SAMUEL BLACK, WITH THE HEINZ HISTORY CENTER, SHOWS A PHOTO OF SCOTTY’S SERVICE GARAGE IN THE HILL DISTRICT. IT’S PART OF THE NEW EXHIBITION AT THE HISTORY CENTER ENTITLED, “NEGRO MOTORIST GREEN BOOK.” (PHOTO BY ROB TAYLOR JR.)

For African Americans in the mid-20th century, it was extremely dangerous to travel around this country.

That’s no joke.

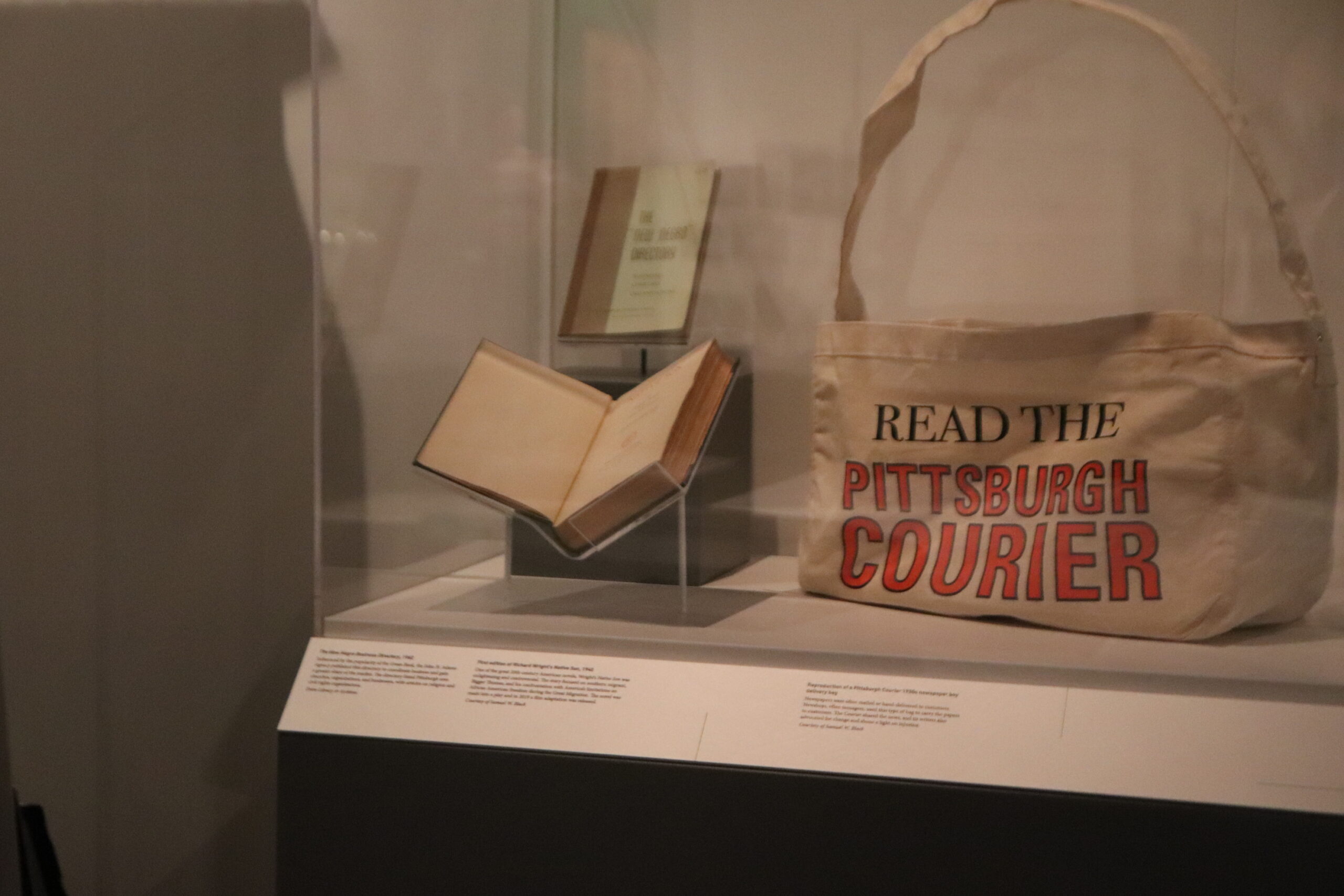

Those words are precisely what came from the mouth of Samuel Black, director of African American programs at the Heinz History Center, as he thoughtfully discussed the “Negro Motorist Green Book.” The Green Book was a publication distributed nationwide between 1936 and 1967 that provided African Americans with a directory of restaurants, gas stations, department stores and other businesses that welcomed Black travelers, during a time when segregation was the rule in the South and often accepted in the North.

Now, the Heinz History Center has unveiled Smithsonian’s Green Book exhibition for all to see and experience. Local media, including the New Pittsburgh Courier, received an advance look at the exhibition on Thursday, May 11. The exhibit will be on display until Aug. 13. Access to the exhibit is included in the general admission to the History Center.

THE PITTSBURGH COURIER OFTEN ADVERTISED THE GREEN BOOK IN ITS PRINT EDITIONS.

“It’s interesting we call it a travel guide,” voiced Heinz History Center President and CEO Andy Masich, during the media preview. “But in many ways, it’s a survival guide for African American families traveling especially in the South, but really throughout America…this guide was the survival guide that told them where it was safe.”

HEINZ HISTORY CENTER’S ANDY MASICH

The Negro Motorist Green Book was started by Victor Green, who was a postman in Harlem, New York. Near the beginning of the vast exhibit on the Heinz History Center’s first floor is a photo of Green and some artifacts from Harlem, such as a drink menu from the Harlem Casino and a cash register used at the Terrace Hall Hotel.

“He was a student of travel, student of routes,” Black said of Green. “And he was also interested in understanding the barriers African Americans faced.”

Green’s multi-faceted interests were the foundation of the annual Green Book, which grew with more businesses every year, progressing with listings from the East Coast to eventually, California.

“It was not just a publication promoting Black businesses,” Black said, “but it protected Black travelers.”

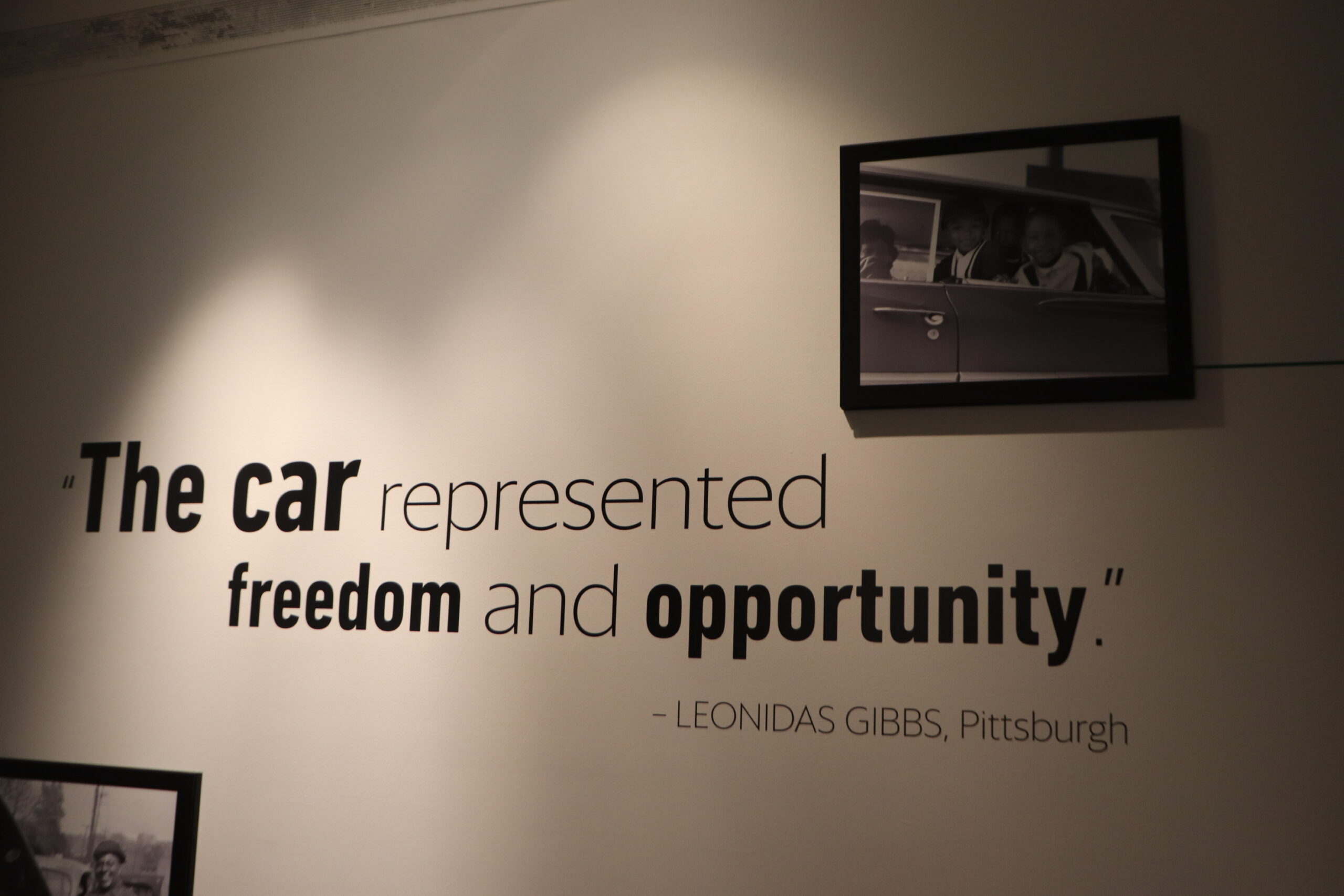

As the Negro Motorist Green Book gained in popularity, its purpose took on a even deeper meaning. The publication afforded businesses the opportunity to invite in a growing Black middle class that was interested in vacationing and traversing the country via the new craze, the automobile. There were golf courses, country clubs, national parks and other recreational landmarks included in the Green Book, signaling that those businesses wanted to be part of the betterment for Black Americans.

A PHOTO OF BLACK TRAVELERS, WHICH IS PART OF THE EXHIBIT.

“Victor Green developed a directory that addressed progressive business enterprise in the Black community that people may not have noticed before, so that’s a very important aspect,” Black noted.

A PHOTO OF BLACK TRAVELERS, WHICH IS PART OF THE EXHIBIT.

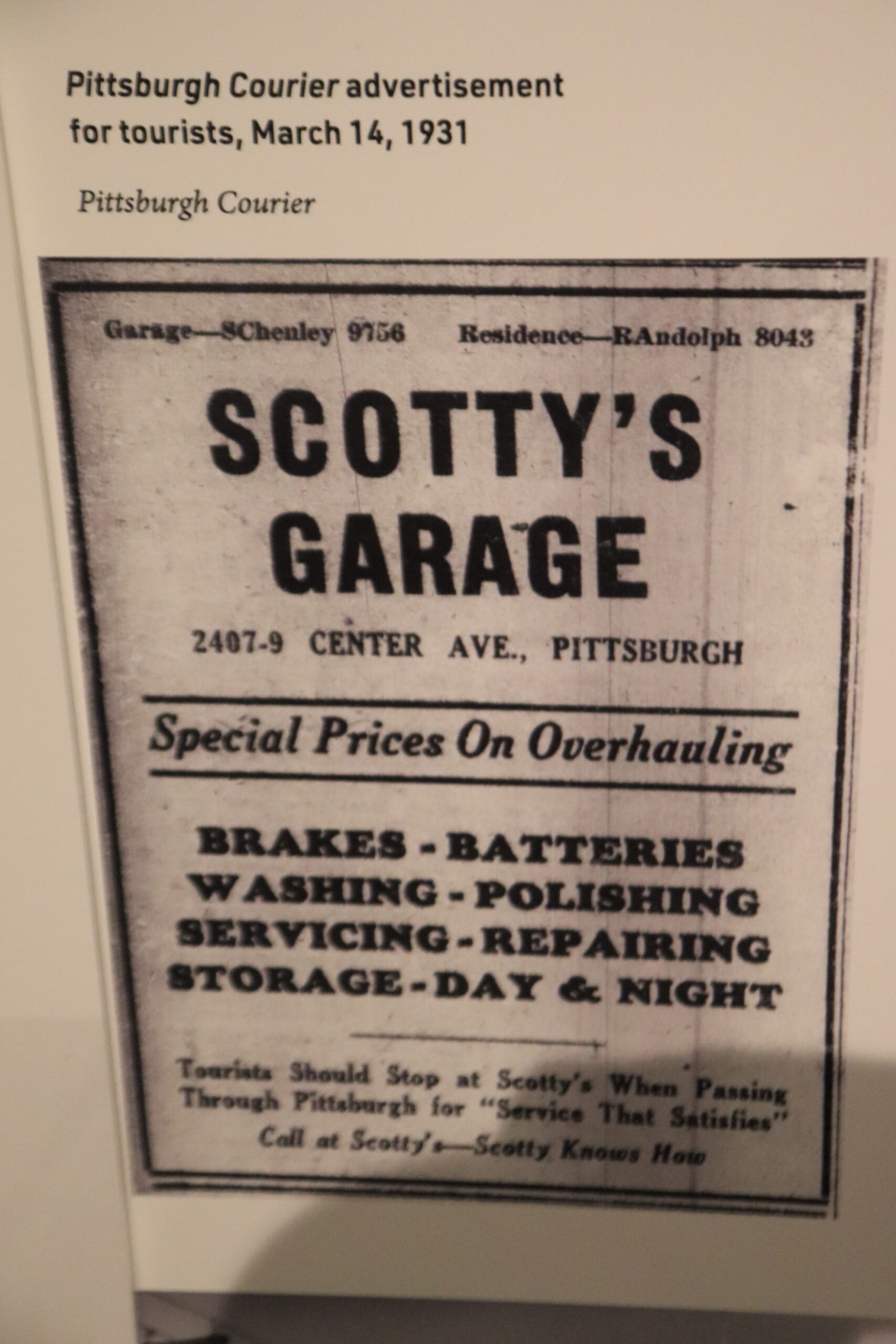

What makes the Negro Motorist Green Book exhibit at the Heinz History Center so unique is the visual display of artifacts and photos from businesses that were in the Green Book from Western Pennsylvania. More than 30 businesses were featured in the Green Book from the local area over the years, including the Flamingo Hotel (2407 Wylie Ave., 1965-1967), Agnes Taylor Tourist Home (2612 Centre Ave., 1953-1957, 1959-1962), Dearling’s Restaurant (2524 Wylie Ave., 1940-1941, 1947-1949), and Scotty’s Restaurant/Service Station (2414 Centre Ave., 1940-1941, 1947-53).

Esso service stations played a large role in Black advancement. Now known as Exxon, African Americans were welcomed with open arms at Esso. In the early 1940s, more than 300 of the 830 Esso dealers were Black. Esso had locations in Pittsburgh, two of which were owned by African Americans, which were included in the Green Book.

The Pittsburgh Courier also played a vital role in the Green Book in Pittsburgh. The Courier would advertise the Green Book in its publications, along with other competing travel guides tailored for African Americans. The Courier also promoted visits to Pittsburgh and oftentimes chronicled the travels of those who visited.

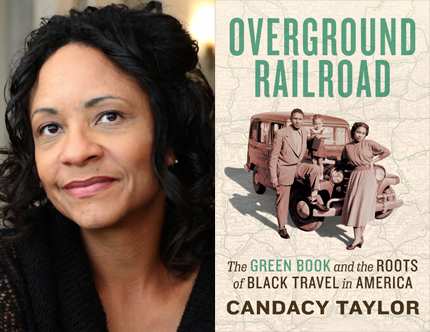

The Heinz History Center will host a few special programs for the public during the exhibit’s three-month run: “The Overground Railroad: A Conversation with (author, photographer, cultural documentarian) Candacy Taylor, hosted by former KQV reporter Elaine Effort, May 18, from 6:30-8:30 p.m.; “Crossroads of the World: the Impact of Urban Renewal Then and Now,” featuring local leaders Miracle Jones (1 Hood Media), Dr. Bonnie Young-Laing (Hill District Consensus Group), Rev. Dale B. Snyder (Bethel AME Church) and Carl Redwood Jr. (Hill District Consensus Group), June 27, from 6:30-8:30 p.m.; and “The Green Book: Guide to Freedom” film screening, July 14, 6:30-8:30 p.m.

The events on June 27 and July 14 are free with pre-registration required. The event on May 18 has tickets available for $10, $5 for History Center members.