Bos, Angie et al

by Mirya Holman, Tulane University; Angela L. Bos, The College of Wooster; J Celeste Lay, Tulane University; Jill S. Greenlee, Brandeis University, and Zoe M. Oxley, Union College

In the United States, women express less interest in politics and run for political office at lower rates than men. These gaps threaten democracy because they distort representation: Women make up 26.7% of members of Congress and 31% of state legislators, despite making up 50.8% of the population.

Imbalances like this threaten core values of representational democracy like fairness, inclusion and equality. They reduce the quality of policies produced by political bodies.

Similarly, even though women make up the majority of college students, they run for and win fewer student government positions.

Our research team has spent a lot of time studying these gaps, building on research that shows this lack of representation is associated with the fact that women are less interested in politics and less likely to run for office than men.

Organizations like Emerge America and Ready to Run tackle this problem by training women to run for public office and raising money for women candidates, even as fundraising and resource gaps persist between men and women running for office.

We asked: What if these differences in political interest and ambition start at a much earlier age?

Bos, Angie et al

Drawings help tell story

We set out to understand if gender gaps in interest appear as early as elementary school by surveying and interviewing more than 1,600 children, grades one through six.

Interviewing children about politics is a challenge. Many young children are not familiar with the political parties or terms like “Congress” or “Supreme Court.” So we developed a new tool: the Draw A Political Leader prompt.

Inspired by the “Draw a Scientist” task in research on gender gaps in STEM – science, technology, engineering and math – we asked kids to draw an image of a political leader. We asked our young respondents to tell us what the leaders in their pictures were doing and to describe the characteristics of the leader.

We also asked these children about their interest in politics and their interest in a variety of careers, including whether they would want to hold political office when they grew up.

We use these images and surveys to understand children’s process of learning both about politics and gender roles, or what scholars call “gendered political socialization.”

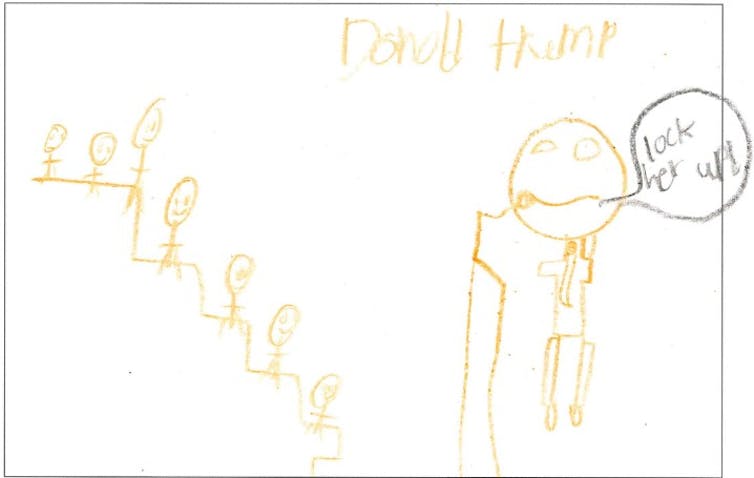

A third grade boy drew an image of Donald Trump. “He is saying a speech saying that we should lock up Hillry Clinton,” he wrote. We asked: What kinds of things do you think the leader does on a typical day? “Go on the news, go to cort.” What did he think of the leader: “A butthead.”

Bos, Angie et al

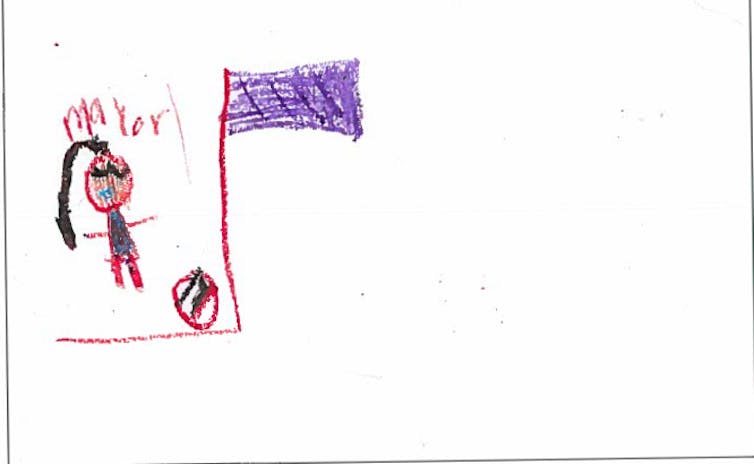

A 7-year-old girl drew the mayor, who “is talking.” And what kinds of things does she think the leader does on a typical day? “Talk talk talk doesn’t do anything else.”

Bos, Angie et al

A man’s world

As elementary-aged children observe behavior and expectations for men and women in society, they come to understand that each gender typically occupies certain roles in society, such as women working as teachers or men being firefighters.

Kids also learn about politics during this time, with lessons that often focus on key events and leaders in U.S. history – and which focus almost exclusively on men. That these two processes – learning about gender and learning about politics – occur at the same time contributes to children’s understanding that the political world is dominated by men.

Our research shows that with age, girls increasingly see political leadership as a “man’s world.” One way that we show this is by looking at the drawings that children did of what they think political leaders look like.

Three-quarters of boys draw a man when they draw a political leader, across ages. Girls, in comparison, increasingly see political leaders as men over the course of elementary school. Less than half of the youngest girls in our study – first and second graders – draw women leaders. By middle school, only about a quarter of girls draw women.

We also demonstrate that children’s exposure to politics and the likelihood of drawing a known political leader, such as Trump or Barack Obama, increase with age.

Together with the trends in gender and age in drawing political leaders, our study indicates that as young children learn about politics and political figures, they internalize the idea that politics is a man’s world.

One result of the mismatch between women’s roles and politics: Girls express lower levels of interest and ambition in politics than do boys.

As girls enter adolescence, when peers increase in influence and fitting in becomes preferred over standing out, they eschew politics. As the continuing gaps in the numbers of women in office indicate, when girls turn away from politics, many do not turn back.

[Over 115,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]

What does this mean for politics?

The roots of gender inequality in politics reach far back to childhood. Those roots take hold as a result of many factors: how kids learn about both gender roles and politics through classroom activities, how their parents discuss political events, and how the media portrays politics.

Increasing the number of women who run for and hold elected positions depends on what parents, teachers and the media present as so-called “normal” for different genders.

Mirya Holman, Associate Professor, Tulane University; Angela L. Bos, Associate Professor of Political Science and Associate Dean for Experiential Learning, The College of Wooster; J Celeste Lay, Associate Professor of Political Science, Tulane University; Jill S. Greenlee, Associate Professor of Politics and Women’s, Gender & Sexuality Studies, Brandeis University, and Zoe M. Oxley, Professor of Political Science, Union College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.