by Jay Donaldson

For New Pittsburgh Courier

Ghana, a place you just knew of which I had to return.

This was my third time visiting Ghana. I visited Ghana beginning the week of March 7, just before the coronavirus really took hold across the globe and caused shutdowns in Africa.

On my first day back, I dressed eagerly to get outside in the Ghanaian morning sun before it became a scorching heat. I saw small children and mothers walking to catch the next “Tro Tro”—oh, that’s the public transport in Ghana much like the minivans in Jamaica.

JAY DONALDSON, a Pittsburgh resident who, in 2020, made his third trip to Ghana. He’s pictured at the African Ancestral Wall.

The Tro Tros pickups are vocally preached at every stop they make, hollering their stops to the waiting passengers. It sounds like a chanting or alarm that wakes you up. If it’s your stop, you must waste no time. Get in and grab a squat, and get ready for a long, fast, bumpy ride. Seating has been altered to hold a few more passengers than normal. Seats in the aisles are what makes these Tro Tros the extra buck—a frugal way to get around in Ghana if you don’t mind being very close and uncomfortable for a few miles or more.

When Ghana’s president, Nana Akufo-Addo, ordered the country to self-quarantine, that’s when things got boring and very dangerous at the same time.

I had planned to go to Benin and Togo (nations just east of Ghana) and the Ghanaian city of Kumasi. That’s in the Ashanti region where they make the finest Kente cloths in Ghana. But it all had to be placed on hold for now. I had no choice but to be self-isolated for a period of two weeks as the president ordered.

The airports were shut down, as were restaurants, clubs, pubs, shopping malls and marketplaces. Only essential businesses were open. Luckily, before the shutdown occurred, I was able to get to PramPram and Cape Coast, both in Ghana, where I met and interviewed people.

LOCAL ASPIRING MODEL ATIHA

During the shutdown, I was happy to go to the local community roadside food stops in the Ghanaian city named Tema to get breakfast, lunch and dinner. I didn’t have much choice on what I could eat. I had a bit of a bowel problem by eating too much “Waakye,” (pronounced WAH-chay) a Ghanaian dash of rice, beans, fish or goat or beef, mixed with some veggies, spiced up with sauces and herbs, boiled egg and pasta. I ended up having to go to the pharmacy to get a laxative…

Police and soldiers were out in full force at intersections doing checks and looking at your ID. They would stop your taxi and ask where you were going, or where you were coming from. You don’t want to have a problem with the local police or soldiers. They can make your life in Ghana miserable and wish you never came here. So I tried my best to avoid the police.

THE AFRICAN ANCESTRAL WALL, IN NEW NINGO, GHANA

By the way, going for walks was now a bad idea—it could land you in custody of the police, as well. This lockdown was real. Nothing to joke about. I wanted to take pictures of the police doing checks, but if they caught me, I could have landed in a jailhouse for a long time.

It was strange going out; no vendors at the intersections, no walking sellers of goods; it was like a bad thriller movie. The scene was so silent with very little taxis and cars out and about. At the time, the virus had not gotten many Ghanaians, the few cases were mainly in the Accra area and other urban sections of the country. Villages were isolated from many people so they remained safe for the most part. Tema was about a 30-minute drive from Accra, Ghana’s most densely populated city.

There was, however, this hot spot I would fancy called Monte Carlos in “Community 10 Tema.” During the pandemic they stayed open until they were eventually ordered to close. They had a decent menu of food prepared.

I started to get concerned about my living arrangements in Tema. I was paying about 150 “Ghanaian Cedis” a night ($30 in U.S. dollars). It was “The Who Is Free” guest house. I had to find a cheaper place to live, now! The expenses were adding up. All this in the middle of a pandemic in Ghana; what else would I face on this vacation I’d embarked on?

A WOMAN FROM THE MARKETPLACE, OF WHICH THERE ARE MANY IN GHANA.

Turned out, the owner of a shop had a friend who lived in a family guest home not far from where I was staying. But the police were checking cars at main intersections leading out of town, and if you weren’t going to work or coming from work, you had to have a good excuse why you were outside during this pandemic, and I didn’t have a good excuse! Thankfully, when we were stopped, my driver explained to the officer that we were on our way to see my new place of residence in Ghana. It worked!

This new small town had everyone out working hard, doing business selling foods, pushing cars and wheelbarrows full of material. People were riding bikes, carrying heavy loads on their heads, moving swiftly, ignoring the blazing heat of the day. Later, I heard a roaring sound and felt a mighty breeze coming on stronger. It was the Atlantic Ocean and all its spacious glory, much to my delight.

We came up on Kpone (pronounced Boone), a small fishing village on the coast of the Atlantic. I thought to myself: “Well, I am in heaven.” We pulled up to the hotel/guest home, a huge, green-painted building with iron stairways. My room had a view of the ocean. The price to stay at this luscious beach house was 1,000 “Ghanaian Cedis” per month ($190 in U.S.).

During this trip to Ghana, I learned a lot about its government workings. I saw plenty of issues. One thing that had me upset was, the water situation in these small fishing villages next to the Atlantic Ocean. On many occasions, the local residents would line up for water where my building was located. I found out that water service for many residents would run out, because the pump wouldn’t bring water to some parts of where the villagers lived. It’s an antiquated and old-fashioned system that needs to be upgraded.

LOCAL ASPIRING MODEL ATIHA

From sun-up to sunset, people would line up for the free water, filling their many containers to the brim. Small children would assist in carrying the water back to the residences, to be used for bathing, cooking, washing, etc. It made me sick to see how they had to struggle in lines just to get what we in the States take for granted. Why would their leadership put their people through so much misery for clean water?

Another issue I saw were the public service systems and waste management…or lack thereof.

Ghana has some of the nicest beaches I’ve ever seen. I’d compare it with Destin, Florida, Negril in Jamaica, and Miami. But in Ghana, many of the beaches are filled with garbage coming in off the ocean. While I loved going to the beach in the mornings and sunset, it hurt me to see the plastics and other debris in the water on the sands everywhere.

BRO. NAT, ALSO KNOWN AS SIMBA, poses in front of a guest home in Kokrobite Beach, in Ghana.

The elite have a regular garbage pickup but the poor in the villages and on most coastal areas don’t have regular garbage disposals. It’s a huge problem that needs to be addressed and is becoming a biological health disaster, not just in Ghana but in most parts of Africa.

Do the leaders know anything about infrastructure? Or are they just interested in buying the latest Rolls Royce, BMW or adding another mansion to their collection? It reminds me of adults who neglect their families.

On March 6, 1957, Ghana got its independence from the UK. A very young country, indeed, but I just don’t believe there has been much attention paid to its public works departments. As a civil servant, I know what the services should be and how they must be operated.

With the airport shut down, and the borders closed, overall, I wasn’t able to move around much. We were told not to assemble in groups, couldn’t eat inside restaurants and a curfew had been instituted. Friends, my vacation was officially over. But I had to figure out some way to make the best of the situation. I began to learn the “Twi” language, a language that’s spoken by mostly everyone in southern and central Ghana. English is still the official language, though. Other languages in Ghana are Asante, Ewe, Ga, Mfantse, Kasem and more.

To my Black people in America, we have plenty to learn about our past history and forgotten languages.

JAY DONALDSON, a Pittsburgh resident who, in 2020, made his third trip to Ghana.

There’s been so much interest in us as Americans returning to the Motherland. Ghana, in particular, has injected about $1.9 billion (U.S. dollars) into its economy.

Ghana was the key transport for transporting slaves and the president of Ghana said his country felt a responsibility to welcome all those who could trace their ancestry back to Africa. I hope and pray that he realizes Blacks in America, when we do return to Ghana or any other sovereign African nation, know that we expect to work and become good citizens, and continue to the building of this very young and sometimes-inexperienced nation that we once called HOME.

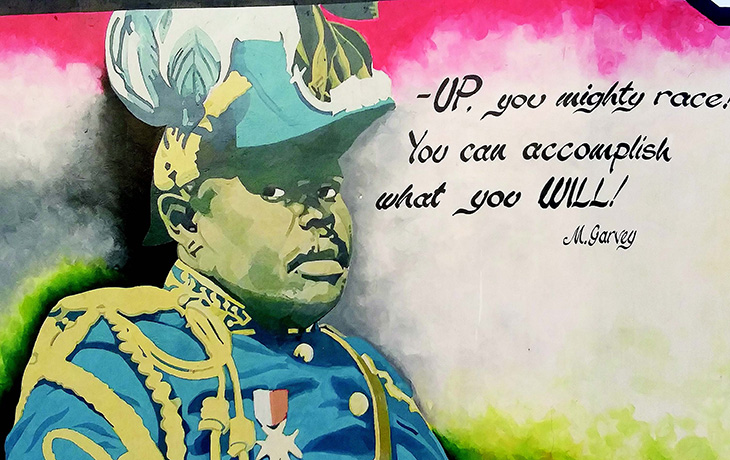

A MURAL OF MARCUS GARVEY, spotted by Jay Donaldson during his trip to Ghana from March 7 to May 16. The inspirational Garvey began the first Black nationalist movement in the U.S. and urged a “Back to Africa” movement in America. The first Ghanaian president, Kwame Nkrumah, was so fond of Garvey, that he wove Garvey’s Black Star symbolism into the nation’s identity. A black “lode star” sits in the middle of Ghana’s flag, pictured below.