When she was a baby, Kayla Bowyer of Pittsburgh was adopted by her grandparents because her mother was in and out of Allegheny County Jail.

Her grandfather died when she was 10 and her ‘Grams’ had to go to work to support Bowyer, her younger brother and three cousins.

Though the presence of adults in her home changed, she was not alone.

In 2004, she and her brother were matched with Yolanda and Ron Bennett through Amachi Pittsburgh, a nonprofit organization that pairs mentors with children of an incarcerated parent.

“Our mentors were husband and wife. And so sometimes … we would all be together. It was kind of like a second family,” said Bowyer, now 24.

An estimated 1.7 million children in the country have a parent in prison, according to a new report from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Millions more may have a parent in county jail.

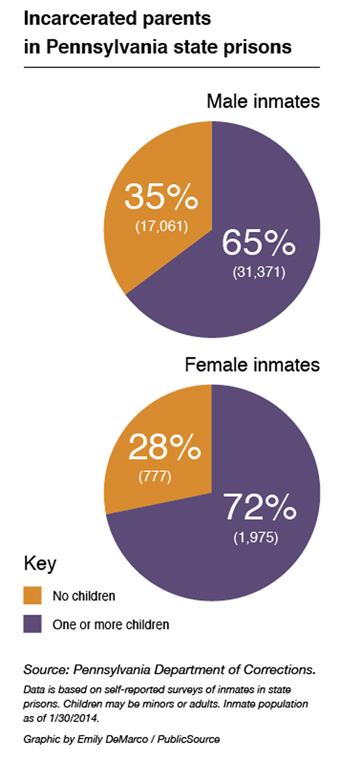

In Pennsylvania, about 81,100 children have a parent in state prison, according to the latest data from the state’s Department of Corrections. Those numbers do not include children with parents in federal prisons or county jails.

Some experts said the children of incarcerated parents are often shunned or bullied.

“You should care about the needs of these kids, because you care about the needs of all children,” wrote Judge Kim Berkeley Clark of the Allegheny County Common Pleas Court in an email. “The children don’t have a say in who their parents are or where their parents are.”

Bowyer pointed out that children of incarcerated parents are — and are not — like other kids. “They’re facing a very unique problem,” said Bowyer, who now works for Amachi Pittsburgh, the organization that brought the Bennetts into her life.

“If we can match them with a mentor, they can sort of look to their mentor as additional support, and not necessarily as a replacement for their parent.”

Some groups of children are more likely than others to have a parent in prison.

“African-American youth are more than seven times as likely as White youth and nearly three times as likely as Hispanic youth to have a parent in prison,” the report said.

Children of an incarcerated parent, in general, suffer higher risks of coping with depression, substance abuse, anxiety and behavioral problems at home or at school.

Clark said she routinely sees evidence in the courtroom of many of the challenges these children face. She detailed them in an email:

Clark is the chairwoman of Dependent Children of Incarcerated Parents Workgroup, an initiative of the Pennsylvania State Roundtable.

‘He’s my dad’

Dyllon Varner, 15, lives with his mom in Munhall, a borough in Allegheny County, because his dad is in prison. (Amachi Pittsburgh declined to disclose the crimes for which the parents of children in the program were serving sentences.)

On a recent Monday, Dyllon and his mentor, Adam Matz, went on the Monongahela Incline in Pittsburgh, a cable-railway car that climbs the steep slope of Mount Washington on tracks.

“What do you think of the ride?” Matz asked as they waited for the car to begin its descent.

“It’s awesome,” Dyllon said.

The two have been getting to know each other for about three months, Matz said. Together they planned a list of activities. Now, they can check off their list riding the incline.

Dyllon likes to draw, skateboard and snowboard. At his job, he mixes pizza dough from scratch. Among his favorite things to do: Hanging out with his friends in Munhall, just like any ninth grader.

He takes a moment before answering a question about his dad.

“There’s not really much to say,” Dyllon said. “He’s my dad. I love him. I miss him, but I don’t really know the kind of guy he is.”

Dyllon and his dad exchange letters and talk on the telephone; the last time he saw his dad was when he was about 8.

Instilling trust

In the northeastern part of the state, between 25 and 30 percent of the 218 children currently enrolled in the Scranton-based Big Brothers Big Sisters of Lackawanna, Susquehanna, Wayne and Pike Counties have at least one incarcerated parent, said Cynthia Beeman, the program director.

In the northeastern part of the state, between 25 and 30 percent of the 218 children currently enrolled in the Scranton-based Big Brothers Big Sisters of Lackawanna, Susquehanna, Wayne and Pike Counties have at least one incarcerated parent, said Cynthia Beeman, the program director.

For the children, there is a stigma attached to having a parent behind bars — if they know, she said.

“There are a lot of them where the parents haven’t told them the other parent is incarcerated. Many times … they tell them they are on vacation or they are not able to come home,” Beeman said.

“Sometimes, the children figure it out on their own and then it’s kind of a dirty little secret: ‘I can’t tell anybody because I’m not supposed to know.’ It creates a lot of stress in a child’s life.”

Their problems don’t end when the parents return. They could continue to have difficulty mending a broken bond between family members.

Family or foster care?

“There’s an adjustment period in terms of how they’re treated in the community and still having difficulties in the family,” said Tanya Olaviany, program director of Big Brothers Big Sisters (BBBS) of the Bridge, a Wilkes-Barre-based program of Catholic Social Services of the Diocese of Scranton.

“A lot of it depends on the type of support they have.”

A strong support system can be made up of trusted guardians, family members or community volunteers.

Programs, such as BBBS, geared toward helping troubled youth, don’t aim to simply occupy their time, Olaviany said.

The one-on-one relationships offer children a person they can talk with about their struggles. Then, they feel there are people they can rely on.

Some killed in prison

Bowyer said she never pretends to know everything kids like Dyllon or the about 100 others involved in Amachi Pittsburgh are going through. Each child’s situation is unique.

“I was lucky enough to have my mother return,” she said. “Some kids in our program are not that lucky. Some parents are serving life sentences. Some parents are killed in prison.”

Still, Bowyer said she knew some people looked at her mother just as a criminal.

“But she was still my mother, she said. “So I looked at her as a great person,” Bowyer said. “It’s kind of hard to explain.”

Bowyer said working for Amachi Pittsburgh, a faith-based organization that is part of a national program that started in Philadelphia, is one of the best things that has happened to her.

And her mentor, Yolanda Bennett — who Bowyer described as a funny, relatable person who never tried to “take the place” of her mother — was equally happy to hear where Bowyer now works.

The Bennetts moved from the North Side of Pittsburgh to Virginia. But distance hasn’t dampened their relationship with Bowyer.

“I love Kayla,” said Yolanda Bennett. “She is the most wonderful, bright young lady that I’ve ever met.”

David Singleton of the Scranton Times-Tribune also contributed to this report.

Reach Emily DeMarco at 412-315-0262 or edemarco@publicsource.org.