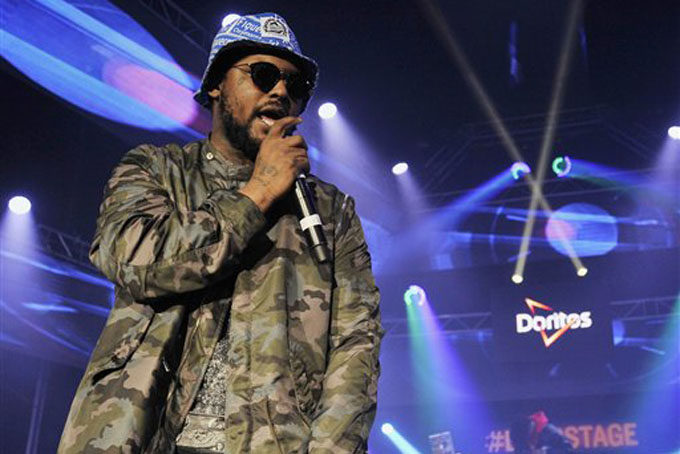

AUSTIN, Texas (AP) — Rapper ScHoolboy Q had a great time at his first South By Southwest a few years ago, but found himself getting angry this year as he played a series of shows at the annual music conference and festival.

Everywhere he turned, his fans were standing outside venues festooned with corporate branding, unable to enter because they didn’t have a formal invite.

“It’s stupid. They changed it all up. It’s corporate,” he said as he prepared for a show Saturday. “I don’t ever want to come back unless they change it to where the fans are in. I’m tired of performing and seeing my fans outside the gate. … That’s not fair. It’s not about the fans no more, it’s all about money, who can give you the best look.”

As South By Southwest shuttered its 28th year Sunday, participants debated the growing corporate influence on the conference. Critics say SXSW has evolved past its core mission: to help new bands get discovered. Instead, they say, the media focus has shifted to already-established stars such as Jay Z, Kanye West, Lady Gaga, Coldplay, CeeLo Green, Rick Ross, Keith Urban and many more whose heavily promoted appearances are underwritten by international brands.

It’s poor vs. the 1 percent in miniature, and this change in vibe is relatively new. Even those who’ve found the spotlight before say it’s getting harder to break through.

“This South By feels different for us,” said Adam Thompson, singer-guitarist for Scottish band We Were Promised Jetpacks, which made its fourth appearance at the festival. “It does feel like the first two were amazing to help us play shows and get people to notice us. Even stupid stuff like our name was funny, so people would come see us.

“We just came off the back of a really nice tour with some nice venues, and now we’re sort of thrown off the deep end. Sometimes you’re thinking, ‘I’d like to play in a nice club with a soundcheck instead of not being able to hear … on stage.'”

An hour later, the band had technical and sound troubles after hastily assembling its gear, but left the venue with a few more fans by powering through their fourth of five sets in three days.

We Were Promised Jetpacks’ experience was far different from the major pop stars, who starred at some of Austin’s nicest venues with state-of-the-art sound and lighting systems.

James Minor, general manager of the music portion of the festival, says he still thinks the focus is aimed at discovery, and that organizers are sensitive to groups most music fans have yet to hear about.

“I feel incredibly responsible for all these acts that we invite because it costs a lot of money to get here,” Minor said. “If somebody’s going to travel to Austin, you want to make sure that they’re playing in front of people, that they’re going to get something out of South By Southwest. We invite acts we feel have already gained some kind of momentum that could kind of use the festival as a platform to help them up to the next level.”

The initial hurdle is the festival’s sheer popularity. It has grown exponentially since it first started in 1987 with 177 acts appearing on 15 stages. This year more than 2,300 acts performed on 111 stages.

Where should a journalist put the emphasis: On bands that generate thousands of clicks or a little bit of buzz?

“That’s an easy choice to make,” Minor said. “It’s a journalist’s responsibility to do what needs to be done, to go see those young bands and help them out.”

Lady Gaga, who played a Doritos-sponsored event that required entrants to perform certain acts and post them to social media, bristled at the idea that corporate sponsorship is a bad thing, dismissing the complaints with an expletive. She said critics were ignorant of the current state of the music business.

“The truth is without sponsorship, without these companies coming together to help us, we won’t have any more artists in Austin, we won’t have any festivals because record labels don’t have any (expletive) money,” she said.

The new, corporate-fueled reality at SXSW has many rethinking the approach. Jim Merlis, a publicist who represents several bands in attendance, counsels managers to skip the conference unless they have something worth paying attention to.

“My advice is what you can’t do is start a spark at South By Southwest,” he said. “You better have the spark already there, and if you pour a little gasoline on it the spark will make a fire. If you have nothing going on, if you’re between albums, if you’re about to release an album and you’re a brand new band and you’ve never really been written up anywhere, then don’t go.”

Even with something to pitch it can be risky: “You could be playing against some really big stars and you’re just not going to be heard. It’s always a risk, there’s very few absolute slam dunks.”

Aloe Blacc, who sings the hit “The Man,” had one of those slam-dunk experiences this year, but he’s been on the other side of the equation, too.

“South By Southwest is boom or bust, and you can be on either side of the moon, seriously,” Blacc said. “I’ve seen it and I don’t envy the bands who spend their last dollar to get here and play for no one.

“At the same time, everybody’s got to take a chance to get exposure and if you come to South By, come with a plan about how you’re going to be noticed. Otherwise you can be noticed at home.”

___

Online:

___

Follow AP Music Writer Chris Talbott on Twitter at: https://twitter.com/Chris_Talbott.