A guide to manipulating bigotry to support an agenda, while insisting you didn’t mention race.

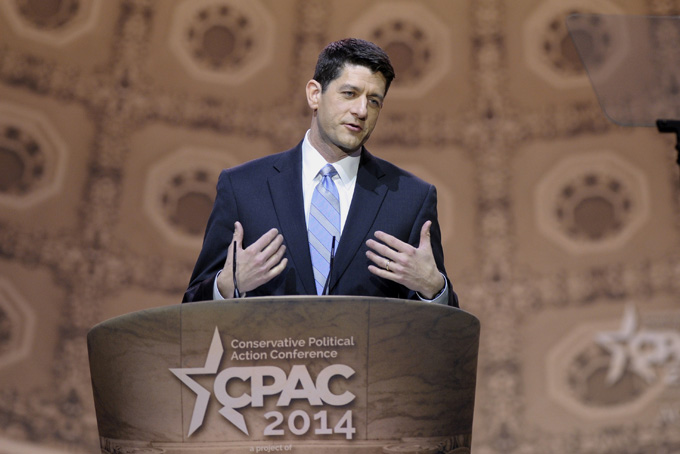

When Paul Ryan talked about a “real culture problem” in “our inner cities in particular” this week, he wasn’t the first American politician to be slammed for using racially coded language to get a point across. Far from it.

Ian Haney López, author of Dog Whistle Politics: How Coded Racial Appeals Have Reinvented Racism and Wrecked the Middle Class, says it’s not just the promotion of old-fashioned racial stereotypes that we need to worry about. Rather, he argues, it’s the manipulation of racism in service of very specific goals.

López’s book focuses on elected officials’ ability to tap into bias without being explicit about it, all to gain support for what he calls “regressive policies,” which, ironically, hurt working-class white people as much as people of color.

“This sort of coded speech operates on two levels,” he says. “It triggers racial anxiety and it allows plausible deniability by crafting language that lets the speaker deny that he’s even thinking about race.”

It’s disturbing and frustrating, and more than ever, it’s what racism sounds like and how politics works.

To understand how outright racist language has gone underground but is working as hard as ever to drum up support for conservative policies, the author says, you just have to look at this list of sneaky code words and phrases that politicians throughout history have loved, and what they really mean:

1. ‘Inner City’

Ryan’s statement, which he later said he regretted, is a perfect example of the way public expressions of racism have evolved, says López. “You can’t publicly say black people don’t like to work, but you can say there’s an inner-city culture in which generations of people don’t value work.” The goal here, he says, isn’t to demonize minorities—far from it—but to demonize a government that helps the middle class (and if the people Americans have historically associated with inner cities have to be used in the process, so be it).

2. ‘States’ Rights’

Totally innocent and nonracial, right? Not so much. López says we first heard this from Barry Goldwater, who was running on a very unpopular platform critical of the New Deal, during the 1964 presidential election. “He makes the critical decision to use coded racial appeals, trying to take advantage of rising racial anxiety in the face of the civil rights movement,” says López. In other words, while “states’ rights” is a pretty racially neutral issue, you just have to look at what was happening at the moment to realize that everyone knew it translated to the right of states to resist federal mandates to integrate schools and society.

3. ‘Forced Busing’

López calls this phrase, which, on its face, was racially neutral, “the Northern analog of states’ rights,” which “allowed the North to express fevered opposition to integration without having to mention race.” After all, kids had been bused to school for quite a while. It was only when the plan took on a racial edge that it became controversial. Politicians didn’t have to say that outright, though—they simply dropped in the phrase to trigger resentment and gain supporters.

4. ‘Cut Taxes’

Dog-whistle politics is partly about demonizing people of color, but it’s also about demonizing government in a way that helps the very rich, says López. So, when Ronald Regan said “cut taxes,” what he was communicating to the middle class was, “so your taxes won’t be wasted on minorities.” A key Reagan operative admitted as much in an interview quoted in Lopez’s book, saying, ” ‘We want to cut taxes’ … is a whole lot more abstract than, ‘Nigger, nigger.’ ” It continues to be more abstract, and it continues to work.

5. ‘Law and Order’

This phrase, says López, is a way to draw on an image of minorities as criminals that was used by both Reagan and Clinton. He points to an inverse relationship in Congress between conversations about civil rights and criminal law enforcement. “What you see in the 1960s is that opposition to civil rights becomes ‘what we really need is law and order, to crack down’. ” Of course, the latter is less controversial and, at least on its surface, avoids the issue of race.

6. ‘Welfare’ and ‘Food Stamps’

Welfare, says López, was broadly supported during the New Deal era when it was understood that people could face hardships in their lives that sometimes required government assistance, and, in fact, was purposely limited to white recipients. In this context, it wasn’t heavily stigmatized. Fast-forward to the 1960s, when Lyndon Johnson made it clear that he wanted it to have a racial-justice component. “Then it becomes possible for conservatives to start painting welfare as a transfer of wealth to minorities,” says Lopez. Remember those Reagan speeches about welfare queens? Today, says López, we hear “food stamps” used similarly.

7. ‘Shariah Law’

We first started hearing about this alleged threat to American justice in the wake of the Sept. 11 attacks, says López, when the Bush administration became intent on linking the war in Iraq to hijackers who were from Saudi Arabia. “To get there, you convince America that this threat is internal as well—new brown immigrants who are threatening the heartland,” he says. “A prime example is Kansas prohibiting courts from drawing on Shariah law—it’s not a threat at all. The point isn’t the reality; it’s the racial frame. The point is, these brown Muslim people are infiltrating our country, so be afraid, and vote for politicians who will support the right wing.”

8. ‘Illegal Alien’

This phrase, says López, is a perfect dog whistle, which triggers fears about immigrants as criminals, taking advantage of welfare and disrespecting the American way of life. But somehow the concerns are always pointed at the Mexican border instead of the one we share with Canada. “It’s racial rhetoric about Latinos that is now being couched in this seemingly racially neutral language, and harnessed to support fear to get people to support conservative policies.”

Jenée Desmond-Harris is The Root’s senior staff writer. Follow her on Twitter.