In 1968, King was planning a national occupation of Washington, D.C., to be called the Poor People’s Campaign, when he was assassinated on April 4 in Memphis. His death was followed by riots in many U.S. cities. Allegations that James Earl Ray, the man convicted of killing King, had been framed or acted in concert with government agents persisted for decades after the shooting. The jury of a 1999 civil trial found Loyd Jowers to be complicit in a conspiracy against King. The ruling has since been discredited and a sister of Jowers admitted that he had fabricated the story so he could make $300,000 from selling the story, and she in turn corroborated his story in order to get some money to pay her income tax.

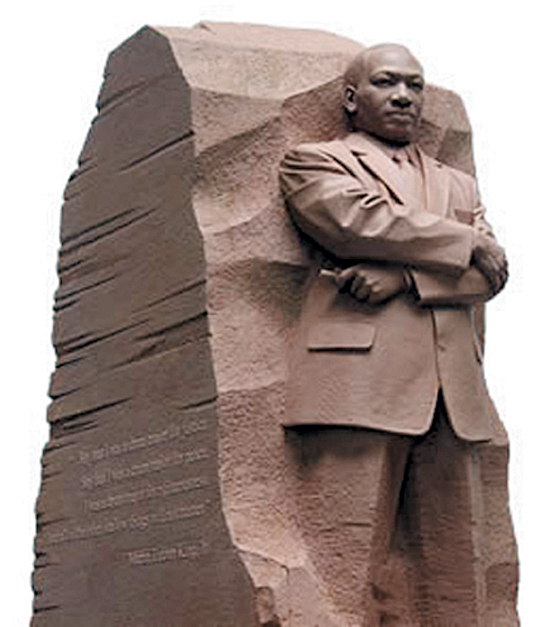

King was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom and the Congressional Gold Medal. Martin Luther King, Jr. Day was established as a holiday in numerous cities and states beginning in 1971, and as a U.S. federal holiday in 1986. Hundreds of streets in the U.S. have been renamed in his honor. In addition, a county was rededicated in his honor. A memorial statue on the National Mall was opened to the public in 2011.

King, was born on Jan. 15, 1929, in Atlanta to Rev. Martin Luther King Sr. and Alberta Williams King. King’s father, who was also born Michael King, changed his and his son’s names following a 1934 trip to Germany to attend the Fifth Baptist World Alliance Congress in Berlin. It was during this time he chose to be called Martin Luther King in honor of the German reformer Martin Luther King had Irish ancestry through his paternal great-grandfather.

Growing up in Atlanta, King attended Booker T. Washington High School. He became known for his public speaking ability and was part of the school’s debate team. King became the youngest assistant manager of a newspaper delivery station for the Atlanta Journal in 1942 at age 13. During his junior year, he won first prize in an oratorical contest sponsored by the Negro Elks Club in Dublin, Ga. Returning home to Atlanta, he and his teacher were ordered by the driver to stand so White passengers could sit down. King refused initially, but complied after his teacher informed him that he would be breaking the law if he did not go along with the order. He later characterized this incident as “the angriest I have ever been in my life.” A precocious student, he skipped both the ninth and the twelfth grades of high school. At age 15, King passed the exam and entered Morehouse. The summer before his last year at Morehouse, in 1947, an 18-year-old King made the choice to enter the ministry after he concluded the church offered the most assuring way to answer “an inner urge to serve humanity.” King’s “inner urge” had begun developing and he made peace with the Baptist Church, as he believed he would be a “rational” minister with sermons that were “a respectful force for ideas, even social protest.”

In 1948, he graduated from Morehouse with a B.A. degree in sociology, and enrolled in Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pa., from which he graduated with a B.Div. degree in 1951. King had been elected president of the student body.

King began doctoral studies in systematic theology at Boston University and received his PhD in 1955, with a dissertation on “A Comparison of the Conceptions of God in the Thinking of Paul Tillich and Henry Nelson Wieman.

King became pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Ala., when he was 25 years old, in 1954. As a Christian minister, his main influence was Jesus Christ and the Christian gospel, which he would almost always quote in his religious meetings, speeches at church and in public discourses. King’s faith was strongly based in Jesus’ commandment of loving your neighbor as yourself, loving God above all, and loving your enemies, praying for them and blessing them. His nonviolent thought was also based on the injunction to turn the other cheek in the Sermon on the Mount, and Jesus’ teaching of putting the sword back into its place (Matthew 26:52). In his famous Letter from Birmingham Jail, King urged action consistent with what he describes as Jesus’ “extremist” love, and also quoted numerous other Christian pacifist authors, which was very usual for him. In another sermon, he stated:

“Before I was a civil rights leader, I was a preacher of the Gospel. This was my first calling and it still remains my greatest commitment. You know, actually all that I do in civil rights I do because I consider it a part of my ministry. I have no other ambitions in life but to achieve excellence in the Christian ministry. I don’t plan to run for any political office. I don’t plan to do anything but remain a preacher. And what I’m doing in this struggle, along with many others, grows out of my feeling that the preacher must be concerned about the whole man.”

In his speech “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop,” he stated that he just wanted to do God’s will.

Veteran African-American civil rights activist Bayard Rustin served as King’s main advisor and mentor in the late 1950s. Rustin came from the Christian pacifist tradition; he had also studied Gandhi’s teachings and applied them with the Journey of Reconciliation campaign in the 1940s. King had initially known little about Gandhi and rarely used the term “nonviolence” during his early years of activism in the early 1950s. King also believed in and practiced self-defense, even obtaining guns in his household as a means of defense against possible attackers. Rustin guided King by showing him the alternative of nonviolent resistance, arguing that this would be a better means to accomplish his goals of civil rights than self-defense. Rustin counseled King to dedicate himself to the principles of nonviolence.

Inspired by Mahatma Gandhi‘s success with non-violent activism, King had “for a long time…wanted to take a trip to India.” With assistance from the Quaker group the American Friends Service Committee, he was able to make the journey in April 1959. The trip to India affected King, deepening his understanding of nonviolent resistance and his commitment to America’s struggle for civil rights. In a radio address made during his final evening in India, King reflected, “Since being in India, I am more convinced than ever before that the method of nonviolent resistance is the most potent weapon available to oppressed people in their struggle for justice and human dignity.”

King’s admiration of Gandhi’s nonviolence did not diminish in later years. He went so far as to hold up his example when receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, hailing the “successful precedent” of using nonviolence “in a magnificent way by Mohandas K. Gandhi to challenge the might of the British Empire…He struggled only with the weapons of truth, soul force, non-injury and courage.”

One aspect scholars haven’t dealt with for the nonviolent method of King is common sense and common knowledge of the South. Just about every Southerner had a gun and could use them and had demonstrated this many times in the past when Blacks spoke out. So if Blacks took up guns in the South they would have in most cases been eliminated quickly, and probably would have been supported by many Whites in the North. King and other activists throughout the South understood this.

As the leader of the SCLC, King maintained a policy of not publicly endorsing a U.S. political party or candidate: “I feel someone must remain in the position of non-alignment, so that he can look objectively at both parties and be the conscience of both—not the servant or master of either.” In a 1958 interview, he expressed his view that neither party was perfect, saying, “I don’t think the Republican Party is a party full of the almighty God nor is the Democratic Party. They both have weaknesses…And I’m not inextricably bound to either party.”

King critiqued both parties’ performance on promoting racial equality:

“Actually, the Negro has been betrayed by both the Republican and the Democratic party. The Democrats have betrayed him by capitulating to the whims and caprices of the Southern Dixiecrats. The Republicans have betrayed him by capitulating to the blatant hypocrisy of reactionary right wing northern Republicans. And this coalition of southern Dixiecrats and right wing reactionary northern Republicans defeats every bill and every move towards liberal legislation in the area of civil rights.”

King stated that Black Americans, as well as other disadvantaged Americans, should be compensated for historical wrongs. In an interview conducted for Playboy in 1965, he said that granting Black Americans only equality could not realistically close the economic gap between them and Whites. King said that he did not seek a full restitution of wages lost to slavery, which he believed impossible, but proposed a government compensatory program of $50 billion over ten years to all disadvantaged groups.

He posited that “the money spent would be more than amply justified by the benefits that would accrue to the nation through a spectacular decline in school dropouts, family breakups, crime rates, illegitimacy, swollen relief rolls, rioting and other social evils.” He presented this idea as an application of the common law regarding settlement of unpaid labor, but clarified that he felt that the money should not be spent exclusively on Blacks. He stated, “It should benefit the disadvantaged of all races.”

(Compiled by New Pittsburgh Courier.)