Albert Johnson, aka Prodigy, (left) and Kejuan Muchita, aka Havock, of the hip hop duo Mobb Deep in New York in 2006. Johnson died on June 20, 2017 in Las Vegas, Nev. (AP Photo/Jim Cooper)

by Marcus Evans, McMaster University

In June 2017, Albert “Prodigy” Johnson passed away due to sickle cell anemia. He was one half of Mobb Deep, a New York City hip-hop duo whose 1995 song, “Shook Ones, Pt. II” drew some attention from the 2002 film 8 Mile.

Approaching the seventh anniversary of Prodigy’s death, I hope to convey my own interpretation of his lived experience through a retelling of the myth by which he lived.

As a scholar of religion who examines race, religion and myth in the urban arts, I understand myth as metaphors, archetypes and stories by which people make sense of their lives. Myth also encompasses the person’s lifeworld itself, as it becomes enchanted by such mythic qualities.

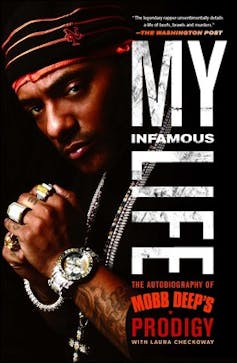

For me, Prodigy’s 2012 autobiography, My Infamous Life, in dialogue with his music and creative choices, suggests he saw himself as living in a world of conflicting forces, particularly positive versus negative or good versus evil.

Prodigy’s autobiography, ‘My Infamous Life.’ (Simon & Schuster)

‘Fallen angel’

In his autobiography, for instance, Prodigy likened himself to a “fallen angel,” someone who knows what is good but succumbed to doing evil. He embodied this myth by tattooing a half demon-half angel on his back.

Prodigy wrote that for nearly all his life he had been “straddling the fence” between “good” and “evil.”

But after serving more than three years in prison between 2007 and 2011, he decided to fully align himself to the side of the “good.”

‘Hell on Earth’

Prodigy explained that around the time of Mobb Deep’s third album, Hell on Earth (1996), “a spiritual war was going on within me.” He wanted to live a positive life, but his environment made it difficult, numbing him to violence and death.

Even worse was his sickle cell anemia. For all his life, his illness tortured him with excruciating pain that made him “curse Mother Nature” and question God’s existence.

God and suffering

Prodigy often tried reconciling the idea of a God with a life of pain and suffering.

His verse on the song “Pearly Gates” (2006) mocked God for allowing him to live a “painful” life:

Now homie, if I go to hell and you make it to the pearly gate

Tell the boss man we got beef

And tell his son, I’m gon’ see him when I see him

And when I see him, I’m gon’ beat him like [in] the movie

Prodigy referenced Judeo-Christian imagery in his artistry and took an overt interest in Black American movements influenced by Islamic traditions, but he committed to no religion.

Instead, Prodigy sought the sacred within himself as well as in a perennial force or power that could be used for good or evil purposes.

‘Shadow’ of negativity

In his book, Prodigy recalled how, around 1995, a strange man relayed a message to him saying Prodigy was a powerful man, an angel from the Book of Revelation, and that God placed him on Earth for a reason.

He also recalled seeing a green fiery UFO around 1998 during a positive time in life. This UFO was auspicious because, as Prodigy explained, God’s angels use green fire as opposed to “evil forces” that use red.

Around 2004, however, Prodigy saw another UFO that shined an array of lights into his home. But having relapsed into a negative lifestyle, this UFO made him feel like a “fallen angel.”

Only a few years prior, he saw a “shadow” of his own “negativity” that began consuming his “mind, body and soul.”

Therefore, despite the signs of his angelic nature, he was still torn in a war of spiritual conflict.

‘Positive and negative war’

Prodigy often rapped about a positive and negative war but against real or imagined structures of power.

On the hip hop group Almighty RSO’s “War’s On” (1996), he explicitly said that a “positive and negative war will soon kindle” against white supremacists, secret societies and government authorities:

Now we got illuminati all on our backs

Check and see if we do crimes and pay tax

The war is on, no time to (re)lax

Build an arsenal, got word back from apostle

Unoriginal man got plans colossal

Undelay, n-gg- get your shit straight

Fuck a pearly white gate, all that bullshit is fake

His verse on the 1999 track “Bulworth” relayed a similar point, warning of “foul energies” but also testing our own readiness for an apocalypse ahead:

While you rely on religion

I hold a nine on the mission

To pull fire on your opposition

Revelation was a vision of this

Crack the heavens; it’s time to bring the biz-ness

From 2008 to 2017, Prodigy wrote songs like “Real Power is People,” “Illuminati,” “Black Devil” and “Tyranny” that said positive or negative disposition mattered more than one’s race, religion or class in a war against mass control.

‘Yeah, it’s a spiritual war’

Before his death, however, Prodigy released the album Volume 1, The Book of Revelation, of The Hegelian Dialectic. Prodigy planned this album as part of a three-volume magnum opus.

Volume 2, The Book of Heroine, was posthumously released in 2022 and fans still await Volume 3, The Book of the Dead.

Prodigy framed the project as dealing with the positive and negative stages leading to a “civil war.” But as a work of introspection, The Book of Revelation addressed a war within one’s own “mental, physical and spiritual” self.

Rap History: Prodigy – ‘Hegelian Dialectic (The Book of Revelation)’, released January 20, 2017. pic.twitter.com/4jUSahlxn2

— Grown Up Rap (@GrownUpRap) January 20, 2022

Thus, Prodigy’s most mature project shows that his positive and negative war could be a mythical metaphor for a microcosmic and personal struggle.

“The Good Fight”

Seven years after Prodigy’s passing, a notable song from the Book of Revelation, “The Good Fight,” is suggestive of how this fallen angel aligned himself between conflicting forces.

And I’m fighting the good fight

Rather die swinging, everybody dies

Man life too quick

I need more time to live, because I ain’t done yet

Marcus Evans, PhD. candidate. Department of Religious Studies, McMaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.