NEW YORK (AP) – The officials huddled to sort out the close call, so the TV broadcast showed the clip over and over, the announcers declaring a definite touchdown.

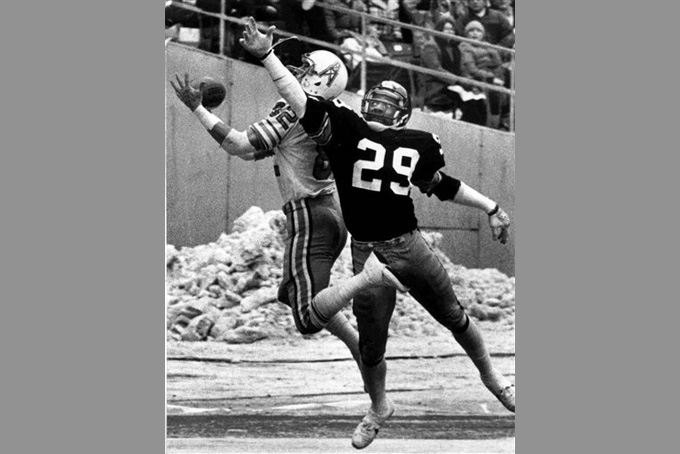

Standard fare today – but not so 35 years ago. Mike Renfro, whose lunging catch in the back of the end zone was eventually ruled incomplete, suspects that’s why so many fans remember – and rue – the play from the 1979 AFC championship game.

Viewers across America took in that moment and fumed, “It’s clear here in my den,” Renfro says.

Now fans think that at least a few times per game. Other sports joined the NFL in instituting video reviews, and viewers at home can follow along as their own replay officials.

They can watch more and better camera angles in high-definition super slow motion. Rewind the play on their DVRs. Instantly look up analysis and images on social media. Rehash the decision on 24/7 sports television.

“Officiating is better than it’s ever been,” Mike Pereira insists. “But people don’t think that.”

Pereira used to be in charge of ensuring the NFL got calls right. These days, he lets millions of fans know if a call is wrong.

After retiring as the league’s officiating chief in 2010, Pereira joined Fox in a newly created role as a rules analyst. The concept proved so popular that other networks hired their own.

“He’s become such a part of the fabric of watching the game,” says John Entz, Fox’s executive producer for NFL coverage.

Lead announcer Joe Buck used to espouse a “less is more” philosophy in analyzing questionable calls, not wanting to be burned by his lack of expertise. Then the network added what Buck calls the “the greatest gift we’ve been given”: the ability to bring in Pereira to offer an instant, definitive assessment.

Fox has leaned on him heavily on critical rulings the last two Sundays.

Pereira asserted that pass interference should have been called against the Cowboys in their wild-card win over the Lions. A week later, he correctly predicted that a Dallas catch would be overturned at Green Bay.

Buck is no Luddite when it comes to instant replay. Yet he acknowledges he went to sleep two straight Sunday nights feeling a bit conflicted about the thrilling games he had just called: The disputed officiating decisions had overshadowed everything else.

“The innocence of that is gone,” he says.

While working the baseball playoffs last fall, Buck happened to catch an old Yankees-Dodgers World Series on MLB Network. There was a close play at first base, and Buck realized he was conditioned to expect nine replays. Instead, the announcers briefly noted it was tough to tell if the runner was safe or out, then moved on.

Major League Baseball instituted video reviews for many on-field calls last season after Commissioner Bud Selig long argued human error was part of the game. The NBA has gradually expanded the scope of replay since adopting it in 2002. The NHL started reviewing goals in 1991, with ongoing discussions about widening the use of video.

The NFL first tried instant replay from 1986-91 and introduced the current system in 1999.

Those advances allow officials to get more and more calls right. They also may make fans, players and coaches less and less tolerant when mistakes are made.

“There’s more pressure than ever to get it right,” Entz says.

But some calls will always be wrong, no matter how much replay is expanded in the future.

Of the more than 40,000 plays that took place in the 2014 regular season, NFL spokesman Michael Signora says, officials were graded as correct nearly 96 percent of the time and averaged fewer than one incorrect call per game.

NBA referees are correct at a similar rate when they blow their whistles, says Rod Thorn, the league’s president of basketball operations. But when the accuracy of the calls they don’t make is factored in, the percentage dips. That’s one of many pieces of data the NBA is now tracking, to try to keep up with the ever-more-demanding expectations of fans who get to dissect slow-motion, HD replays.

“The standard has been raised because everybody sees these things now,” says Thorn, who has been involved with the league in some fashion since 1963.

Watch video of old NFL games, Pereira says, and it’s conspicuous “how many mistakes were made.” Pereira wonders if the surging popularity of the sport, not to mention the rise of gambling and fantasy football, leaves fans more invested – and accordingly more infuriated at missed calls.

Renfro agrees. He refuses to lament that instant replay wasn’t available back in January 1980. In fact, he was ambivalent about the NFL instituting it, describing himself as “old school.”

But as the game – and the money involved – got bigger, he came around to the idea. And he figures the most memorable play of his 10-year career probably had something to do with the policy.

Fans who list the non-catch as one of the most notable botched calls in NFL history may not recall this: Had the upstart Houston Oilers been awarded the touchdown against the reigning Super Bowl champion Steelers, it merely would have tied the score late in the third quarter. Pittsburgh went on to win 27-13.

What sticks in people’s minds is the loop of Renfro’s feet touching inbounds while NBC’s Dick Enberg and Merlin Olsen proclaim a touchdown.

In Sunday’s conference championship games, Pereira and CBS’s Mike Carey will be on hand for instant analysis. Pereira believes the NFL benefits from educating fans, and he’s careful to disagree with a ruling, not criticize a ref.

Still, he knows the scrutiny on each call will be relentless. For officials today, he says, “the only acceptable level of performance is perfection.”

___

AP NFL website: www.pro32.ap.org and www.twitter.com/AP_NFL