Former President Donald Trump, accompanied by attorney Todd Blanche, speaks to the media outside Manhattan Criminal Court on May 21, 2024. Curtis Means-Pool/Getty Images

by Jules Epstein, Temple University

After more than four weeks of often sordid testimony, accusations of lying and even a warning from Judge Juan M. Merchan to a witness to stop giving him the side-eye, lawyers in the hush-money case involving former President Donald Trump are expected to make their closing arguments on May 28, 2024.

In a jury trial, opening statements are meant to provide jurors a narrative framework to organize all the bits and pieces of evidence and testimony.

Closing arguments are not meant to simply regurgitate the testimonies of all 22 witnesses or review the roughly 200 exhibits. For both prosecutors and defense attorneys, the closing arguments serve to tell the jury why the evidence is believable or not, why and how the facts are linked or not and, most importantly, why their decision to either acquit or convict is moral and just.

Keep it simple

As a I teach law school students and practitioners, that moral message in closing arguments should link back to themes already woven into the trial.

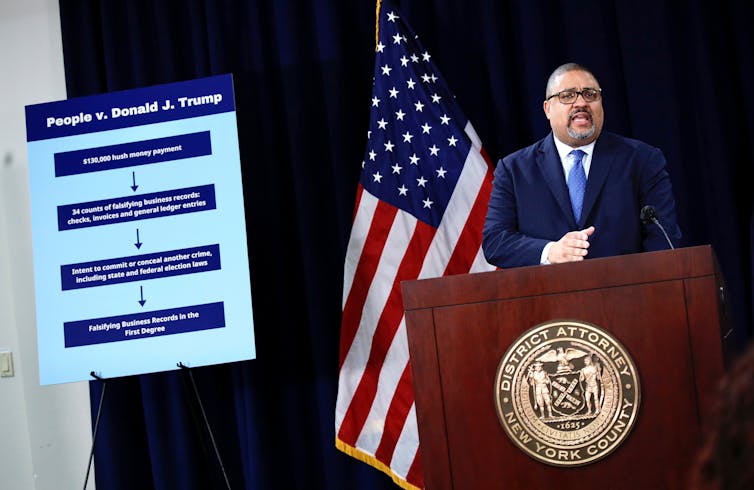

In this criminal case, one of four filed against Trump, Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg charged the former president with

34 counts of falsifying business records to hide a $130,000 payment to porn actress Stormy Daniels as part of an effort to influence voters’ knowledge about him before the 2016 presidential election.

Trump entered a plea of not guilty and did not testify.

For the prosecution, that moral message, as prosecutor Matthew Colangelo said earlier in the trial, is this: “It was election fraud, pure and simple.”

For the defense, its closing argument should include an equally direct statement, much like what Trump defense attorney Todd Blanche has said: “President Trump is innocent. President Trump did not commit any crimes. The Manhattan district attorney’s office should never have brought this case.”

There is at least one more purpose in closing arguments. It is to arm jurors with the arguments they need – either to shut down naysayers or gently persuade those in doubt – for when the real battle occurs, inside the jury room during deliberations. One way to do that is to find language from the instructions the judge will give to the jury, restate them in plain English and, in effect, make it look as if they are aligned with the judge and the law.

Less is more

A major goal of both prosecutors and defense attorneys is to untangle all of the evidence and testimony. They must cut through the distracting details and tell jurors, in effect, “Now you know why this witness was important” or “the document doesn’t lie – it shows you …”

Prosecutors in this case must focus on why Trump was involved in the alleged conspiracy and what he knew about the alleged payments.

In my experience over 45 years, the wise path is to start the closing argument with the big picture of “What did we have to prove?” and then answering in a series of bullet points that explain how they proved their case beyond a reasonable doubt.

To this end, a limited and focused use of exhibits is best – not each and every bit of evidence. Less is more also regarding salacious details, the adultery and Trump’s own vulgar words. The jury just needs the reminder – they’ll recall the details.

With star witness Michael Cohen, an attorney and Trump’s former fixer, it may be different. The prosecution can’t hide from his lies and flaws, which Trump’s defense attorneys hammered home to the jury, so it’s up to the prosecution to embrace Cohen’s failures.

Put simply, prosecutors must show that it doesn’t matter how big a liar Cohen has been in his past if, in this case, he has the receipts to back up his testimony.

A reasonable doubt?

For defense attorneys, their goal is to reassert Trump’s innocence and argue that there is plenty of reasonable doubt in the prosecution’s case.

That means pounding away at Cohen’s lack of credibility and denying that any crime was committed. If anything, they may argue, these alleged crimes were no more than bookkeeping errors that Trump didn’t know about.

But if the defense portrays everything as lies, as Trump has claimed, they may paint themselves into a corner. If the jury believes, for example, that Stormy Daniels was telling the truth when she said she had sex with Trump, then Trump’s denials may work against his lawyer’s defense strategy.

The defense has one more daunting task: to strike the balance between attacking Cohen and explaining why the lawyer Trump hired is not corroborated by the reams of evidence – and Trump’s own words.

And the defense must decide what its goal is. Is it an outright acquittal, or a hung jury in which a unanimous decision was unable to be reached?

If it is the latter, expect to have a major push on Cohen’s failings and a lack of corroboration in the hope that at least one juror will stand firm and say, “That’s just not enough.”

But the last word in these final arguments goes to the prosecutors. Because they must prove their case beyond a reasonable doubt, they will give their closing argument last and know what they have to respond to.

Jules Epstein, Professor of Law and Director of Advocacy Programs, Temple University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.