Pros go from rags-to-riches-back-to-rags

SECOND OF A 3-PART SERIES

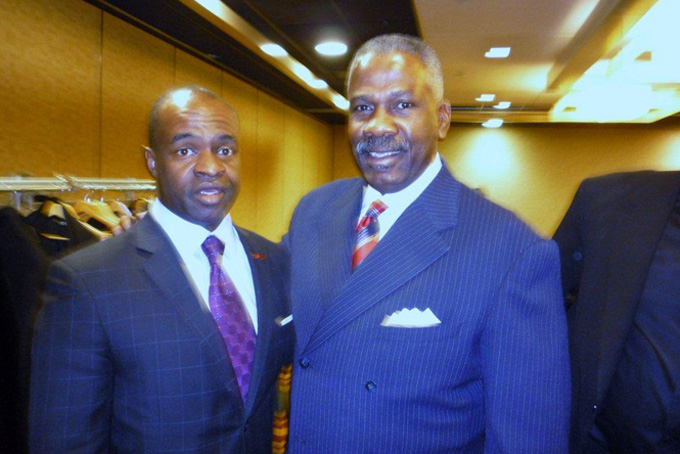

Editors Note: As a sports agent, Attorney Everett Glenn has negotiated contracts for some of the biggest names in sports, including NFL Hall of Famers Jerry Rice, Richard Dent and Reggie White as well as 11 first round draft picks. He has also had a front-row seat observing how Black athletes and the Black community are exploited, enriching others while leaving the community and, ultimately, the athletes themselves destitute. Sports is a $500 billion per year industry, but few of those dollars return to the African-American community. According to Sports Illustrated, by the time former NFL players have been retired for two years, nearly 80 percent of them “have gone bankrupt or are under financial stress because of joblessness or divorce.” Within five years of retirement, approximately 60 percent of former NBA players are broke. After more than three decades of looking at this tragedy on the collegiate and professional level, Attorney Glenn pulls back the cover on these practices in a 3-part series for the NNPA News Service and, more importantly, outlines what can be done to halt the wholesale exploitation and initiate economic reciprocity.

WASHINGTON (NNPA) – There have been so many former professional athletes in the news recently who have gone from rags-to-riches-back-to-rags again that they could form their own reality show.

Future Hall of Famer Terrell Owens, for example, accumulated some amazing stats during his 15-year NFL career as a wide receiver: second in league history with 15,934 yards, tied for second with 153 touchdowns and sixth with 1,078 catches.

Instead of talking about his on-field accomplishments, however, fans and sportscasters are talking about his interview with Dr. Phil in which he disclosed that he has lost all of his money, estimated to be between $80 million and $100 million.

After falling behind in child support payments to baby mama Kimberly Floyd, a judge ordered T.O. to complete eight hours of community service, which he performed at a Los Angeles Goodwill store.

And there was former NBA baller Allen Iverson, who says he’s broke after earning more than $150 million during his 15-year NBA career, plus a Reebok endorsement worth $50 million . At his divorce proceedings last year, Iverson shouted to his estranged wife, Tawanna, “I don’t even have money for a cheeseburger.”

Hundreds of other former professional athletes – including former Boston Celtic Antoine Walker, boxer Mike Tyson and track star Marion Jones – could be added to the list. And no matter how often their stories are told, we’re likely to see still more stories of personal and financial ruin.

Let’s be clear: athletes who spend lavishly and regularly travel with as many as 50 freeloaders must accept direct responsibility for their current predicament. But they are not the only ones at fault in a system that routinely separates Black athletes from their community while they are still enrolled in college, steering them away from wives who look like them and White agents who don’t share their culture.

What separates the exploitation of the Black athlete at the professional level, where Black athletes make up roughly 80 percent of the NBA and 70 percent of the NFL, is money. Big, big money. And big money in the hands of unsophisticated Black athletes is a train wreck waiting to happen, attracting agents, financial advisers and other professionals who view them as easy prey.

In the typical scenario, a “qualified” agent lands a client and then quickly recommends a financial adviser. Or, vice versa. Maybe the pair recruits together. Maybe they just vouch for “their guy.” Maybe there are kickbacks. Maybe there is the expectation of future swaps. However it goes down, in the end, a player thinks he has two sets of independent, trustworthy eyes on his money when, in fact, he has none.

How is it that well-paid agents and advisers are absolved of any responsibility and/or liability for their complicity in players’ financial fatalities? We read about Iverson’s financial problems with no mention of his agent, Leon Rose of CAA. We know about Terrell Owens’ money worries but Drew Rosenhaus, his “super agent,” isn’t held accountable. If you check the websites of major agents, they all in one form or another claim a “family-first” approach. The only family they put first is theirs.

The same media that ignores their colossal failures had no problem demonizing Don King. He single-handedly changed the economics of the fight game with such promotions as the “Rumble in the Jungle” and the “Thrilla in Manila,” yet White-owned corporate media have portrayed King as an unrepentant villain. But they don’t make similar claims about his chief rival, Bob Arum, whom promoter Dana White accused of “sucking the life out of the sport (boxing).”

Because coaches and university boosters, most of whom are White, steer Black athletes to White agents, many Black agents – such as Angelo Wright, Al Irby, Alvin Keels, Kennard McGuire and Tony Paige – don’t get a fair opportunity to represent most Black athletes. My guess is that Black player agents represent less than 15 percent of all NBA and NFL players.

According to Sports Illustrated, by the time former NFL players have been retired for two years, nearly 80 percent of them “have gone bankrupt or are under financial stress because of joblessness or divorce.” Within five years of retirement, approximately 60 percent of former NBA players are broke. By virtue of their numbers, it’s clear that Black agents are not leading a parade of Black athletes into bankruptcy or financial distress nor are they sitting by silently watching their clients commit financial suicide.