” Polis says. “But we believe, given the verbal assurances of the president, that we are moving forward in Colorado and Washington in implementing the will of the voters.”

The federal government has taken a similar approach toward users in states that have approved marijuana for medical use. It doesn’t go after pot-smoking cancer patients or grandmas with glaucoma. But it also has warned that people who are in the business of growing, selling and distributing marijuana on a large scale are subject to potential prosecution for violations of the Controlled Substances Act — even in states that have legalized medical use.

Federal agents in recent years have raided storefront dispensaries in California and Washington, seizing cash and pot. In April, the Justice Department targeted 63 dispensaries in Santa Ana, Calif., and filed three asset forfeiture lawsuits against properties housing seven pot shops. Prosecutors also sent letters to property owners and operators of 56 other marijuana dispensaries warning that they could face similar lawsuits.

University of Denver law professor Sam Kamin says if the administration doesn’t act soon to sort out the federal-state conflict, it may be too late to do much.

“At some point, it becomes so prevalent and so many citizens will be engaged in it that it’s hard to recriminalize something that’s become commonplace,” he says.