The scene

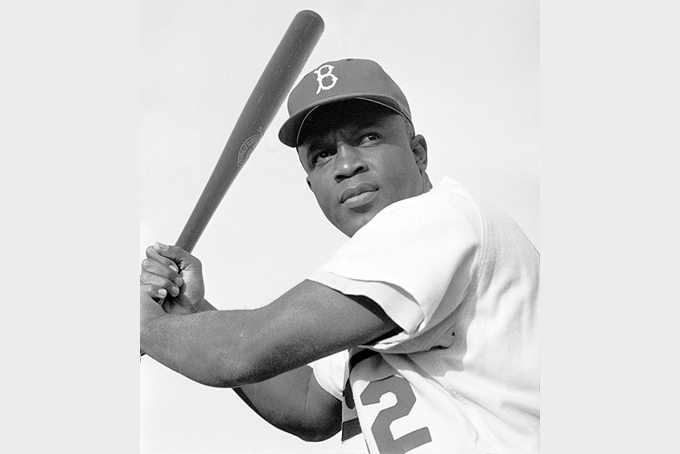

When the esteemed F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote years ago, “Show me a hero and I’ll write you a tragedy,” he most assuredly did not have Jackie Robinson in mind.

Yet when the heroic Robinson emerged from the passion play that was the integration of Major League Baseball in the spring of 1947, the feat certainly addressed the tragedy of race relations that existed in this country half a century ago…and even to this very day.

This in a country that purported that “all men are created equal, endowed with certain inalienable rights among which are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

The men

Fifty years ago the pursuit of professional baseball happiness was restricted to White men. Not since Moses Fleetwood Walker and his brother Weldly Walker made brief appearances in 1884 had the national pastime, as baseball was dubbed, seen Blacks and Whites share the same playing field. Thereafter, any men of color who aspired to play professionally had to restrict their myriad talents to the Negro Leagues, which sprouted up in the early 1900s, or travel to Mexico and other Caribbean countries to compete.

It was against this backdrop that Branch Rickey Jr., under the incessant prodding of the likes of Wendell Smith and Ric Roberts of the Pittsburgh Courier, Sam Lacy, A. S. (Doc) Young and a host of others, launched his frontal assault against the sport’s (and in a sense society’s) longstanding policy of racial segregation.

Not that he was alone among his peers in this monumental task. There is evidence that five years before baseball’s ultimate challenge began in earnest, Bill Veeck had attempted to break the game’s despicable color barrier.

As one of baseball’s most innovative owners, Veeck was viewed by the Black cognoscenti as an ally in the effort to integrate. Once Robinson was elevated to the Brooklyn Dodgers parent club, opening the doors in the National League, Veeck, then owner of the Cleveland Indians, wasted precious little time knocking open the doors in the American League, signing Larry Doby on July 5, 1947. Unlike Robinson, who apprenticed in Montreal, Doby bypassed the minors. What a shock it must have been for the shy, 22- year- old resident of Paterson, N.J., by way of South Carolina, who, at the time of his ascension to the majors, had been blitzing Negro League pitching at a .458 clip.

On the other hand, Robinson had had no such success in the Negro Leagues, according to Joe Black, who in 1952 became a teammate of Robinson’s on the legendary Dodgers teams. Fact is, Black acknowledged, the consensus among Black players at that time was that Robinson wasn’t close to being the best available player of color. Which is not to say he wasn’t the ideal person for the daunting task that lay ahead.

“I played in the Negro Leagues,” said Black in an interview conducted years ago at the Pittsburgh Courier, “and I can’t think of any Black baseball player—and that included Monte Irvin (who most thought would have been a better choice), Roy Campanella, Satchel Paige or Josh Gibson, if he had been given the chance, Willie Mays, Hank Aaron or Ernie Banks—who could have accepted the things that Jackie took and still performed on the field the way he did.

“That’s the thing: You may have been able to take it; I may have been able to say, ‘I’m not going to let them chase me out and call me all these names.’

“But bat .300, lead the league in stolen bases. That’s the thing.”

The challenge

Black continued to elaborate on his former teammate, who eventually became the first Black elected to baseball’s hallowed Hall of Fame.

“In the Negro Leagues Jackie wasn’t the best player. In fact, he was a .242 hitter, but he taught himself how to hit the curve ball in the majors, which means he had the discipline and dedication.”

But Black, who went on to become a respected executive with the Greyhound Bus Corp., was even more in awe of Robinson’s ability to handle the slings and arrows of outrageous racists, given his proclivity toward aggression.

“The strange thing is that Jackie was a violent man by nature,” Black revealed. “He loved to fight. But for some reason he accepted this challenge and kept it all inside. That’s why I say we can never thank him enough because he, more so than anyone, opened the doors and made it possible for Blacks to dominate sports as they do now.”

Furthermore, Black is convinced that it is nigh impossible for the public to properly gauge the level of abuse and torment Robinson endured in his herculean effort to make things better for those who would follow.

“People just don’t realize what he went through,” Black surmised. “A lot of times people would see him slide into second base and wipe his hand across his face and think he was wiping sweat from his brow, but he was wiping spit from his face. Some opponents didn’t try to tag him out; they just spit in his face, or stepped on his hands. The man took all kinds of things.

“We didn’t wear batting helmets back in those days,” Black added, “and they threw at his head. That’s also why he had a thick bat handle because they kept throwing balls inside on him. He adjusted by changing bats, by changing batting styles. But he accepted all of that.”

Few things irk Black more than hearing today’s young players who profess to know little or nothing of Robinson’s struggles. Or those who put forth little effort to find out about him on their own.

“Some young guys might say, ‘I’d have punched somebody if they treated me like that.’ But if Jackie had punched one person,” Black suggested, “you’d have never heard of Willie Mays or Hank Aaron because that’s what baseball was looking for after Mr. Rickey signed Jackie: one reason to stop this great experiment because it proves that you can’t mix the races.

“But Jackie never gave in to it.”

Black realizes that Robinson isn’t the only athlete of color to have sociological impact and says homage should be paid to the others just as it is paid to his former teammate.

“Jackie and Joe Louis should always have monuments in the history of Black America, even though they are athletes, because they paid the price,” said Black, a former National League Rookie of the Year.

“Joe Louis in his humble way filled Blacks with so much pride because we had a champ that we could look up to. White America could not understand why Black folks could rally around that one man. We didn’t have T.V., but when there was a (heavyweight championship) fight Black America was deserted; we were in the house listening. And Joe Louis never won, we won.

“White America tried to find a champion, and when we went to war and Joe said little things like, ‘We’re going to win because we’re on God’s side,’ even White America had to accept him as a hero.

“Then Jesse Owens did his thing at the 1936 Olympics. To me, they will always be milestones.”

Of course, Robinson’s path to immortality would not have been possible without the vision and commitment of the man respectfully and affectionately called Mr. Rickey. Despite the protestations of his fellow owners, and a hand full of Negro League bosses, Rickey stayed the course until his stated goals were fulfilled. Still, there were those who questioned the motives of the Dodgers owner.

Was he interested in correcting one of the inherent evils in his sport, in fact, in society in general? Or was the lucrative, heretofore untapped economics of Black America the driving force?

“My attitude is whether or not he did it as a humanitarian, whether he did it for mercenary reasons to make money for his ball team, the fact is he did it,” said Black. “No one else was willing to take that step. So I always say hats off to Mr. Rickey regardless of his reasons because he had the intestinal fortitude to do it.

“I know that when I was 17 years old all I wanted to be was a baseball player,” continued Black, a graduate of Morgan State, “and when they told me I couldn’t play because I was colored, I couldn’t understand how an American couldn’t play the No. 1 pastime.

“It was the first time in my life that I hated people and I hated the country because it denied me an opportunity to fulfill my dreams. Then 10 years later Mr. Rickey had the audacity to sign Jackie Robinson and here I was playing in the World Series, and that made me realize what they meant when they said America, the land of opportunity. Until then it was just words.”

Why not here?

With Pittsburgh known widely as the “capital of Black baseball,” owing to the presence of the legendary Pittsburgh Crawfords and the Homestead Grays, and under the constant needling of the Courier, one might wonder why the integration of Abner Doubleday, creation didn’t occur here.

Well according to Jules Tygiel, author of “Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy,” there were attempts to add melanin to the hapless Pirates’ lineup, half-hearted though the effort was. According to Tygiel, William Benswanger, then owner of the team, offered Josh Gibson and Buck Leonard opportunities to become Buccos, offers that met resistance from Cumberland (Cum) Posey, their boss with the Grays.

Posey reasoned that if the Pirates were permitted to pilfer his players, it wouldn’t be long before the Negro Leagues would become extinct, a prophecy that eventually became a reality.

In 1943 Roy Campanella, then of the Baltimore Elite Giants, and Dave Barnhill of the New York Cubans received letters from Benswanger inviting them to tryouts at Forbes Field, which subsequently and mysteriously were cancelled. History will show that Campanella would follow Robinson to the Dodgers and later to the Hall of Fame as one of the game’s all-time outstanding catchers. Nevertheless, one can only speculate how much the addition of Gibson, Leonard and Campanella would have helped the lowly Pirates.

In tracing the meteoric rise and fall of Black from his boyhood dreams to his realization of playing in the big leagues, one could easily surmise that it mirrored many of the early pioneers of color. He didn’t arrive in the majors until he was 28, following the itinerary that took him from the Negro Leagues to teams in Latin America to several minor league stints.

“I would get letters from teams saying if only you were White,” Black reminisced, “but I wasn’t White.”

But what he was, was a hard-throwing righthander who went on to become the first Black hurler to win a World Series game. “I tell my children that I wasn’t a superstar. I didn’t play 9-10 years but I had a dream when I was a little boy and I’m one of the few American males who can say they dreamt of playing in the big leagues and going to a World Series, and I saw it come true.

“Whether it was for one day or one year, I had it and I’m thankful for that.”

Significantly, it might have been Black’s outstanding rookie campaign that eventually led to his demise as a major leaguer. Given the success he enjoyed and the expectations that came with a guy who could throw 94-95 miles per hour, Dodgers coaches began experimenting with his style in attempts to add a wider variety of pitches to his repertoire. Eventually it led to his undoing.

“When I got to spring training they (the coaches) were going to make me a better pitcher,” Black reminisced. “They’re going to teach me the forkball and the knuckleball, but I had a problem with bending my index finger. Until that time I was just a power pitcher.

“The season starts and I begin to think maybe I’m not a good pitcher afterall. Guys who I used to get out, used to blow those kinds of guys away, now I’m sweating on guys like that and they’re pinging me to the outfield. It got so bad I used to ask Campy, ‘You tellin’ those guys what I’m going to throw?’

“It got to the point where I dreaded going out there to the mound. All my life I loved it, I wanted to go out there and play. But I didn’t want to go out there because I didn’t feel that I had the equipment. I felt like a soldier without his gun.

“It became a matter of me quitting before baseball cut me loose.”

Success; Overwhelming

Even so, Black says he realized that the Dodgers were a special breed. To such an extent that Roger Kahn immortalized them in his memorable “Boys of Summer,” the highly-acclaimed book that forever ensconced them in the American consciousness. But above all else they were winners.

“The Dodgers won because we had good players and we played as a team,” Black emphasized. “Pee Wee Reese didn’t care if he was the star, if Robinson was the star, if Campanella, if Duke Snider or if Gil Hodges was the star. Just let the Dodgers win.

“It was like one little happy family. The Dodgers all brought guys in that were handpicked. Eventually we went above the barriers of race because we were winning and because we began to learn and understand each other.”

And while admitting that harmony wasn’t always the case, with Robinson as the catalyst it certainly became an achievable end. Initially the resistance that he was forced to endure became the team’s rallying point, and a sense of accomplishment that pervaded the whole of American society.

“Like Pee Wee said at first,” Black remembered, “I didn’t want a colored guy on the team with me. But what the heck, he doesn’t play shortstop (Reese’s position) and if he’s any good he might help us win a pennant.”

“Then there was the petition started by Dixie Walker stating that he and other team members didn’t want to play with Jackie. But they noticed that he was taking all this heat and people were trying to push him out and he still kept fighting and leading them forward,” Black continued. “That earned their respect.

The Man

“So the guys stopped looking at him as Jackie Robinson the colored player and looked at him as Jackie Robinson the Dodger. Then Campy came along and did the same thing; then Don Newcombe came along and did the same thing.

“When I came along in ‘52 it was sort of expected that if the Dodgers put you on the field, they didn’t put a color on the field, they put a player on the field.”

In Black’s estimation, other teams failed to utilize that same philosophy. For the most part, they were just looking for color, hoping that they would find another Jackie Robinson. Case in point was Doby going to Cleveland, said Black.

“In the Negro Leagues Larry Doby was a second baseman but when he got to the Indians they made him an outfielder without giving him the proper preparation,” Black said. “And he took a lot of heat before finally making the adjustment.”

However, the fact remains, but for the sacrifices of Robinson it is open to speculation when Blacks would have been permitted the opportunity to perform on a Major League diamond. A great deal of homage was paid this past season to the man who made it all possible.

To paraphrase Fitzgerald, out of the tragedy of this nation’s race relations, a hero, a man for all reasons and seasons emerged. His name was Jackie Roosevelt Robinson. And the game of baseball, and America as a whole, is a lot better off because of him!

(Eddie Jefferies is the former sports editor of the New Pittsburgh Courier.)