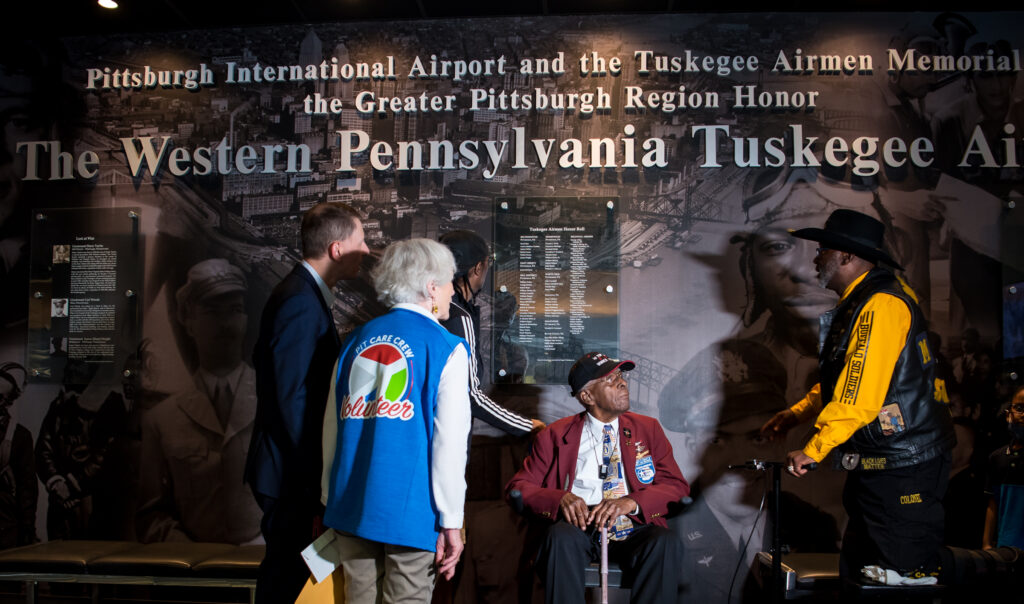

PITTSBURGH INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT’S BLUE SKY NEWS AND LOCAL MEDIA INTERVIEW LT. COL. JAMES HARVEY III, HIS FAMILY AND FRIENDS WHILE TOURING THE AIRPORT’S TUSKEGEE AIRMEN EXHIBIT ON JUNE 20. (PHOTO BY BETH HOLLERICH)

by Bob Kerlik

Blue Sky News

Lt. Col. James Harvey III smiled as he scanned the names and images of his fellow aviators at a memorial honoring the famed Tuskegee Airmen at Pittsburgh International Airport.

Harvey, who turns 100 on July 13, is one of the few remaining pilots from the famed combat aviation unit. He was honored at the airport before flying home to Denver, touring the exhibit and looking for faces he recognized.

“There’s still a lot of people who don’t know about us,” said Harvey, who was in Pittsburgh to serve as the grand marshal of the city’s Juneteenth parade. “This is a very nice display. I’ve never seen one this complete.”

Clad in a burgundy blazer adorned with patches and honors, Harvey told stories to local media, visited the airport’s USO lounge and took a window tour of the new terminal program.

He didn’t mince words when asked what younger generations should know about the Tuskegee Airmen and their role in breaking racial barriers in the U.S. military. He cited a 1925 report from the Army War College that concluded Black military members were inferior to their White counterparts and that units should be strictly segregated.

LT. COL. JAMES HARVEY III IS ONE OF THE FEW REMAINING PILOTS FROM THE FAMED COMBAT AVIATION UNIT. HE WAS HONORED AT PITTSBURGH INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT BEFORE FLYING HOME TO DENVER, TOURING THE AIRPORT’S TUSKEGEE AIRMEN EXHIBIT AND LOOKING FOR FACES HE RECOGNIZED. (PHOTO BY BETH HOLLERICH)

That report concluded that “we didn’t have the ability to do anything, so we proved them wrong,” Harvey said.

“At every turn, we proved them wrong. We were the best. They think they know us. They do not know us. We’re better than that. We proved it in our actions. Actions speak louder than words.”

Harvey was a fighter pilot with the 332nd Fighter Group’s 99th Fighter Squadron, best known as the Tuskegee Airmen, or Red Tails. He was the first Black combat jet pilot to fight in the Korean War. He was also part of a group that won the Air Force’s first Top Gun team competition in 1949, a feat that adorned his cap as he made his way through the airport.

Valerie Townsend, director of Airport Security, was among the airport staff to greet Harvey at the memorial and got her picture with him.

“I wanted to see him and meet him. He’s an important figure for Black history. He inspires Black culture,” said Townsend, who is Black. “With Black history, we didn’t learn these things in school. This is how we learn it; this is how we hear about it. Just (Harvey) being here with his daughter (at the memorial), it was refreshing to be a part of it.”

Pittsburgh is quite a distance from Tuskegee, Alabama. But it was there, at an army airfield and at nearby Tuskegee University, where thousands of Black pilots, navigators, bombardiers and support personnel were trained and formed into squadrons to fight in World War II.

The Tuskegee Airmen were the first Black aviators and military support soldiers in what was then a segregated U.S. military. According to a local historian’s research, the Pittsburgh region sent the largest contingent of Black airmen trained at Tuskegee and enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Forces during the war.

Harvey said he was happy Tuskegee Airmen and other Black military members are finally getting recognition for their service in past wars, and memorials like the one at Pittsburgh International Airport, which opened in 2013, are important.

Distinguished Flying Cross

In 1945, Harvey was an hour away from starting his journey to Europe to join the war when his group got word the war in Italy had ended.

“I didn’t get to Europe. Hitler knew I was coming,” he said, laughing. “I had my bags packed and ready to catch the train within one hour from that point. We got a message to hold us—the war in Italy was over and they expected to wind up the whole European theater, which they did the following month.

“I didn’t get to Europe, but when Korea started, I was in Japan, so I started flying missions in Korea right away.”

Harvey flew 126 missions in the Korean War and spent 22 years in the Air Force before retiring in 1965. He received the Distinguished Flying Cross for a dangerous mission in the Korean War to save endangered Army troops as he and three other jets were returning to Japan after a bomber support mission in North Korea.

“We were on our way home and we were in the Pusan area of South Korea when I got a call saying they had some Army troops pinned down, and they wanted to know if I could help. I said, ‘Sure,’” Harvey said.

“We maneuvered down to lower altitudes down in the mountains and valleys—it was cloudy—and we found the target. We emptied our guns—we had a full load of ammo, each one of us—into the enemy area and we pulled up on top of the clouds and flew back to Itazuke, Japan.

“About a week later, the commander got a telegram from the commander who was pinned down and his troops and he thanked us. For that mission, we got the Distinguished Flying Cross.”