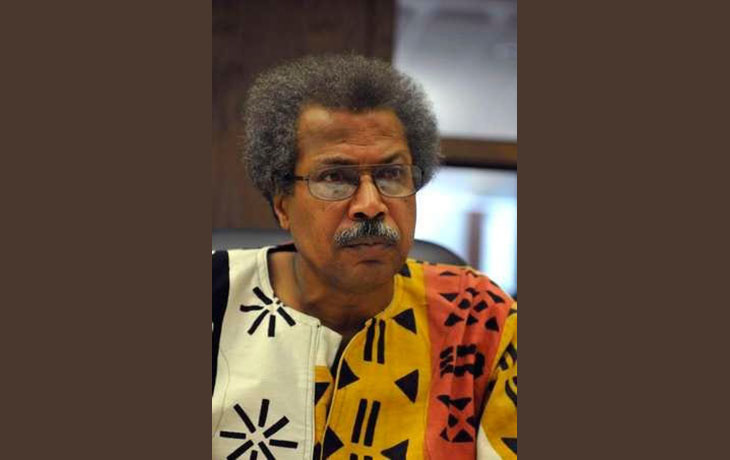

Mostafa Hefny, an Egyptian-born man who identified as Nubian, sued the United States government in 1997 to change his racial classification from White to Black.

Since the 1940s, people of North African and Middle Eastern heritage have been legally classified as White on the US census. During the turbulent and highly prejudiced decades that followed, it was to their social and economic benefit to identify as White rather than ethnic minorities.

By the 1990s, America had transformed, and being a minority had numerous benefits. Hefny’s lawsuit claimed that his White status excluded him from receiving certain minority scholarships, grants, and loans. Hefny’s case was dismissed without prejudice. In 2019, Hefny published the book I Am Not a White Man, but the US Government Forces Me to Be One. (The book also could have been titled When Being Classified as White No Longer Benefits Me.)

Recently, the Chicago Police Department changed an officer’s gender identity to match the officer’s real-life experience. Mohammad Yusuf, a Chicago police officer for the past two decades, figured the CPD would allow him to change his racial/ethnic classification from his original filing.

Yusuf identifies as both Egyptian and African American.

However, Yusuf claims that the onboarding documentation in 2004 only had three racial categories: Caucasian, Black, and Hispanic. Because he did not fit into any of the categories, Yusuf asked his supervisors which box he should choose. Someone told Yusuf to identify himself as White, and he did.

This begs the question: did he self-identify as White at the time, or did he identify as Egyptian and African American? And if he identified as Egyptian and African American, did he mark Caucasian because he thought it would be more beneficial than identifying as Black?

In 2024, when Chicago police officers are hired, they get to choose between “Black or African American,” “Hispanic or Latino,” “White,” “American Indian or Alaskan Native,” “Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander,” “two or more races,” and “I choose not to disclose.”

North African and Middle Eastern are still not included. Yusuf wanted to change his race/ethnicity to North African.

Yusuf requested that the CPD update his racial/ethnic designation on his personal file. The CPD wanted confirmation of his race/ethnicity before making the change. However, the CPD’s policy does not require transgender cops to present documentation of their transition before changing their gender on their paperwork. Apparently, this policy is consistent with mainstream medical organizations, which state that surgery is not required before officially changing one’s gender.

Yusuf took a DNA test, which confirmed his Egyptian origin. Even with DNA proof, the CPD denied his request. The CPD claimed that their policy prohibits changes in racial identity.

Yusuf filed a $1 million federal lawsuit against the City of Chicago, alleging several violations of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, failure to offer equal protection, and violations of the First Amendment.

Here is another question. Does Yusuf’s simply wish to align his racial/ethnic identity with his lived experience similar to the officer who changed their gender identity, or is this more like Hefny’s 1997 lawsuit?

According to the lawsuit, the CPD’s policy of treating racial identity as immutable defies modern understandings of race as a fluid and complex social construct. This antiquated approach fails to acknowledge the dynamic character of racial identity.

Yusuf’s attorney, Gianna Scatchell Basile, sees the action as the first of its type and a referendum on the idea of “identity-changing and fluid nature.” She added, “I think the city of Chicago was on the right track when they allowed people to change their gender identity and allowed them to identify as the proper gender.”

This is a reasonable legal argument if Yusuf simply wants to be correctly identified while executing his job, but Yusuf wishes to change his racial/ethnic heritage in order to advance professionally.

In his lawsuit, Yusuf alleged that his Caucasian categorization in his documents routinely disqualified him for advancement. Yusuf asserts that the CPD’s promotion system “particularly” advantages “minority candidates.” The lawsuit claims that despite scoring in the first promotional tier on the sergeant’s exam in 2019, Yusuf has yet to receive a promotion. Since then, there have been more than 75 merit promotions to sergeant, with “less than five” going to White candidates.

Yusef’s attorney claimed that he has no plans to retire anytime soon and that he feels professionally stuck. So it’s evident that Yusuf does not want to change his Caucasian classification to reflect his lived experience as a North African; he wants to be classified as a minority in order to avoid discrimination and get a promotion.

Too bad Yusuf chose to mark the Caucasian box when he was hired.