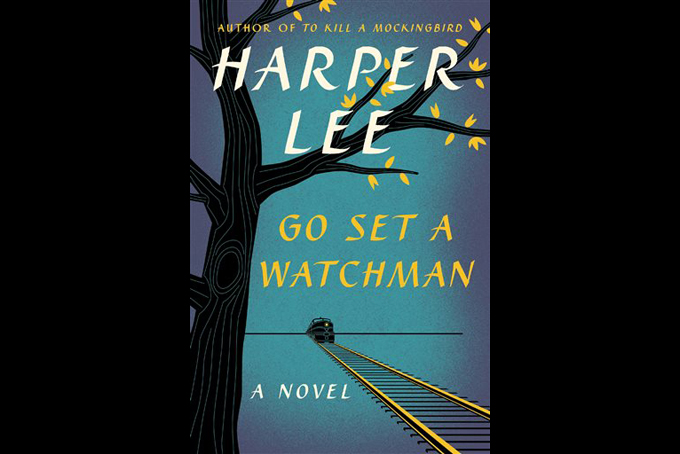

NEW YORK (AP) _ Like her classic “To Kill a Mockingbird,” the Harper Lee novel coming out next week is a coming of age story.

And not just for Scout Finch.

“Go Set a Watchman” is set in the famous fictional town of Maycomb, Alabama, in the mid-1950s, 20 years after “To Kill a Mockingbird” takes place. Scout Finch, now a grown woman known by her given name Jean Louise, is visiting from New York, unsure of whether to marry a local suitor who she has known since childhood and enduring a painful contrast between her new life and the ways of her hometown.

Scout is no longer the tomboy we know from “Mockingbird,” but has transformed from an “overalled, fractious, gun-slinging creature into a reasonable facsimile of a human being.” She is “oppressed” by Maycomb, finds it petty and provincial. And she is shaken by the response to Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark Supreme Court decision in 1954 that declared segregation in schools is “inherently unequal.”

There is nervous talk of Blacks holding public office, and marrying Whites. One prominent resident warns Scout that the court moved too quickly, that Blacks aren’t ready for full equality and the South has every right to object to interference from the NAACP and others.

“Can you blame the South for resenting being told what to do about its own people by people who have no idea of its daily problems?” he says.

That resident, to the profound dismay of his daughter, and likely to millions of “Mockingbird” readers, is Atticus Finch.

“First Woody Allen, then Bill Cosby, now Atticus Finch,” tweeted New Republic senior editor Herr Jeet, responding to early reports about the book. “You can’t trust anyone anymore.”

In “To Kill a Mockingbird,” winner of the 1961 Pulitzer Prize, Atticus risks his physical safety to defend a Black man accused of rape. He invokes the Declaration of Independence during the trial and argues for the sanctity of the legal system. Privately, he wonders why “reasonable people go stark raving mad when anything involving a Negro comes up.”

“I just hope that Jem and Scout come to me for their answers instead of listening to the town. I hope they trust me enough,” he says, referring to Jean Louise and her older brother.

In “Go Set a Watchman,” a 72-year-old Atticus laments the Supreme Court ruling and invokes the supposed horrors of Reconstruction as he imagines “state governments run by people who don’t know how to run `em.”

A tearful Scout tells the man she worshipped growing up: “You’re the only person I’ve ever fully trusted and now I’m done for.”

Lee’s attorney, Tonja Carter, said she discovered the book last year. It has been called by Amazon.com its most popular pre-order since the last Harry Potter story. Anticipating fierce resistance to the portrayal of Atticus, publisher HarperCollins issued a statement late Friday.

“The question of Atticus’s racism is one of the most important and critical elements in this novel, and it should be considered in the context of the book’s broader moral themes,” the statement reads.

“`Go Set a Watchman’ explores racism and changing attitudes in the South during the 1950s in a bold and unflinching way.”

Lee is 89, living in an assisted facility in her native Monroeville, Alabama, and has not spoken to the media in decades. In a statement issued in February, when her publisher stunned the world by announcing a second Lee novel was coming, she noted that “Watchman” was the original story.

“My editor, who was taken by the flashbacks to Scout’s childhood, persuaded me to write a novel (what became `To Kill a Mockingbird’) from the point of view of the young Scout,” she said.

HarperCollins has said “Watchman” is unaltered from Lee’s initial draft.

The current book will certainly raise questions, only some of which only Lee can answer. Why did she approve the book’s release after seemingly accepting, even welcoming, the fact that “Mockingbird” would be her only novel? How well does she remember its contents? Did her editor resist because of its political content? How autobiographical is “Watchman,” which roughly follows the path of Lee’s life in the 1950s? Does she consider the Atticus of “Watchman” more “real” than the courageous attorney of “Mockingbird”?

And how surprised should any of us be?

Atticus is hardly the only old man to fear change, or seemingly enlightened white to reveal common prejudices. Around the time Lee was working on “Watchman,” an essay by Nobel laureate William Faulkner was published in Life magazine. Faulkner had long been considered a moderate on race, praised for novels that challenged the South to confront its past. But in “A Letter to the North,” he sounds like Atticus as he considers the impact of the Supreme Court ruling.

“I have been on record as opposing the forces in my native country which would keep the condition out of which this present evil and trouble has grown. Now I must go on record as opposing the forces outside the South which would use legal or police compulsion to eradicate that evil overnight,” he wrote.

“I was against compulsory segregation. I am just as strongly against compulsory integration. … So I would say to the NAACP and all the organizations who would compel immediate and unconditional integration `Go slow now. Stop now for a time, a moment.”’

The portrait of Atticus, a supposed liberal revealing crude prejudices, will likely re-energize an old debate about “Mockingbird,” which has long been admired more by Whites than by Blacks. Widely praised as a sensitive portrait of racial tension as seen through the eyes of a child, it also has been criticized as sentimental and paternalistic.

In an interview with The Associated Press earlier this year, Nobel laureate Toni Morrison called it a “white savior” narrative, “one of those” that reduced Blacks to onlookers in their own struggles for equal rights.