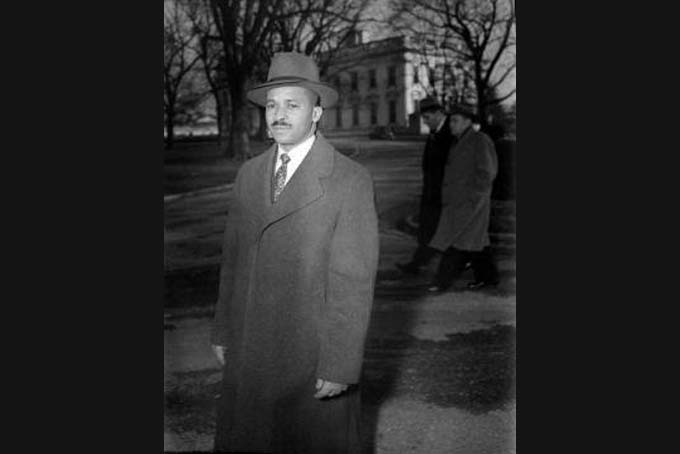

WASHINGTON (AP) — Harry McAlpin was standing outside the Oval Office, moments away from becoming the first Black reporter to attend a presidential news conference, when one of his contemporaries approached with a deal.

Stay out here, the reporter told McAlpin. The other White House correspondents would share their notes, and McAlpin would have a chance to become an official member of the correspondents association. McAlpin marched into the Oval Office anyway. Afterward, President Franklin Roosevelt shook McAlpin’s hand and said, “I’m glad to see you, McAlpin, and very happy to have you here.”

McAlpin, who became a fixture at the White House during the Roosevelt and Truman administrations, never got a White House Correspondents’ Association membership while he was alive. The rules were rigged to keep him out. But now, in its centennial year, the WHCA is honoring McAlpin with a posthumous membership and a scholarship bearing his name.

First lady Michelle Obama helped present the scholarship Saturday night during the WHCA’s annual dinner. The recipient was Glynn Hill of Philadelphia, a student at Howard University.

Also attending the dinner were McAlpin’s son Sherman, who lives in Maryland, and his family. The audience honored them with a standing ovation.

“Harry McAlpin is someone who should be recognized and shouldn’t be forgotten,” National Journal correspondent George Condon, the association’s unofficial historian, said this week during a panel discussion about diversity and the White House press corps.

WHCA President Steven Thomma noted that the correspondents group is much more diverse now than in the days when it refused membership to blacks, thus excluding them from presidential press conferences.

“Not quite where this press corps probably ought to be to have the kind of voices and questions we want to hear, but I think we’ve made some progress,” Thomma said.

Before McAlpin, minority reporters had been excluded from many official Washington news conferences.

That changed after the creation of the National Negro Publishers Association in 1941. John Sengstacke, the publisher of the Chicago Defender and one of the creators of the NNPA, opened a Washington bureau for the Defender and hired McAlpin, a lawyer, as a part-time correspondent. During a discussion with Attorney General Francis Biddle about the Black Press’ war coverage, Sengstacke suggested the attorney general ask the White House to allow a Black reporter into its news conferences.

In February 1944, Roosevelt invited 13 NNPA leaders to the White House, and three days later, McAlpin was standing outside the Oval Office, waiting for his first news conference as a White House reporter.

The breaking of that barrier did not mean that everything was now fine inside the White House for Blacks. Roosevelt press secretary Stephen Early refused to introduce McAlpin to the president, as was customary at that time, leading McAlpin to walk up to Roosevelt alone, said Earnest L. Perry Jr., who wrote about the attempt to credential a black White House correspondent for the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication.

Although he tried using his White House press pass, McAlpin was never credentialed to cover Congress. Louis Lautier ended up being the first accredited African-American congressional reporter.

McAlpin eventually left Washington to practice law in Louisville, Kentucky, and later became the president of the local NAACP chapter. He died in 1985.

___

Online:

Hear Harry S. McAlpin talk about his life at https://thisibelieve.org/essay/16794/

___

Follow Jesse J. Holland on Twitter at https://www.twitter.com/jessejholland