When Duval Elementary – a school that served mostly Black and poor students in East Gainesville, Florida – failed the state’s high-stakes standardized test in 2002, district leaders pressured the school’s educators to more closely follow the curriculum.

But Gloria Jean Merriex, who taught third and fourth grade reading and fifth grade math, wasn’t interested. She argued that doing more of the same would yield more of the same results. She rebelled by creating a customized curriculum and going out of sequence, teaching the hardest units first.

Opting for a more kinetic approach to learning, she introduced music and movement. She revamped math and reading instruction by infusing the lessons with hip-hop, dance and other innovations.

And she got results, leading Duval from an F to an A in 2003 and maintaining that academic excellence until she died of a diabetic stroke in 2008. Her students achieved the greatest gains in math among all of Florida’s fifth graders.

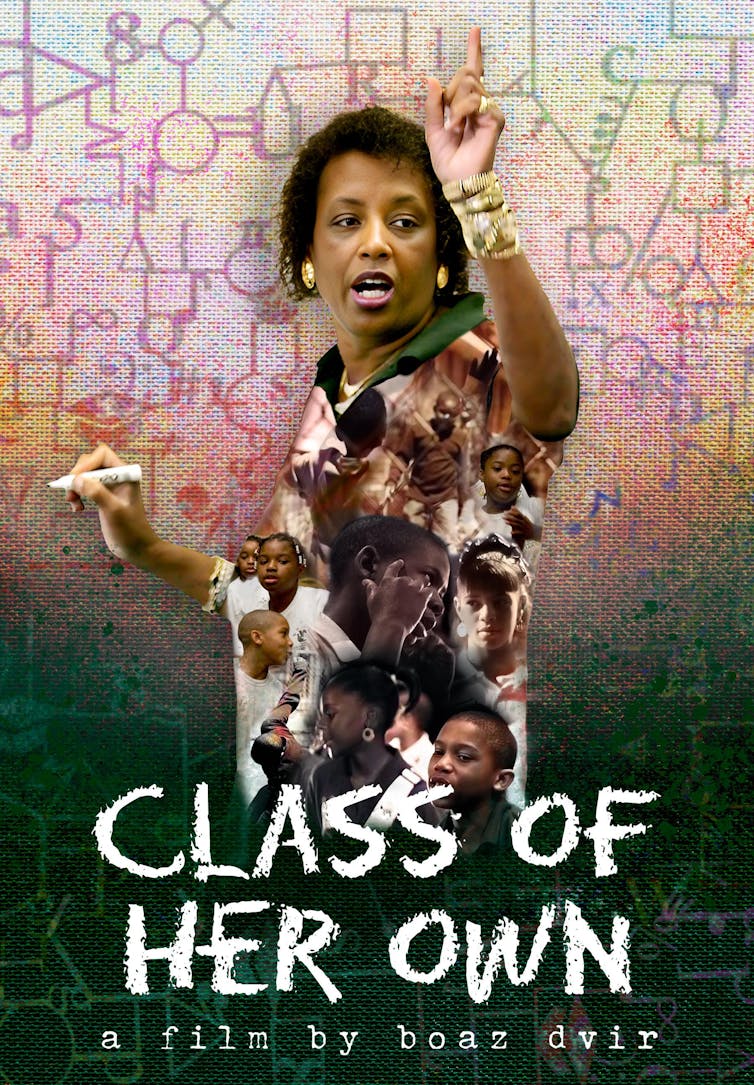

As one who has spent years researching Merriex’s career for “Class of Her Own,” a documentary set for national release on April 16, 2024, I believe the example she set could help students from economically poor families make up the considerable ground they lost during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The pandemic cost these students three-fourths of a year in math and more than a third of a year in reading, according to the Education Recovery Scoreboard, a collaboration between educational researchers at Harvard and Stanford who are examining learning loss and recovery across the country. These students suffered more than twice the pandemic-induced math skills erosion than students from families of great economic means, the scoreboard shows.

Merriex’s students consistently outscored their peers until her death at the age of 58.

Based on what I learned of her approach in the classroom, here are some of the most important takeaways from Merriex’s life and career:

1. Meet your students where they are, from where you are

Merriex breathed new life into this somewhat vague cliché by being uncompromisingly authentic. She wasn’t always that way. For much of her time at Duval, she followed the cookie-cutter curricula. But when Duval failed the Florida Comprehensive Assessment Test, she felt she’d been letting down her students all those years.

Merriex started incorporating community and cultural concepts into her curriculum.

A church choir member, she also began keeping her students on task by snapping her fingers, lighting a fire under them by turning static class exercises into dance routines and engaging them in call-and-response. In one exchange depicted in the documentary, Merriex calls out “one-fourths equal,” “two-fourths equal,” and her class responds in unison “25%,” “50%” and so on until they reach 100%.

In another, after giving an incorrect answer, one of her fifth graders says: “I made a mistake.” Merriex calls out, “It’s OK. Why?” Her students respond, “Not too many.”

It was out of this authentic stance that Merriex wrote the “Math Rap” and other hip-hop-fueled educational songs. Her teaching style exemplifies research that has found Black students learn best through “culturally relevant curriculum” and by having classroom activities connected to “prior knowledge and … real life.”

Personally, Merriex preferred other musical genres, but she knew rap would resonate with her students.

2. Make repetition a habit

Merriex turned repetition into an art. She demonstrated that saying it once means simply mentioning it; to teach, you must repeat. And, through her reverse sequencing of teaching the most challenging concepts at the outset, she gave herself plenty of chances to revisit them throughout the year.

Several domestic and international studies illustrate the benefits of repetition to a variety of students.

3. Get parents involved

Merriex believed parental involvement boosted student success – a notion that is backed up by research.

“If a kid forgot their homework, she’d get on the phone with their mom,” University of Texas at San Antonio assistant dean of research Emily Bonner says in the documentary.

To enable parents to keep up with their children, Merriex offered them evening math and reading classes. “And she sometimes used to go by their house, especially kids that are really going through a lot,” parent volunteer Anthony Guice says in the documentary.

Guice continues to share Merriex’s math and reading raps and dance routines with North Florida residents.

4. Show you care

Merriex provided free after-school tutoring and Saturday sleepover test prep at Duval. She sewed school uniforms and graduation gowns. She cooked meals. “She put us before anything, before her own health,” former student Brittany Daniels says in the documentary.

A diabetic, Merriex could ill-afford to do that. Research shows overwork can be hazardous to your health, potentially even deadly.

“She only missed three days out of 30 years of school,” her daughter, Tayana Davis, a certified nurse, says in the documentary. “That’s when she was in the hospital.”

Thus, Merriex has provided us with two lessons, one unintentionally: Care, in a multitude of ways, for your students – and yourself.

5. Embrace standardized testing

Critics have long called standardized testing inequitable and unfair. Their criticism reached a crescendo with passage of President George W. Bush’s 2001 No Child Left Behind Act, which required yearly assessments and carried consequences such as being forced to restructure or or replace staff, including the principal, for schools that didn’t make adequate yearly progress.

In recent years, states have opted for less ominous evaluations through the National Assessment of Educational Progress. Most universities have scrapped SAT and ACT requirements from their applications.

Yet Merriex, who rejected other educational mandates, welcomed Florida’s standardized test. She viewed it as an equalizing factor. She used the exam to raise expectations and motivate her students. One of the means to a bigger end, it played a part in her mission to give her students the knowledge and skills needed to succeed in school and beyond.

Recent studies show she had a point. Researchers have found a correlation between how K-12 students do on standardized tests and how they do in college. For this reason, some universities, such as Dartmouth and Yale, have reinstated the SAT and ACT.

Florida’s test certainly leveled the playing field for Merriex’s students. Their success transformed Duval from an underserved school into a well-funded magnet arts academy in 2005.

It was quite telling that after her students took Florida’s state test every spring, Merriex continued drilling its concepts through the end of the year.

The most relevant Merriex lesson, however, has nothing to do with state tests or hip-hop or chanting. “You’ve got to know who your students are, and you need to teach those students,” Bonner, the research dean from Texas, says in the documentary.

Not every group of students responds to rap or chanting, but children respond to a teacher who knows and cares about them, seeks to genuinely connect with them and unleashes their true self in the classroom to bring out the best in them.

The year after Merriex died, 2009, Duval failed the state test. The school never regained its academic footing and ultimately closed in 2015.

Boaz Dvir, Associate Professor of Journalism, Penn State

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.