Seksan Mongkhonkhamsao via Getty Images

by C. Clare Strange, Drexel University

Pennsylvania’s new sentencing guidelines went into effect on Jan. 1, 2024. They mark the eighth iteration since the state first introduced such guidelines in 1982 and are perhaps the most comprehensive revision to date.

Since Philadelphia has by far the largest share of incarcerated people in the state, the new sentencing guidelines affect many Philadelphia residents.

C. Clare Strange, an assistant research professor in the Department of Criminology and Justice Studies at Drexel University, is the principal investigator in a study that will evaluate the impacts of the new guidelines on racial and ethnic disparities in sentencing outcomes over the next five years. She spoke with The Conversation U.S. about how the guidelines have changed and what people with a criminal history in Philadelphia need to know about them.

How do judges determine a person’s sentence?

Pennsylvania uses what are known as advisory sentencing guidelines. This means that judges are required to consider what the state guidelines suggest a criminal sentence should be, but they are not required to comply with the guidelines. That’s different from other states such as Minnesota and Oregon that have mandatory sentencing guidelines. Meanwhile, a majority of U.S. states have no sentencing guidelines at all.

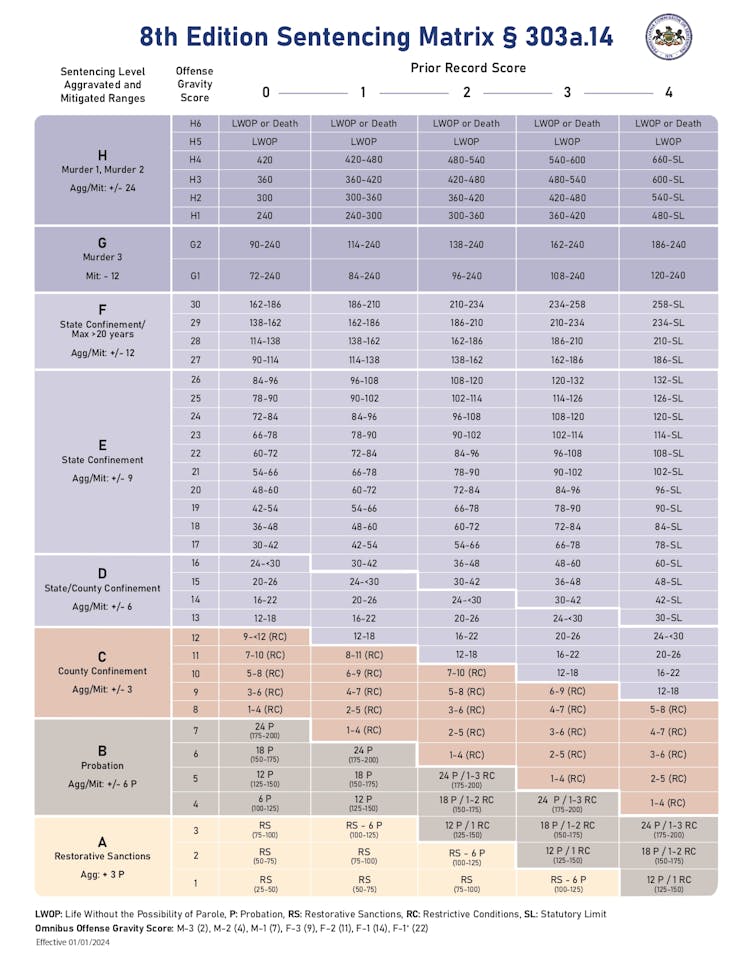

In Pennsylvania, judges primarily consider what crime the person is charged with along with their prior record or criminal history.

A matrix tells judges what the standard recommended sentencing range would be. Typically, judges sentence a defendant to a minimum term and then, after that minimum term, a parole board decides when it’s appropriate for the person to be released.

PA Commission on Sentencing

What’s new in the 2024 sentencing guidelines?

A lot has changed. Probably the most significant change is re-weighting the two categories in the matrix — offense severity and criminal history. These categories are officially known as the Offense Gravity Score and the Prior Record Score. There are now fewer categories of criminal history and far more categories of offense severity.

The revised guidelines have more than double the number of categories for Offense Gravity Score, which aim to ensure that sentences better align with crime severity. This is important because there is less opportunity for disparities to come through when a sentencing recommendation is more specific and more consistent between similar types of crimes.

Changes to Prior Record Score calculations and categories aim to address racial disparities and refocus sentence recommendations on the current offense. Lapsing policies, for example, have been expanded to reduce the impact of criminal history on sentencing for less serious offenders. These can involve the removal of specific prior offenses from inclusion in the Prior Record Score calculation after a certain amount of time has passed or after the person has had an extended crime-free period.

What’s the goal of the new guidelines?

Pennsylvania’s sentencing guideline system was mandated by the state legislature. The guidelines themselves were created by the Pennsylvania Commission on Sentencing with the the goal of promoting fair and uniform decisions on the severity of people’s punishment.

The commission was not explicitly formed to reduce punishment. That said, it has taken explicit efforts to reduce disparities in punishment that are linked to race and ethnicity.

The commission has 11 members who are appointed by the state Legislature. The members are typically judges, legislators and other criminal justice professionals. These commission members provide direction and oversight and are unique from commission staff, who collect, analyze and monitor the sentencing data for the state.

What’s been the reaction so far?

Anytime there’s talk about reducing the impact of criminal history on punishment, people express a whole spectrum of beliefs. Not everybody has the same primary concern of reducing disparities. For example, some people prefer more tough-on-crime policies. As a legislative body, the commission answers to many different constituencies.

The new guidelines mirror the federal sentencing guidelines in that there are many offense gravity categories. One critique I’ve heard is that the Offense Gravity Score now has too many categories and adjustments, and that this might complicate things such as plea negotiations.

About 95% of criminal cases are settled in plea negotiation and never go to trial. Plea negotiations are a hidden interaction where the prosecution negotiates charges and punishments with defense attorneys and their clients in exchange for a plea of guilty or no contest. Having more Offense Gravity Score categories could lead to more complicated and slower plea negotiations.

Joe Lamberti/AP

Will the guidelines reduce racial disparities in Pa.’s criminal justice system?

National statistics show that, on average, a Black person is more likely than a white person to be stopped by police, to experience police use of force when stopped, to be charged when arrested, to receive more charges when charged, to receive a harsher sentence, to be sentenced to confinement and so on. It’s a cumulative disadvantage across the justice process.

These disparities occur within Pennsylvania, too. For example, a December 2023 analysis by the Rand Corporation, a nonprofit global policy think tank, looked at racial disparities within the criminal justice system in Allegheny County, which includes Pittsburgh and is Pennsylvania’s second-most populated county after Philadelphia. It found that significant racial disparities exist at each of the key stages of people’s encounter with the criminal justice system, from having charges filed against them to having their parole revoked.

Courts to some degree inherit disparities from police and prosecutor decision making, though the new guidelines may help to reduce them at later stages, such as sentencing.

Racial and ethnic disparities in sentencing are widespread in the U.S. and are almost never entirely explained by legally relevant factors such as type of crime committed or criminal history. So researchers like me explain this leftover variation as the “race effect,” or “race and ethnicity effect.”

Part of the commission’s charge is to collect and monitor data, which can be used by the state and other criminal justice researchers. Some states may lack the infrastructure to collect or monitor data to the degree that Pennsylvania does.

That’s where my project comes in. It is designed to use commission data so that at the end of the five years we can determine whether these changes to the guidelines had the intended impact on disparities – and if they didn’t, why not.

C. Clare Strange, Assistant Research Professor of Criminology and Justice Studies, Drexel University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.