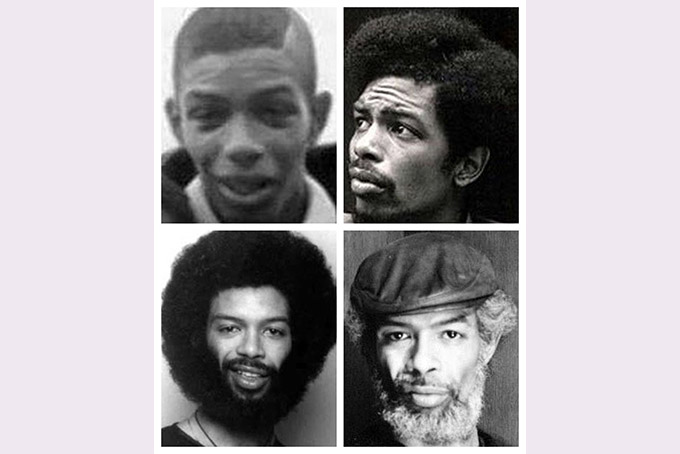

Gilbert “Gil” Scott-Heron was born April 1, 1949 in Chicago to Jamaican soccer star Giles “The Black Arrow” Heron and opera singer/teacher Robert (yes, “Robert,” as named by her father Robert), better known as Bobbie, Scott-Heron. When he was two, his parents separated after his father moved to Scotland. Immediately thereafter, Gil’s mother moved to Puerto Rico to teach. Before going, she sent him to Tennessee to live with her mother, a refined and religious woman, who was pivotal in creating the man we know of today.

Lillie, as his grandmother was called, loved gospel music. She made arrangements for him to entertain her friends by playing gospel on a broken-down piano she bought for him. And she hired a neighbor to teach him to play. By the time he was eight, he found himself attracted to what he was hearing on a local blues-oriented radio station in Memphis. Although he couldn’t really appreciate what he heard, he liked it. Accordingly, he began to mimic it on his piano — but only when grandma wasn’t around, because she was no fan of the blues.

His mother returned to New York and moved them into a Bronx apartment. But when she no longer could afford the rent there, she had to relocate them to a public housing project in the run-down Chelsea section of Manhattan.

As a sophomore at the neighborhood DeWitt Clinton High School, Gil excelled, primarily in writing courses. And one of the English teachers was so impressed that she got an interview for him at the elite Ethical Culture Fieldston School in Riverdale, a prosperous section of the Bronx. He was accepted on an academic scholarship but was disappointed to discover he was just one of five African-Americans in a class of 100.

He later enrolled at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania. He chose that school because it was where his hero Langston Hughes had attended. In fact, he actually met Langston Hughes there once. And it was at Lincoln in 1969 where he met the Last Poets and told member Abiodun Oyewole that he was so moved by their rhythmic revolutionary poetry that he “wanted to do that” in life. Although he never joined this historic spoken word and percussion group, he did begin to blossom as a musician and activist, especially when he hooked up with follow student Brian Jackson and formed the Black and Blues band. He remained at Lincoln for two years and then went on a sort of sabbatical to write two powerful and still relevant novels, The Vulture and The Nigger Factory, the former published in 1970 and the latter in 1971. In addition, he wrote a volume of poetry. And he earned a Master’s Degree in Creative Writing from Johns Hopkins University in 1972.

Music became his life when he started recording with small labels, and things expanded in 1975 when he was signed to Arista Records, making him the first artist ever on that mega-label. It was then that his Midnight Band debuted. The band’s “First Minute of a New Day” album reached Billboard’s “Top Ten Soul Album” chart. And he headlined as the musical guest on Saturday Night Live — and that was at the insistence of Richard Pryor. He toured in the early 1980s with Stevie Wonder after replacing the terminally ill Bob Marley. He also performed with the likes of Bruce Springsteen and Miles Davis.

His classic “Johannesburg,” on his 1975 “From South Africa To South Carolina” album, was the primary anti-apartheid energizing force worldwide. But he didn’t stop battling international oppression that year. In fact, when he was offered a lot of money 35 years later to perform in Tel Aviv, he was asked by pro-Palestinian activists not to support the Zionist form of apartheid which was just as evil as the South African form. He responded as expected by refusing to support Israeli racism, thereby refusing profits over principles.

Gil had become exactly what he always wanted to be: a jazzman, a soul-man, a poet, a composer, an author, and a bluesman. He also became a “bluesologist,” meaning, in his words, “a scientist who is concerned with the origin of the blues.” He listed his influences as John Coltrane, Otis Redding, Billie Holiday, Nina Simone, Huey Newton, and Malcolm X.

The drug and jail problems of Gil’s private life got more media attention than they deserved. But drugs and jail didn’t define him. They weren’t who he was permanently, only what he did temporarily. Who he was permanently was a powerful musical activist who, in a span of four decades, enlightened, activated, and entertained us with 15 studio albums, eleven compilation albums, nine live albums, and one collaboration album.

His music is vibrantly relevant today, which is why you can hear “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” “Whitey On The Moon,” “Me and The Devil,” and other classics on TV programs and in Hollywood films such as Power, Scandal, Black Lightening, Homeland, Mandela: Long Walk To Freedom, and Black Panther.

Gil became an ancestor on May 27, 2011. But he remains alive as long as his music and his message remain alive. And they both can remain alive if you support them. You can do that by purchasing his music and videos as well as especially his memoir in a book he entitled The Last Holiday, published a year after his transition. For more info, log onto gilscottherononline.com.

As said by Rumal Rackley, who’s Gil’s beloved son and estate administrator, “My responsibility is to make sure my father’s music and message are made easily available to this generation and generations to come. And it’s also to spread my father’s call to progressive activism, especially amongst young people.” Let’s help Brother/Son Rumal help Brother/Ancestor Gil do just that.