NEW YORK (AP) _ From slave-era church outfits and Little Richard to the South Bronx and Dapper Dan the knockoff king of Harlem, the roots of hip-hop culture stretch beyond the music.

They stretch to “fresh,” that feeling when your style game is on point, just right straight out of the box. That’s the focus of a new documentary featuring Nas as an executive producer, a host of designers and some of the biggest names in music.

The film “Fresh Dressed,” out Friday in select cities and on video on demand, is the handiwork of director and journalist Sacha Jenkins, who traces the history and legacy of fresh through interviews, animation and archival footage.

“I had no idea all these things that myself and other kids in the neighborhood were doing would one day turn into this huge global industry,” the 43-year-old Jenkins said in a recent interview of his Queens upbringing.

“When I was coming up, break dancing was big and you had to have a pair of Lee twill pants. … You had to have the Le Tigre shirt, so you’re mixing and matching the preppy identity with the workwear and the athletic shoes,” he said.

And that was just Astoria.

New York City was the heartbeat of hip-hop and the style movement that accompanied its rise in the early 1970s, including distinct looks defining each of the five boroughs: velour designer sweatsuits with matching sneakers in Harlem, or a pair of Clarks on feet in Brooklyn, for example.

But fresh symbolized more than that, Jenkins said.

It was also about your “Sunday best,” a term stemming in part from laws in some states that required slave owners to buy slaves at least one decent set of clothes fit for church. It encompassed the spirit of graffiti that covered trains and walls in styles and hues borrowed to personalize jeans and denim jackets with a name down the side of a leg and original artwork on the back.

It touched young people in the gang-plagued Bronx who sewed patches, silver bangles and used cowhide stitching around the armholes of denim jackets after cutting off the sleeves, emulating the outlaw bikers in “Easy Rider.”

Or it could mean a Kangol hat, some Cazal shades, ultra-baggy pants or Adidas with fat laces that required stretching, starching and pressing to perfect the look.

Fresh prompted riots over Jordan sneakers, shootings over Marmot jackets and mass lootings at the hands of boosting crews who rushed fancy Manhattan stores in search of Polo and other coveted brands.

For rapper Big Daddy Kane of Brooklyn, it was about matching the red-and-black Gucci interior of his car to one of his custom suits.

“To me, fresh means you’re in something new, something that looks real nice … and something put together creatively,” he said by phone from Raleigh, North Carolina, where he lives.

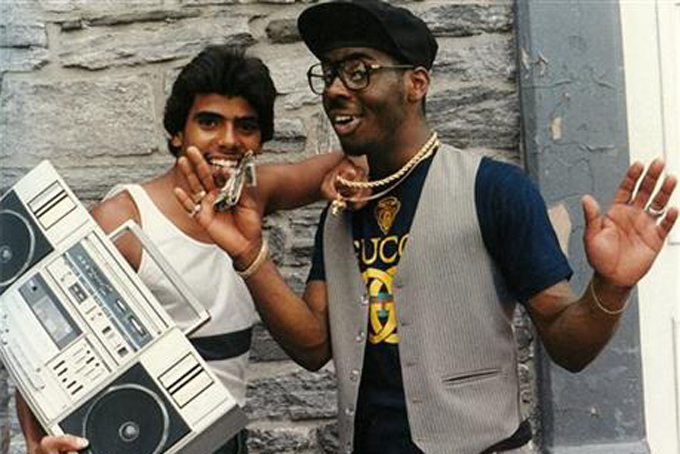

Kane, among the music pioneers to appear in “Fresh Dressed,” was once a frequenter of Daniel “Dapper Dan” Day, whose Harlem boutique made clothes to order, sometimes using famous logos like that of Louis Vuitton but done in fresh ways for up-and-coming rappers and the hustlers he counted among his urban clientele.

While Dapper Dan (squeezed out of business over alleged copyright infringement) serviced many, others in the film recalled the aspirational popularity of the real deal: Vuitton, Ralph Lauren, Tommy Hilfiger and Versace.

“A lot of the designers that people took to sometimes didn’t really want black people in their clothing, at least at that time,” Kane said.

Kane recalls his first taste of Versace, a pair of jeans.

“I remember Luther Vandross had turned me on to Versace in 1990. I remember a girl ironing the jeans for me and she was, like, `What the hell are these? What’s Vercayce?”’

Kanye West was a Lauren man from way back in Chicago. He’s now a designer himself and said it best in the film: “The entire time I grew up it was like I only wanted money so I could be fresh.”

Jenkins said the flamboyance of Little Richard as a black Liberace helped light the path in personal style for black and Latino kids with little to no money.

“Folks who didn’t have much outside of their own creativity used that creativity to express themselves in a whole new form of music and culture, and the fashion was right along with it,” he said.

There were many game changers, including Diddy. He beat out Ralph Lauren and Michael Kors to be named the Council of Fashion Designers of America’s menswear designer of the year in 2004 for his Sean John brand.

“Hip-hop culture, it had a boldness to it. You wanted everybody to know that you were down with this movement,” he said in the film.

But before that, April Walker, founder and designer of Walker Wear, remembers her fresh fashion turning point growing up. It was watching music pioneers Run-DMC onstage in matching leather suits and black hats.

“You were always taught in school dressed for success meant something else, and here they were breaking all the rules and winning,” she said in the film. “I just remember that changing my life, in the sense of everything I’d been taught was a farce to me at that point.”

It wasn’t easy for urban labels looking to compete with luxury. Most had to fight their way into stores, until the `90s opened the floodgates.

Cross Colours did about $100 million in business in 1990 with boosts from television’s “The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air” and “In Living Color.” About seven years later, the brand FUBU proved itself at $350 million.

Strides made in the `90s soon led to market saturation as hip-hop went global. Some homegrown companies had the staying power and some didn’t.

Either way, fresh lives on years after Dapper Dan’s heyday in the `80s, when the maker of one popular jacket said it would only sell him stock if he promised to rip their labels out.

“I decided to make the jackets myself,” he said in an interview, “and that’s how it all started.”

___

Follow Leanne Italie on Twitter at https://twitter.com/litalie