MEXICO CITY (AP) — Nobel laureate Gabriel Garcia Marquez crafted intoxicating fiction from the fatalism, fantasy, cruelty and heroics of the world that set his mind churning as a child growing up on Colombia’s Caribbean coast.

One of the most revered and influential writers of his generation, he brought Latin America’s charm and maddening contradictions to life in the minds of millions and became the best-known practitioner of “magical realism,” a blending of fantastic elements into portrayals of daily life that made the extraordinary seem almost routine.

In his works, clouds of yellow butterflies precede a forbidden lover’s arrival. A heroic liberator of nations dies alone, destitute and far from home. “A Very Old Man With Enormous Wings,” as one of his short stories is called, is spotted in a muddy courtyard.

Garcia Marquez’s own epic story ended Thursday, at age 87, with his death at his home in southern Mexico City, according to two people close to the family who spoke on condition of anonymity out of respect for the family’s privacy.

Known to millions simply as “Gabo,” Garcia Marquez was widely seen as the Spanish language’s most popular writer since Miguel de Cervantes in the 17th century. His extraordinary literary celebrity spawned comparisons with Mark Twain and Charles Dickens.

“A thousand years of solitude and sadness because of the death of the greatest Colombian of all time!” Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos said on Twitter. “Such giants never die.”

His flamboyant and melancholy works — among them “Chronicle of a Death Foretold,” ”Love in the Time of Cholera” and “The Autumn of the Patriarch” — outsold everything published in Spanish except the Bible. The epic 1967 novel “One Hundred Years of Solitude” sold more than 50 million copies in more than 25 languages.

The first sentence of “One Hundred Years of Solitude” has become one of the most famous opening lines of all time: “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendia was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.”

With writers including Norman Mailer and Tom Wolfe, Garcia Marquez was also an early practitioner of the literary nonfiction that would become known as New Journalism. He became an elder statesman of Latin American journalism, with magisterial works of narrative non-fiction that included the “Story of A Shipwrecked Sailor,” the tale of a seaman lost on a life raft for 10 days. He was also a scion of the region’s left.

Shorter pieces dealt with subjects including Venezuela’s larger-than-life president, Hugo Chavez, while the book “News of a Kidnapping” vividly portrayed how cocaine traffickers led by Pablo Escobar had shred the social and moral fabric of his native Colombia, kidnapping members of its elite. In 1994, Garcia Marquez founded the Iberoamerican Foundation for New Journalism, which offers training and competitions to raise the standard of narrative and investigative journalism across Latin America.

But for so many inside and outside the region, it was his novels that became synonymous with Latin America itself.

“The world has lost one of its greatest visionary writers — and one of my favorites from the time I was young,” President Barack Obama said.

When he accepted the Nobel prize in 1982, Garcia Marquez described the region as a “source of insatiable creativity, full of sorrow and beauty, of which this roving and nostalgic Colombian is but one cipher more, singled out by fortune. Poets and beggars, musicians and prophets, warriors and scoundrels, all creatures of that unbridled reality, we have had to ask but little of imagination, for our crucial problem has been a lack of conventional means to render our lives believable.”

Gerald Martin, Garcia Marquez’s semi-official biographer, told The Associated Press that “One Hundred Years of Solitude” was “the first novel in which Latin Americans recognized themselves, that defined them, celebrated their passion, their intensity, their spirituality and superstition, their grand propensity for failure.”

The Spanish Royal Academy, the arbiter of the language, celebrated the novel’s 40th anniversary with a special edition. It had only done so for just one other book, Cervantes’ “Don Quijote.”

Like many Latin American writers, Garcia Marquez transcended the world of letters. He became a hero to the Latin American left as an early ally of Cuba’s revolutionary leader Fidel Castro and a critic of Washington’s interventions from Vietnam to Chile. His affable visage, set off by a white mustache and bushy grey eyebrows, was instantly recognizable. Unable to receive a U.S. visa for years due to his politics, he was nonetheless courted by presidents and kings. He counted Bill Clinton and Francois Mitterrand among his presidential friends.

“From the time I read ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude’ more than 40 years ago, I was always amazed by his unique gifts of imagination, clarity of thought, and emotional honesty,” Clinton said Thursday. “I was honored to be his friend and to know his great heart and brilliant mind for more than 20 years.”

Garcia Marquez was born in Aracataca, a small Colombian town near the Caribbean coast on March 6, 1927. He was the eldest of the 11 children of Luisa Santiaga Marquez and Gabriel Elijio Garcia, a telegraphist and a wandering homeopathic pharmacist who fathered at least four children outside of his marriage.

Just after their first son was born, his parents left him with his maternal grandparents and moved to Barranquilla, where Garcia Marquez’s father opened the first of a series of homeopathic pharmacies that would invariably fail, leaving them barely able to make ends meet.

Garcia Marquez was raised for 10 years by his grandmother and his grandfather, a retired colonel who fought in the devastating 1,000-Day War that hastened Colombia’s loss of the Panamanian isthmus.

His grandparents’ tales would provide grist for Garcia Marquez’s fiction and Aracataca became the model for Macondo, the village surrounded by banana plantations at the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountains where “One Hundred Years of Solitude” is set.

“I have often been told by the family that I started recounting things, stories and so on, almost since I was born,” Garcia Marquez once told an interviewer. “Ever since I could speak.”

Garcia Marquez’s parents continued to have children, and barely made ends meet. Their first-born son was sent to a state-run boarding school just outside Bogota where he became a star student and voracious reader, favoring Hemingway, Faulkner, Dostoevsky and Kafka.

Garcia Marquez published his first piece of fiction as a student in 1947, mailing a short story to the newspaper El Espectador after its literary editor wrote that “Colombia’s younger generation has nothing to offer in the way of good literature anymore.”

His father insisted he study law but he dropped out, bored, and dedicated himself to journalism. The pay was atrocious and Garcia Marquez recalled his mother visiting him in Bogota and commenting in horror at his bedraggled appearance that: “I thought you were a beggar.”

Garcia Marquez wrote in 1955 about a sailor, washed off the deck of a Colombian warship during a storm, who reappeared weeks later at the village church where his family was offering a Mass for his soul.

“The Story of a Shipwrecked Sailor” uncovered that the destroyer was carrying cargo, the cargo was contraband, and the vessel was overloaded. The authorities didn’t like it,” Garcia Marquez recalled.

Several months later, while he was in Europe, dictator Gustavo Rojas Pinilla’s government closed El Espectador.

In exile, he toured the Soviet-controlled east, he moved to Rome in 1955 to study cinema, a lifelong love. Then he moved to Paris, where he lived among intellectuals and artists exiled from the many Latin American dictatorships of the day.

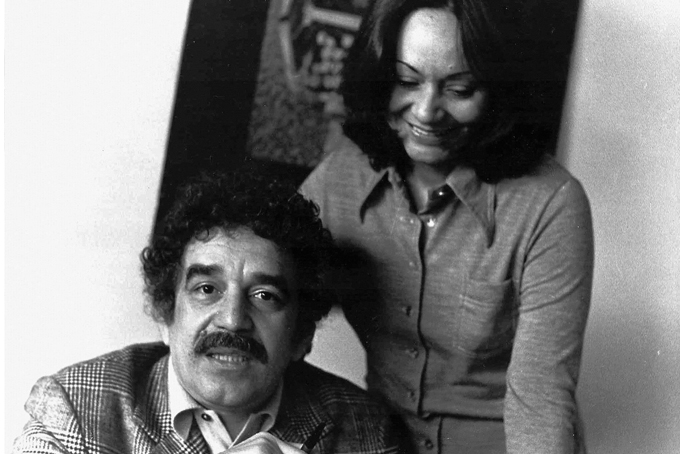

Garcia Marquez returned to Colombia in 1958 to marry Mercedes Barcha, a neighbor from childhood days. They had two sons, Rodrigo, a film director, and Gonzalo, a graphic designer.

Garcia Marquez’s writing was constantly informed by his leftist political views, themselves forged in large part by a 1928 military massacre near Aracataca of banana workers striking against the United Fruit Company, which later became Chiquita. He was also greatly influenced by the assassination two decades later of Jorge Eliecer Gaitan, a galvanizing leftist presidential candidate.

The killing would set off the “Bogotazo,” a weeklong riot that destroyed the center of Colombia’s capital and which Castro, a visiting student activist, also lived through.

Garcia Marquez would sign on to the young Cuban revolution as a journalist, working in Bogota and Havana for its news agency Prensa Latina, then later as the agency’s correspondent in New York.

Garcia Marquez wrote the epic “One Hundred Years of Solitude” in 18 months, living first off loans from friends and then by having his wife pawn their things, starting with the car and furniture.

By the time he finished writing in September 1966, their belongings had dwindled to an electric heater, a blender and a hairdryer. His wife then pawned those remaining items so that he could mail the manuscript to a publisher in Argentina.

When Garcia Marquez came home from the post office, his wife looked around and said, “We have no furniture left, we have nothing. We owe $5,000.”

She need not have worried; all 8,000 copies of the first run sold out in a week.

President Clinton himself recalled in an AP interview in 2007 reading “One Hundred Years of Solitude” while in law school and not being able to put it down, not even during classes.

“I realized this man had imagined something that seemed like a fantasy but was profoundly true and profoundly wise,” he said.

Garcia Marquez remained loyal to Castro even as other intellectuals lost patience with the Cuban leader’s intolerance for dissent. The U.S. writer Susan Sontag accused Garcia Marquez in 2005 of complicity by association in Cuban human rights violations. But others defended him, saying Garcia Marquez had persuaded Castro to help secure freedom for political prisoners.

Garcia Marquez’s politics caused the United States to deny him entry visas for years. After a 1981 run-in with Colombia’s government in which he was accused of sympathizing with M-19 rebels and sending money to a Venezuelan guerrilla group, he moved to Mexico City, where he lived most of the time for the rest of this life.

Garcia Marquez famously feuded with Peruvian author Mario Vargas Llosa, who punched Garcia Marquez in a 1976 fight outside a Mexico City movie theater. Neither man ever publicly discussed the reason for the fight.

“A great man has died, one whose works gave the literature of our language great reach and prestige,” Vargas Llosa said Thursday.

His voice shaking, face hidden behind sunglasses and a baseball cap, Vargas Llosa said Garcia Marquez’s “novels will survive him and keep gaining readers around the world.”

A bon vivant with an impish personality, Garcia Marquez was a gracious host who would animatedly recount long stories to guests, and occasionally unleash a quick temper when he felt slighted or misrepresented by the press.

Martin, the biographer, said the writer’s penchant for embellishment often extended to his recounting of stories from his own life.

From childhood on, wrote Martin, “Garcia Marquez would have trouble with other people’s questioning of his veracity.”

Garcia Marquez turned down offers of diplomatic posts and spurned attempts to draft him to run for Colombia’s presidency, though he did get involved in behind-the-scenes peace mediation efforts between Colombia’s government and leftist rebels.

In 1998, already in his 70s, Garcia Marquez fulfilled a lifelong dream, buying a majority interest in the Colombian newsmagazine Cambio with money from his Nobel award.

“I’m a journalist. I’ve always been a journalist,” he told the AP at the time. “My books couldn’t have been written if I weren’t a journalist because all the material was taken from reality.”

Before falling ill with lymphatic cancer in June 1999, the author contributed prodigiously to the magazine, including one article that denounced what he considered the unfair political persecution of Clinton for sexual adventures.

Garcia Marquez’s memory began to fail as he entered his 80s, friends said. His last book, “Memories of My Melancholy Whores,” was published in 2004.

He is survived by his wife, his two sons, Rodrigo, a film director, and Gonzalo, a graphic designer, seven brothers and sisters and one half-sister. His family said late Thursday that his remains will be cremated and a private ceremony held.

_____

Associated Press writer Frank Bajak reported from Lima, Peru. Paul Haven and Michael Weissenstein in Mexico City contributed.