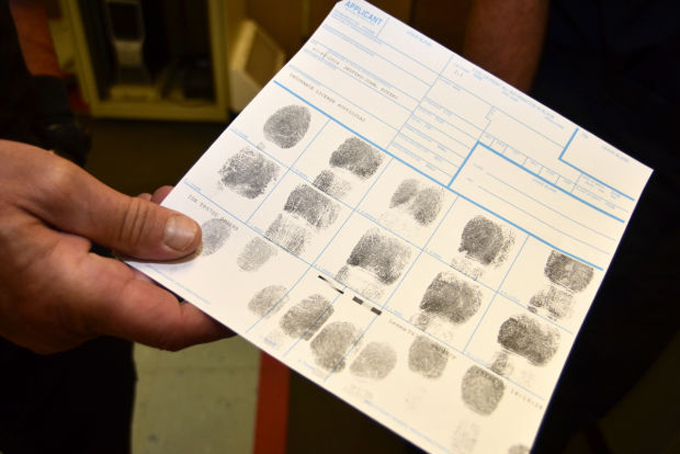

Pennsylvania police are failing to fingerprint thousands of suspects every year, jeopardizing background check systems at the state and federal levels. Lawmakers are uncertain what they can or should do about it.

A PublicSource review of data from the State Police and court system recently found that fingerprint records were missing for more than 30,000 defendants in 2013, though state law mandates that the police fingerprint suspects within 48 hours of arrest.

To talk about solutions, the House Judiciary Committee will hear testimony in Harrisburg Wednesday from a number of stakeholders, including representatives for local police, magisterial judges, the Pennsylvania Commission on Sentencing and the Pennsylvania Commission on Crime and Delinquency.

“It’s incumbent upon us to peel back the onion and find out what we need to do,” Rep. Todd Stephens (R-Montgomery), told PublicSource.

With no fingerprint, no criminal history exists in the state police database, which is used to screen gun buyers, teachers and others holding sensitive jobs involving children and the elderly.

In other words, a background check would fail to flag someone with a history of violent or sexual crimes. Criminal history would also be missing for defendants involved in crimes such as retail theft and drunk driving, meaning judges and prosecutors might not know they are dealing with repeat offenders.

Many of the lawmakers, Stephens said, may be hearing about these problems for the first time.

The hearing, is set for 10 a.m. in Room 140 of the Main Capitol before the House Judiciary Committee.

Right now, it’s unclear just who can fix the problem.

Boosting compliance could require a new law, said Stephens, who requested the hearing. It may require changes in funding. Or it may require changes inside the court system.

Mark Bergstrom, executive director of the state sentencing commission, said he favors changing the way the system works so that a court case cannot proceed if a defendant hasn’t been fingerprinted.

“It creates a mechanism for knowing each and every case is in compliance,” said Bergstrom, who is planning to testify.

He said he’s not sure whether that change can come through legislation or whether it would require a change in court procedures.

If it’s up to the court, the state’s Criminal Procedural Rules Committee would have to decide on a rule change. Then the Supreme Court would have to mandate the new protocol for state courts.

PublicSource reviewed statewide data on defendants who had been through the magisterial court system but didn’t have a fingerprint record in the State Police database. Fingerprints were missing statewide for roughly 13 percent of cases for the second half of 2013.

Many police departments do a good job of fingerprinting their defendants.

Others routinely lag.

For example, Luzerne, McKean, Lawrence and Northumberland Counties were all missing prints for roughly 40 percent of their cases, according to state figures.

Allegheny County and Philadelphia County do well on fingerprinting. Philadelphia has the best record in the state, with nearly 100 percent of criminals being fingerprinted at arrest. The Philadelphia system doesn’t allow a case to move forward unless suspects have been fingerprinted.

The state police identified missing records for about 9 percent of Allegheny County’s cases from 2013. The county has a central booking system.

John Livingood, deputy chief of the Abington

Township Police Department, said he thinks missing prints at many departments result from cases being charged by a summons.

In those cases, defendants aren’t arrested. Instead, they are served with a summons and an order to be fingerprinted on their own.

Often, the defendants don’t show up.

To fix that, Livingood said he advocates a procedural change so defendants have no choice but to be fingerprinted.

Even when a charge is delivered by a summons, police would “make every attempt to take them into custody,” said Livingood, who plans to testify.

Livingood doesn’t think a new law is necessary.

What’s needed, he said, is cooperation between magisterial courts and local police.

There are many reasons why some cases are missing fingerprints.

Police complain that fingerprinting is time consuming and that they lack resources to create local booking centers. Instead, they either wait to have prints made – often passing the buck to jailers, judges and sometimes the defendants themselves – or else go off patrol to drive a defendant elsewhere in the county to be processed.

The state is aware of these problems.

Over the past three years, the Pennsylvania Commission on Crime and Delinquency gave out $1.78 million in federal funds to educate police about the importance of fingerprinting and to help them purchase electronic fingerprinting machines.

The solution isn’t necessarily more money, Stephens said, but possibly a shift in how money is spent.

Lawmakers influence where money is directed, and one goal of the hearing is to help them learn what type of spending, legislation or procedural changes might have the greatest impact.

It could also be that the issue is out of their hands.

If the solution is a revision in court rules, then lawmakers can pass a resolution urging a change, but any action will be up to the Criminal Procedural Rules Committee and the Supreme Court.

“There may not be a legislative fix,” Stephens said.

Reach Jeffrey Benzing at 412-315-0265 or at jbenzing@publicsource.org.

Expected to testify on Wednesday, July 23, 2014:

• Linda Rosenberg, executive director, Pennsylvania Commission on Crime and Delinquency

• Mark H. Bergstrom, executive director, Pennsylvania Commission on Sentencing

• John Livingood, deputy chief, Abington Township Police Department

• Honorable Thomas G. Miller Jr., president, Special Court Judges Association of Pennsylvania and magisterial district judge, Allegheny County

• David Price, Administrative Office of Pennsylvania Courts

https://publicsource.org/node/3946