by Aubrey Bruce

For New Pittsburgh Courier

It was a hot miserable Thursday evening in mid-June. My late wife, Mamie, and I exited a cab after arriving at the now-closed CJ’s parking lot in the Strip. Mamie, who was always, shall we say, a bit “frugal,” handed the cabbie a crisp, clean one dollar bill and continued fumbling around in her purse for change. I whispered in her ear: “Please, go ahead, I’ll take care of the tip.”

Earlier that day, I had spoken with Mr. Bill Nunn and he said that he and “Mr. Ducky,” his friend since the days that fire and water were discovered, were going to the Roger Humphries jam session. Mr. Nunn asked me, “Are you going to sing?” I said yes. He said: “Well, as hot as it is, don’t forget to sing, ‘Summertime.’”

It was one of his favorites.

Bill Nunn Jr. was truly a “renaissance man.” He had a complex persona that consisted of many layers. He was truly a man of dignity and class and he inherited these traits genetically and generationally.

Bill Nunn Jr. was formally inducted into the NFL Hall of Fame during the league’s celebration weekend from Aug. 5-8. However, he was immortalized in the eyes of many African Americans long before that ceremony finally occurred. His journey toward greatness began on Sept. 30, 1924, when he was born, and ended on May 6, 2014. His father, William G. Nunn Sr., began paving “Junior’s” road to stardom when he became the managing editor of the Pittsburgh Courier during the 1940s with “Junior” closely following in his footsteps.

I was around Bill Nunn Jr. more privately than publicly than most people because privacy was the hallmark of his personality. He was a very private man that valued his privacy and if me or anyone else violated that one rule, well…see you later, alligator. One of my best stories about him was when he was one of the features writers at the Pittsburgh Courier. He was penning an anonymous roaming about town column. When certain activities were published in the Courier, the people involved could not figure out where the leaks were coming from. That was classic Bill Nunn Jr.

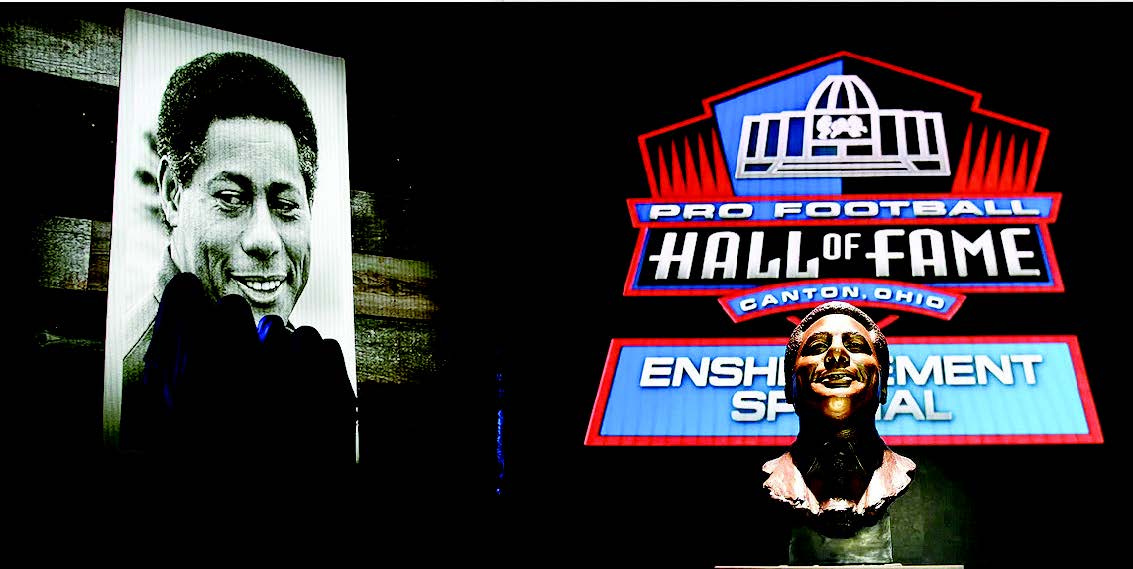

CYDNEY NUNN, granddaughter of Bill Nunn, standing next to Nunn’s bust at the Pro Football Hall of Fame ceremony on Aug. 8. “This is an incredible accomplishment, and our family is just so proud and happy that this phenomenal work that my grandfather did is finally being recognized,” Cydney said. “He was such a humble man, never one to toot his own horn. I’m glad we get to toot it for him.”

When the Pittsburgh Steelers hired him first as a part-time scout in 1967 and eventually as a full time scout in 1969, those opportunities readjusted his career “GPS” on the road toward greatness. Once I asked him how he felt being the main catalyst of Black colleges having African American players on the rosters of NFL teams. He replied: “It was the ability of the players that determined whether their college careers were going to be extended or not.”

That was classic Bill Nunn Jr.

I also asked him about any other circumstances that helped change the culture and racial makeup of the NFL. He simply said: “Sam ‘Bam’ Cunningham.” He didn’t elaborate; most of the time you had to figure it out. Bill Nunn had the luxury of finding obscure athletes at invisible colleges and put them under the glaring spotlight of the NFL, providing a chance for them to be successful. After Sam “Bam” Cunningham ran over Bear Bryant and the University of Alabama and their all-White roster in September 1970, it was not by accident that White colleges and universities began integrating at a much faster rate the following year. This, however, depleted the reservoir of talent destined to enroll and play at HBCUs.

Dan Rooney hired Bill Nunn Jr. as a trusted talent evaluator. Chuck Noll molded those players into champions and future NFL Hall-of-Famers. Donnie Shell, who was inducted into the Hall of Fame this past weekend, as well, played collegiately at South Carolina State University, a Black college. Bill Nunn knew all about him. Next thing you knew, Shell was a Steeler, a four-time Super Bowl winner, and Shell, in an interview with Steelers.com, gave credit where credit was due.

“The 1974 roster, there were 10 HBCU members and three are in the Pro Football Hall of Fame, Mel Blount (Southern), Donnie Shell, and John Stallworth (Alabama A&M). There is one gentleman who was pretty much responsible for how that went down, and that was Bill Nunn,” Shell said.

Nunn also brought Steelers L.C. Greenwood, Ernie Holmes, Dwight White, Frank Lewis and Joe Gilliam to the team. Nunn, whose titles at the Courier included sportswriter, sports editor and managing editor, would compile a list of the best players in America who played at Black colleges, called the Courier’s “Black College All-American Team.”

Simply put, no one knew the talent at Black colleges on the football field better than Bill Nunn Jr.

The legendary Steelers owner, Dan Rooney, and the legendary Steelers head coach, Chuck Noll, were deservedly honored in the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2000 and 1993, respectively. Both were alive to unveil their own busts. They did their job.

But year after year, the people that make the decisions and vote who gets into the Hall of Fame consistently fumbled the ball, because when Bill Nunn Jr. was alive, he also did his job. It’s a shame that Mr. Nunn didn’t get the chance to unveil his own bust.

But alas, as of Aug. 8, 2021, seven years after his death, we can officially say it—Bill Nunn Jr. is a member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

BILL NUNN was celebrated at the Pro Football Hall of Fame this past weekend, Aug. 5-8. A photo of his Hall of Fame bust is at right. (Photos courtesy Karl Roser/Pittsburgh Steelers)