Adobe Stock Photo

by Christine Larson, University of Colorado Boulder and Ashley Carter, University of Colorado Boulder

A major transformation is underway in Romancelandia.

Once upon a time, romance novels from major U.S. publishers featured only heterosexual couples. Today, the five biggest publishers regularly release same-sex love stories.

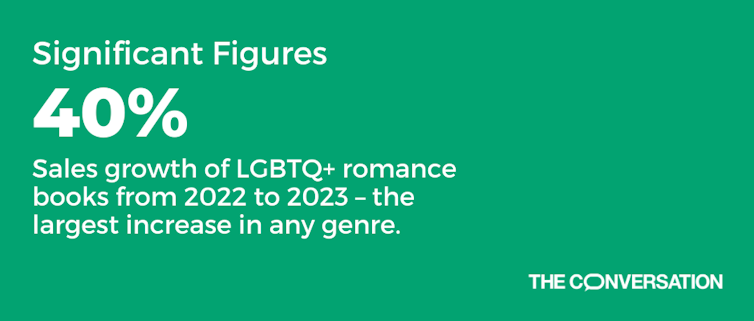

From May 2022 to May 2023, sales of LGBTQ+ romance grew by 40%, with the next biggest jump in this period occurring for general adult fiction, which grew just 17%.

The data from 2023 extends a boom that began in 2016: In the five years from May 2016 to May 2021, sales of LGBTQ+ romance grew by a jaw-dropping 740%.

It’s tempting to see this trend as a sign of the times.

After all, same-sex couples now populate TV shows, commercials and even Hallmark Christmas movies.

Surely it was only natural for books such as Casey McQuiston’s “Red, White & Royal Blue,” Lana Harper’s “Payback’s a Witch” and Cat Sebastian’s sparkling same-sex historical romance novels to eventually find their way onto bestseller lists.

But it turns out that this rise in LGBTQ+ romance was far from inevitable.

Our recent paper, based on interviews with romance editors and authors, shows that America’s biggest book publishers originally viewed LGBTQ+ romance as a niche market, tweaking their approach only after witnessing the huge success of independently published LGBTQ+ e-books.

America’s biggest book publishers originally viewed LGBTQ+ romance as a niche market.

Klaus Vedfelt/DigitalVision via Getty Images

The business of romance

Book publishing, like most of the entertainment industry, has traditionally operated under what Harvard Business School professor Anita Elberse calls the blockbuster strategy: Publishers invest huge sums into acquiring and promoting surefire bestsellers, such as Prince Harry’s “Spare,” which earned a US$20 million advance.

It’s simply more efficient for publishers to pursue a “one-to-many” business model – that is, to sell one book to a mass audience – than a “many-to-many” business model, selling a wider variety of books to many more small markets.

Historically, publishers assumed that same-sex romance would draw relatively small niche audiences, making them a riskier investment. As a result, for decades, LGBTQ+ love stories were left to small gay or lesbian presses.

Starting around 2010, however, digital romance publishing – both from self-published authors and small digital-only publishers like Ellora’s Cave and Samhain – revealed a vast, untapped appetite for more varied romance. The “Big Five” publishers – Hachette, HarperCollins, Macmillan, Penguin Random House and Simon & Schuster – realized their go-to strategy was leaving money on the table.

Richard Baker/In Pictures via Getty Images

Initially, big publishers tried to shoehorn digital romance authors into the blockbuster model by acquiring their books and issuing them in print.

That worked for E.L James’ “Fifty Shades of Grey,” which started out as fan fiction, was later released by a tiny online publisher and was eventually published by Penguin.

But for LGBTQ+ romance authors, the economics of high overhead, big print runs and a yearlong production schedule simply didn’t work for books geared for presumably smaller audience segments.

As romance readers abandoned mass-market paperbacks for a wider, fresher range of stories, romance editors at large and medium-sized publishers realized they needed to become more like digital presses.

Making love pay

How did they do this?

First, they hired new editors who had cut their teeth at tiny digital publishers with a history of releasing same-sex romance. For our paper, we interviewed several of these editors, including Sourcebooks’ Mary Altman and Angela James, founder of Harlequin’s Carina Press. Harlequin has been owned by HarperCollins since 2014.

James, formerly at Samhain, broke sacred publishing rules when she launched Carina, the first digital-only imprint at a traditional publisher. Carina lowered production and distribution costs by publishing only e-books and by offering authors higher royalties but no advances.

The lower-overhead strategy worked so well that in 2020 the imprint created Carina Adores, an e-book and print line dedicated to LGBTQ+ romance.

Altman, who had been accustomed to acquiring same-sex romance during her tenure at Ellora’s Cave, continued to do so at Sourcebooks, a mid-sized publisher partly owned by Penguin Random House. In 2020, she released the breakout LGBTQ+ bestseller “Boyfriend Material” by Alexis Hall. Sourcebooks also launched a new imprint, Bloom Books, in 2021, which sped up publishing schedules to meet the demands of self-published and other entrepreneurial authors.

These structural changes made romance imprints at large publishers nimbler, more innovative and more open to all kinds of couples.

Ironically, many of these more inclusive stories ended up appealing to mass audiences after all.

“Boyfriend Material” dominated Best Romance of the Year lists in 2020. Adriana Herrera, Alyssa Cole, K.J. Charles and dozens of other authors of LGBTQ+ romance now regularly appear on such lists. “Red White and Royal Blue” is now an Amazon Original movie.

I[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]t’s important to note that LGBTQ+ romances still represent only 4% of the print book romance market. Meanwhile, other diverse voices, including Black authors, are still underrepresented. As a whole, the Big Five publishing houses are still adhering to the blockbuster strategy. Nonetheless, the structural changes they’ve made in romance imprints have fostered an outpouring of more diverse love stories.[/perfectpullquote]

At a time when other institutions, including universities and businesses, are dismantling programs that support diversity, equity and inclusion, the LGBTQ+ romance boom serves as a reminder that inclusion doesn’t “just happen.”

Ongoing social and cultural change requires new systems, processes and structures. Absent this evolution, a host of underrepresented writers, readers and stories won’t get their happy ending.

Christine Larson, Assistant Professor of Journalism, University of Colorado Boulder and Ashley Carter, PhD Student in Journalism, University of Colorado Boulder

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.