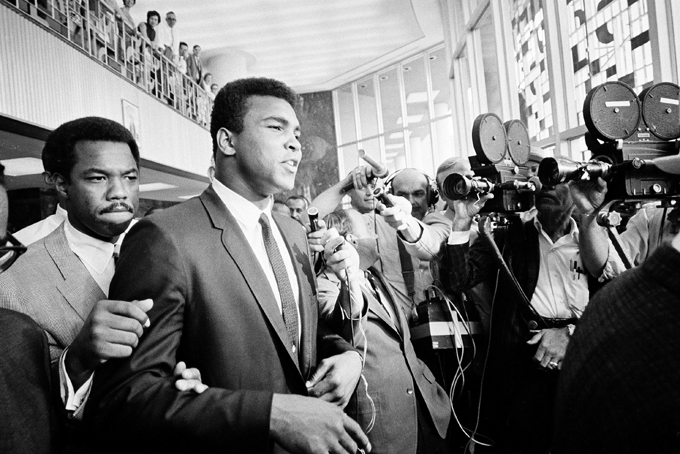

In this June 19, 1967 file photo, heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali has a “no comment” as he is confronted by newsmen as he leaves the Federal Building in Houston during a recess in his trial for refusing induction to the army. (AP Photo/Ed Kolenovsky, File)

by Tim Dahlberg

AP Sports Columnist

He is now so much a part of the nation’s social fabric that it’s hard to comprehend a time when Muhammad Ali was more reviled than revered.

Barely past the opening credits of a new documentary about Ali, though, we get a glimpse of how many Americans felt about him during a tumultuous time in the country’s history.

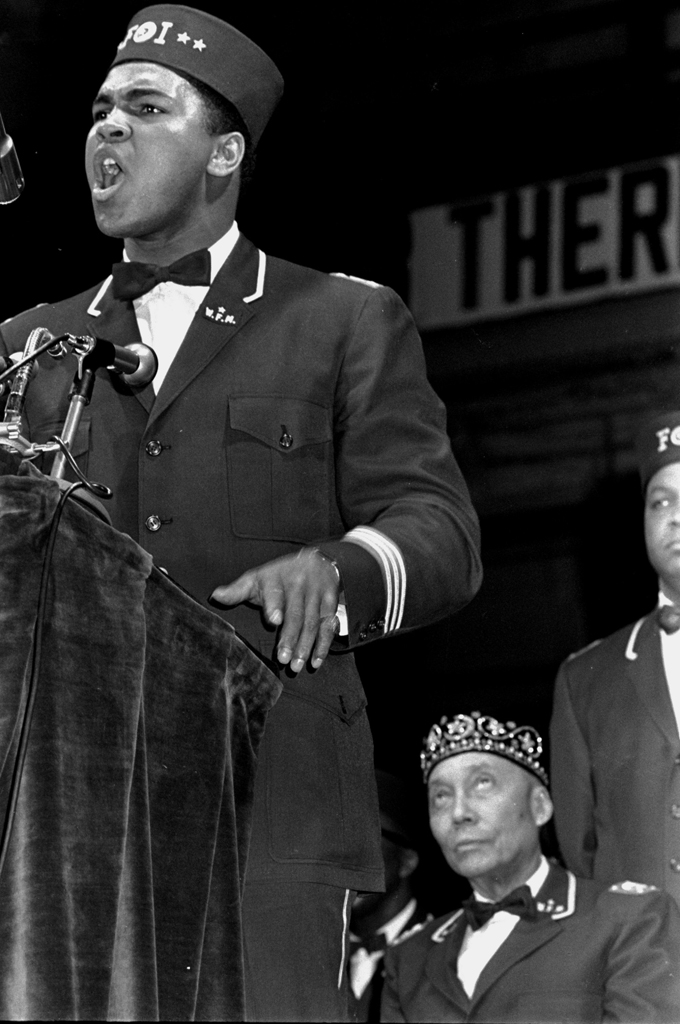

In this Feb. 25, 1968 file photo, former heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali addresses a gathering at a Black Muslim convention in Chicago. Seated behind Ali is Elijah Muhammad, leader of the Nation of Islam. (AP Photo/File)

“I find nothing amusing or interesting or tolerable about this man,” television host David Susskind said, nearly spitting his words out in a 1968 broadcast as Ali looked on. “He’s a disgrace to his country, his race, and what he laughably describes as his profession.”

The scene in “The Trials of Muhammad Ali” — now playing in selected theaters — is then juxtaposed with one of President George W. Bush giving Ali the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2005. From draft-dodging pariah to hero, Ali’s long and sometimes painful journey was finally complete.

For those who didn’t live in the time and are only faintly aware of the tale, it is a remarkable one. For those who grew up in the era and know well Ali’s impact on a country just beginning to come to terms with race relations, it’s a refresher course, complete with clips of Ali at his bombastic — and to some, scary — best.

In this May 25, 1965 file photo, heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali stands over fallen challenger Sonny Liston in Lewiston, Maine. (AP Photo/John Rooney, File)

“I don’t have to be what you want me to be,” Ali is shown telling reporters the morning after his first fight with Sonny Liston in 1964, when he announced to the world he was a follower of the Nation of Islam.

Boxing fans were already wary of his involvement with the Black Muslim movement, but he became a pariah to even more when he refused induction to the Army at the height of the Vietnam War as a conscientious objector, famously saying, “I ain’t got no quarrel with the Viet Cong.”

Banned from boxing and facing five years in prison, he spent three prime fighting years on the sideline while the courts debated what to do with him. Once the heavyweight champion of the world, he became a speaker on college campuses to make a living and keep his cause before the public.

“You’re talking about a man being hit with the war situation and taking a stand along with his involvement with the Nation of Islam. It was new turf,” said Khalilah Camacho-Ali, his wife at the time, who is interviewed in the film. “He was comfortable making his decisions, but the thing that was hard to bear was whether he would fight again. It didn’t look like a hopeful battle.”

Ali would eventually win the battle, and go on to not only regain the heavyweight title but become the most famous athlete of his time. The U.S. Supreme Court finally took up his case and reversed his conviction on a technicality in 1971 in a decision that surprised some considering the tenor of the times.

The decision itself is also the subject of a drama that airs Saturday night on HBO. “Muhammad Ali’s Greatest Fight” uses actors including Christopher Plummer, Ed Begley, Jr. and Peter Gerety to play Supreme Court justices, but Ali himself is taken from the clips of the era at his oratorical best.

“Why tell his story when he tells it himself?” said Shawn Slovo, the movie’s writer.

But tell a story the HBO movie does, though some liberties are taken for entertainment’s sake. Among them are the justices being shown at one point gathering in the basement of the Supreme Court building to watch sex movies for a case before them on pornography, and a clerk smoking marijuana in a court bathroom.

It’s surprisingly engrossing, though, for a movie that revolves almost entirely around the legal process inside the court building. At the center of it is a clerk for Justice John Harlan II, who convinces him to switch his vote so that Ali’s conviction would be overturned on a technicality and he would not have to go to prison.

The movie and the documentary aren’t related except that they both feature Ali. They do, however, share funny clips from when Ali — complete with big Afro and beard — is shown singing in the 1969 Broadway musical “Buck White.” A man had to make a living, but Ali’s days as an actor were numbered when the play closed after seven performances.

Camacho-Ali, who was married to Ali from 1967-77, said she never gave up hope during her husband’s dark period that he would be allowed to fight again, though Ali himself had his doubts.

“My frame of mind was more positive than his was and it helped keep him afloat,” she said. “The best thing for Ali at the time was to keep him focused on his family life. That’s all we had to work with.”

Camacho-Ali hasn’t seen her former husband — now married to his fourth wife, Lonnie — since they both attended Joe Frazier’s funeral in 2011. But she still feels protective of Ali, who she had four children with, and believes the documentary is a way of educating people to the times they lived in and what they went through.

“I’m tired of people giving the wrong information,” she said. “You’re talking about one of the most famous people in recent history. The facts should be correct.”

This undated publicity photo provided by HBO shows Frank Langella, left, and Christopher Plummer in a scene from “Muhammad Ali’s Greatest Fight,” directed by Stephen Frears. The drama about the Supreme Court decision on the boxer’s conscientious objector status, debuts Saturday, Oct. 5, 2013, on HBO and stars Plummer, Langella and Benjamin Walker. (AP Photo/HBO, Jojo Whilden)