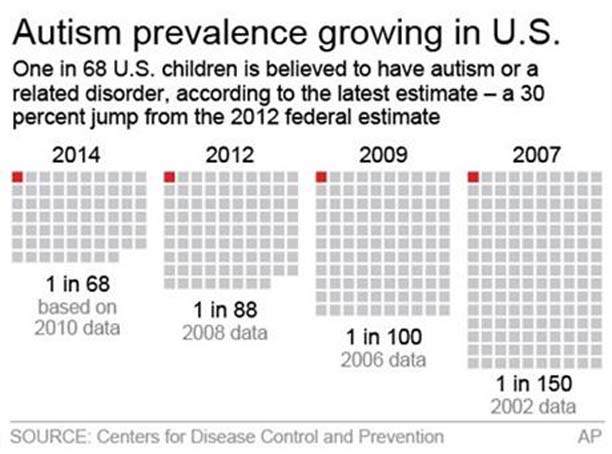

NEW YORK (AP) — The government’s estimate of autism has moved up again to 1 in 68 U.S. children, a 30 percent increase in two years.

But health officials say the new number may not mean autism is more common. Much of the increase is believed to be from a cultural and medical shift, with doctors diagnosing autism more frequently, especially in children with milder problems.

“We can’t dismiss the numbers. But we can’t interpret it to mean more people are getting the disorder,” said Marisela Huerta, a psychologist at the New York-Presbyterian Center for Autism and the Developing Brain in suburban White Plains, N.Y.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released the latest estimate Thursday. The Atlanta-based agency said its calculation means autism affects roughly 1.2 million Americans under 21. Two years ago, the CDC put the estimate at 1 in 88 children, or about 1 million.

The cause or causes of autism are still not known. Without any blood test or other medical tests for autism, diagnosis is not an exact science. It’s identified by making judgments about a child’s behavior.

Thursday’s report is considered the most comprehensive on the frequency of autism. Researchers gathered data in 2010 from areas in 11 states — Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Georgia, Maryland, Missouri, New Jersey, North Carolina, Utah and Wisconsin.

The report focused on 8-year-olds because most autism is diagnosed by that age. The researchers checked health and school records to see which children met the criteria for autism, even if they hadn’t been formally diagnosed. Then, the researchers calculated how common autism was in each place and overall.

The CDC started using this method in 2007 when it came up with an estimate of 1 in 150 children. Two years later, it went to 1 in 110. In 2012, it went to 1 in 88.

Last year, the CDC released results of a less reliable calculation — from a survey of parents — which suggested as many as 1 in 50 children have autism.

Experts aren’t surprised by the growing numbers, and some say all it reflects is that doctors, teachers and parents are increasingly likely to say a child with learning and behavior problems is autistic. Some CDC experts say screening and diagnosis are clearly major drivers, but that they can’t rule out some actual increase as well.

“We cannot say what portion is from better diagnosis and improved understanding versus if there’s a real change,” said Coleen Boyle, the CDC official overseeing research into children’s developmental disabilities.

For decades, autism meant kids with severe language, intellectual and social impairments and unusual, repetitious behaviors. But the definition has gradually expanded and now includes milder, related conditions.

One sign of that: In the latest study, almost half of autistic kids had average or above average IQs. That’s up from a third a decade ago and can be taken as an indication that the autism label is more commonly given to higher-functioning children, CDC officials acknowledged.

Aside from that, much in the latest CDC report echoes earlier findings. Autism and related disorders continue to be diagnosed far more often in boys than girls, and in Whites than Blacks or Hispanics. The racial and ethnic differences probably reflects White communities’ greater focus on looking for autism and White parents’ access to doctors, because there’s no biological reason to believe whites get autism more than other people, CDC officials said at a press briefing Thursday.

One change CDC officials had hoped to see, but didn’t, was a drop in the age of diagnosis. Experts say a diagnosis can now be made at age 2 or even earlier. But the new report said the majority of children continue to be diagnosed after they turn 4.

“We know the earlier a child is identified and connected with services, the better,” Boyle said.

The American Academy of Pediatrics issued a statement Thursday, saying the nation needs to step up screening for the condition and research into autism’s causes.

“It’s critical that we as a society do not become numb to these numbers,” said Dr. Susan Hyman, head of the group’s autism subcommittee.