by Rob Taylor Jr.

Courier Staff Writer

Sha-Asia Washington, 26 years old, from Brooklyn, New York.

Yolanda Kadima, 35 years old, from suburban Atlanta.

Both were Black women, seemingly healthy who, in July 2020, died after having an emergency C-section (Cesarean delivery).

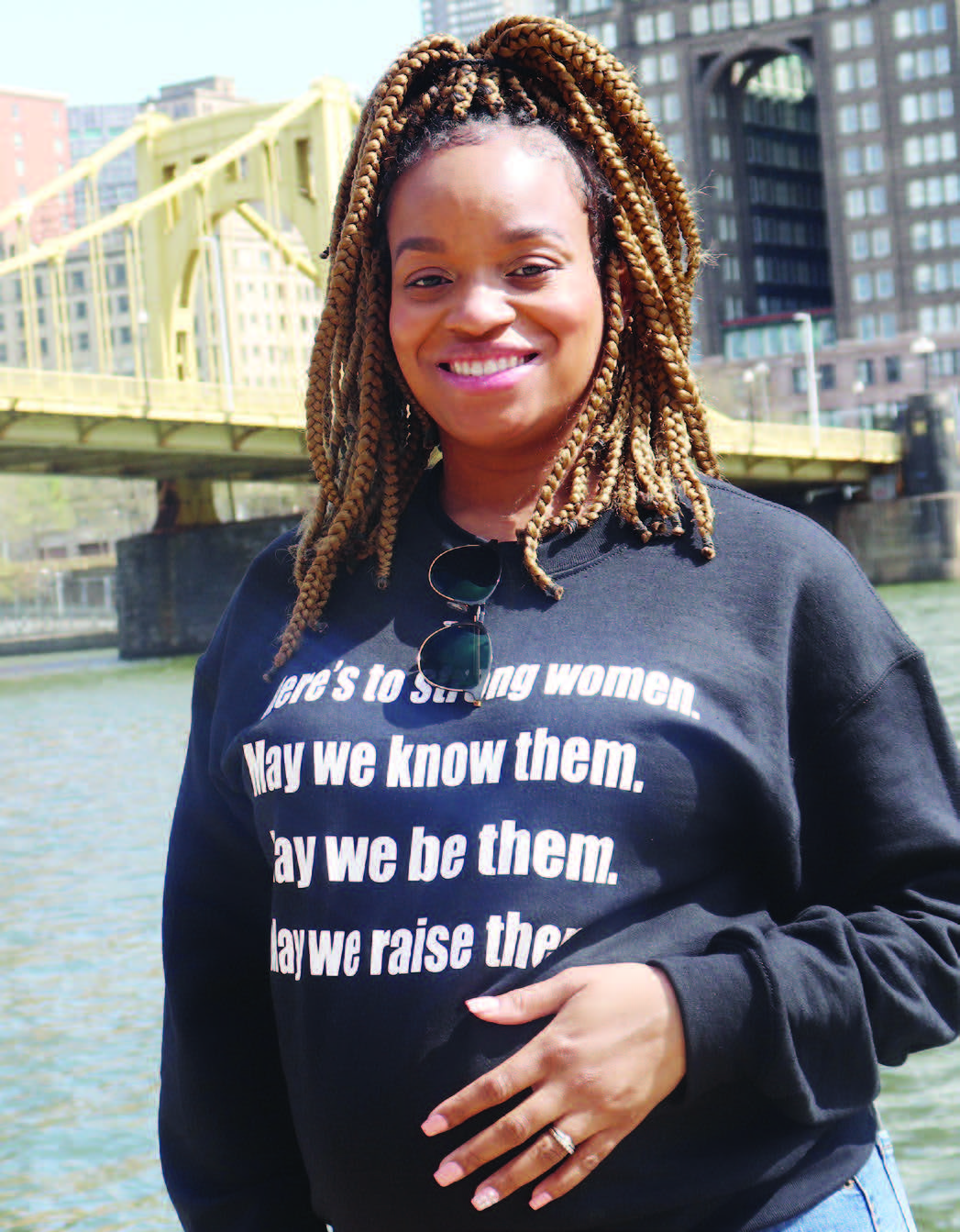

Aleta Heard, a Black woman, now 30 years old, from Pittsburgh, a graduate of Woodland Hills High School and Slippery Rock and Duquesne universities, says she’s “fortunate” to be alive today.

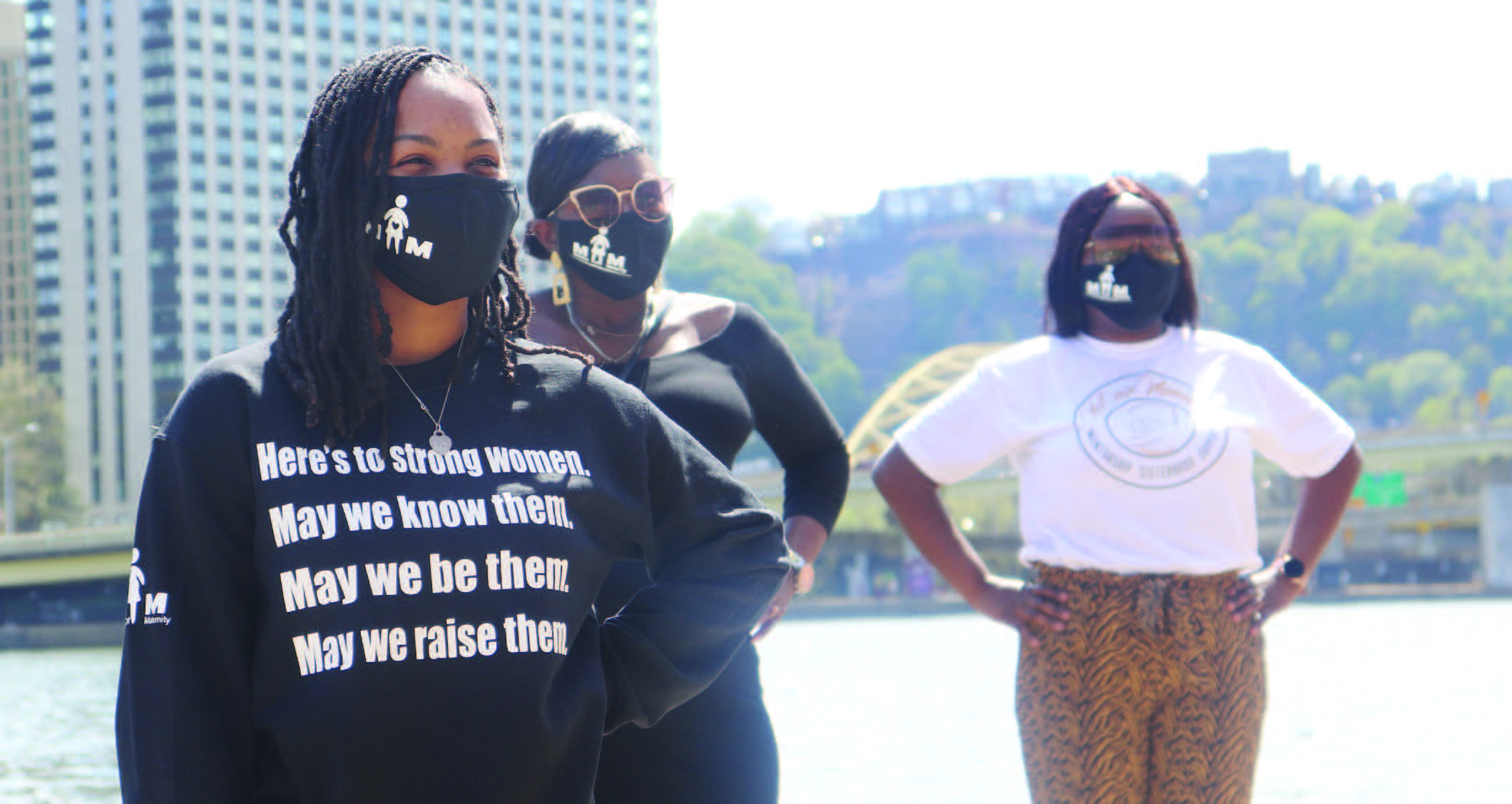

KENISHA WILSON, left, public relations specialist for “Masters of Maternity,” with Ashley Blakeman and Latrice Phoenix, who is with the organization Melanin Mommies PGH. (Photos by Rob Taylor Jr.)

She, too, had an emergency C-section while pregnant with her first child two years ago, “for reasons that I didn’t necessarily understand at the time,” she told the New Pittsburgh Courier in an exclusive interview, April 11. “I could have easily died. We (Black women) die three times more than White women while giving birth so I was very fortunate…I decided to research it more and understand the discrepancies.”

April 11-17 is

Black Maternal Health Week

Maternal mortality rates for Black women are staggering, but it’s an issue that doesn’t get a lot of attention. That’s why April 11-17 has been designated as “Black Maternal Health Week” in the U.S., now in its fourth year. It was started by the organization “Black Mamas Matter Alliance” to deepen the national conversation about Black maternal health, amplify community-driven policy, research and care solutions, provide a national platform for Black-led entities and its efforts on maternal health, and enhance community organizing on Black maternal health.

Heard took that part about “community organizing” to heart, and established “Masters of Maternity” (MOM) in March 2020, to try to unify as many Black women-led organizations in Pittsburgh who are committed to encouraging better Black maternal health.

The COVID pandemic forced Heard’s new organization to pause any in-person activities for an entire year, but on Sunday, April 11, Heard decided it was time to invite the partner organizations out to the North Shore near PNC Park for a meet-and-greet and photoshoot.

“The goal of the event is to bring our resources together and let everybody know that we stand together to solve these issues,” Heard, who is eight months pregnant, told the Courier. “We all have a common goal—we just don’t want to die, and we want to be able to have a desired birth.”

MISHA EDWARDS, right, of the Cleveland-based organization Boxmomee, speaks with Devon Taliaferro from The Midwife Center in the Strip District.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that in 2018, the Black maternal mortality rate was 37.1 (per 100,000 live births). The White maternal mortality rate was 14.7. And Black babies are twice as likely to die before their first birthday than White babies, according to the CDC.

About 700 women die each year in the U.S. due to pregnancy or delivery complications, the CDC reported. The leading causes of maternal death are heart conditions and stroke, while the CDC also pointed to hemorrhage, hyperintensive disorders of pregnancy, and infection/sepsis as other causes.

But it’s African American women that are being disproportionately affected in maternal mortality. And even if a Black woman and her child are able to live after the mother’s childbirth, Black women continue to report not knowing all the resources that could have been available to them, such as a doula or midwife.

“I wish it (support services) was around when I was giving birth to my children, and I’m probably one of the older ones here today,” said Dionna Rojas, who, along with Brandi Lee, was representing the local “Brown Mamas” organization at the April 11 event. Rojas said decades ago, “you just did what your mother did” when it came to childbirth. But with “this generation and what’s going on right now with the social justice issues, it’s very important for moms to be informed. We’re the backbones for our community…and I believe that what mom and dad does impacts our larger communities.”

ALETA HEARD, founder of “Masters of Maternity.”

A doula is defined as a “trained professional who provides continuous physical, emotional and informational support to a mother before, during and shortly after childbirth to help her achieve the healthiest, most satisfying experience possible.”

A midwife performs the same functions as a doula, but some midwives are medically trained to perform gynecological exams and deliver babies.

Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf acknowledged “Black Maternal Health Week” in an address from Harrisburg on April 12, lauding organizations like New Voices for Reproductive Justice (Pittsburgh) and Healthy Start Inc. (Pittsburgh) for their tireless work over the years. They are “doing important and innovative work to ensure the health and well-being of Black families in Pennsylvania,” Gov. Wolf said.

Why are Black women disproportionately affected by maternal mortality? Oftentimes, Black women are faced with “social inequities” that White women generally don’t face—a lack of access to healthy food choices in many Black communities, chronic health conditions, financial barriers and a tendency to be more uninsured than others outside of pregnancy, which causes prenatal care to begin later and to lose insurance coverage in the postpartum period, according to a 2017 National Public Radio report. The NPR report also said that “the hospitals where (African American mothers) give birth are often the products of historical segregation, lower in quality than those where White mothers deliver.”

ALETA HEARD, founder of “Masters of Maternity,” with her near-2-year-old daughter, Rylie. (Photos by Rob Taylor Jr.)

Then, there’s just everyday life. More researchers are finding out that the stress and discrimination that Black women face on a constant basis can contribute to problems during childbirth.

“It’s chronic stress that just happens all the time—there is never a period where there’s rest from it. It’s everywhere; it’s in the air; it’s just affecting everything,” said Fleda Mask Jackson, an Atlanta researcher who focuses on birth outcomes for middle-class Black women, in the NPR report.

“When you interview these doctors and lawyers and business executives, when you interview African American college graduates, it’s not like their lives have been a walk in the park,” said Michael Lu, a longtime disparities researcher and former head of the Maternal and Child Health Bureau of the Health Resources and Services Administration, the main federal agency funding programs for mothers and infants, in the NPR report. “It’s the experience of having to work harder than anybody else just to get equal pay and equal respect. It’s being followed around when you’re shopping at a nice store, or being stopped by the police when you’re driving in a nice neighborhood.”

Sprinkled amongst the Internet are stories of some of the many other Black women who’ve recently died during childbirth, along with the stories of those who flirted with death—like some household names, Beyonce, and Serena Williams. The two uber-celebrities, with all the money in the world, still couldn’t escape the fact that for so many Black women in the nation, “maternal mortality” is a serious topic.

BRANDI LEE AND DIONNA ROJAS, representing Brown Mamas, a local organization.

In 2018, Beyonce delivered her twins, Rumi and Sir, by emergency C-section after being bedridden for a month due to “preeclampsia,” The Washington Post reported. “‘My health and my babies’ health were in danger, so I had an emergency C-section…we spent many weeks in the NICU (Neonatal Intensive Care Unit). I was in survival mode and did not grasp it all until months later. Today I have a connection to any parent who has been through such an experience,’” recalled the R&B megastar.

Also that year, Williams, one of the greatest tennis champions of all-time, suffered a pulmonary embolism, meaning that blood clots had blocked one or more of the arteries in her lungs, The Post reported. She eventually “ripped” her C-section wound after delivering her daughter, Olympia, in that manner, and that’s when doctors discovered a large hematoma (swelling of clotted blood) in her abdomen.

Williams bluntly said afterwards that she could have died.

Some of the organizations that have partnered with Heard’s “Masters of Mortality” organization in Pittsburgh include: The Midwife Center; Brown Mamas; Healthy Start Inc.; Vibrant Pittsburgh; Jeremiah’s House; Angel’s Place; NurturePA; Melanin Mommies PGH; The MAYA Organization; and Boxmomee, which was founded by Heard’s friend from Slippery Rock University, Misha Edwards. Edwards is a Cleveland, Ohio, resident, who came down to Pittsburgh for the April 11 get-together.

“Our Black moms, we need a lot more support, we need a lot more resources,” Edwards told the Courier. “We are often forgotten.”

FEATURED IMAGE – SOME OF THE MEMBERS OF “MASTERS OF MATERNITY”—From left: Misha Edwards, Aleta Heard, Dionna Rojas, Devon Taliaferro. (Photo by Rob Taylor Jr.)