More than 200 years after her death, Jane Austen’s views on slavery remain unclear. Jim Dyson/Getty Images

by Devoney Looser, Arizona State University

More than two centuries after Jane Austen died in 1817, many of the English novelist’s fans want to know her takes on her day’s big issues, including race, colonialism and slavery.

Vigorous debates continue about what she may have thought, but her family’s engagement in the movement to abolish slavery is gradually coming to light.

After scouring 19th-century newspapers and archives for new information, I have discovered that three of Austen’s brothers publicly participated in the abolition movement in the years after her death.

The efforts of one of her brothers, which I unearthed from historical records, are described here for the first time and will be included in my forthcoming book, “Wild for Austen,” in 2025.

Race and slavery in Austen’s novels

Many readers suspect Austen was critical of colonial slavery’s violence and harm, but there’s no consensus on this question. Austen, the author of “Pride and Prejudice” and other classic novels, includes the words “slave” and “slavery” in her fiction on nearly a dozen occasions.

Her last unfinished novel, “Sanditon,” features a mixed-race character named Miss Lambe. She is described as a “half mulatto” heiress from the West Indies.

Timid heroine Fanny Price of “Mansfield Park” asks her imperious uncle Sir Thomas Bertram – who is himself an enslaver – a question about the slave trade. Readers aren’t told how he answers, just that she drops the subject when his response meets with “such a dead silence” from her incurious cousins.

In “Emma,” penniless Jane Fairfax controversially compares being hired as a governess with the miseries of the slave trade. She calls both enslaved people and governesses “victims.”

Experts disagree about whether these examples show Austen’s tacit acceptance or implied criticism of slavery.

Great Britain and colonial slavery

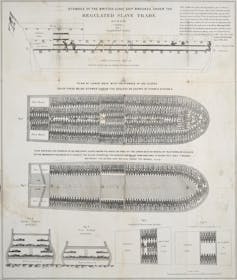

Starting in the 1660s, Great Britain brutally transported about 3.4 million Africans to be enslaved in the Americas – with about half a million dying during the harrowing journey known as the Middle Passage. Many of these enslaved people ended up in Britain’s Caribbean colonies, called the West Indies.

Decades of campaigning by 18th-century abolitionists led to the slave trade’s ban in the British Empire in 1807.

It took more than 20 years of further activism before Parliament abolished slavery in most British colonies in 1833. This was more than three decades before the United States followed suit.

Although Austen died before abolition, the antislavery movement was at full tilt during her lifetime. Her writings offer few clues about her political views, but one surviving letter mentions her love for author and noted abolitionist Thomas Clarkson.

Still, there’s no evidence she openly contributed to the work of his campaigns or other antislavery societies.

Profits from slavery

Some of Austen’s relatives had direct economic ties to slavery.

One was her aunt Jane Leigh Perrot, born into an affluent family of enslavers in Barbados. That aunt had married the wealthy brother of Jane Austen’s mother. The Leigh Perrots stood to inherit a share of her late father’s plantation. Their combined fortune was eventually bequeathed to descendants of James Austen-Leigh, Jane’s eldest brother, who added the surname Leigh in 1837.

There were other Austen family connections to enslavers.

Until 2021, many scholars believed Rev. George Austen, Jane Austen’s father, stood to benefit financially from the Antigua plantation of his former Oxford student, James Langford Nibbs. Rev. Austen was said to have been that plantation’s trustee, but there were significant misunderstandings about his purported role.

Rev. Austen was actually a co-trustee to Nibbs’ 1760 marriage settlement, having just served as the clergyman who married Nibbs and his wife, as I discovered. Rev. Austen’s uncompensated co-trusteeship “would never have involved him in any duties connected with running a plantation,” as legal scholar John Avery Jones has argued.

Research on connections between the Austen family and slavery proceeds.

3 abolitionist brothers

What’s come to light, through my ongoing research, is that three of Jane’s six brothers later became publicly involved in the abolition movement.

One of them was Capt. Charles John Austen. He policed the illegal slave trade in the West Indies in the Royal Navy. He wrote a letter to an English newspaper about his August 1826 capture of a slave ship and shared his observations about the horrific conditions endured by enslaved people on board. His actions, however, allowed the slaver to escape, as I found by examining long overlooked government documents.

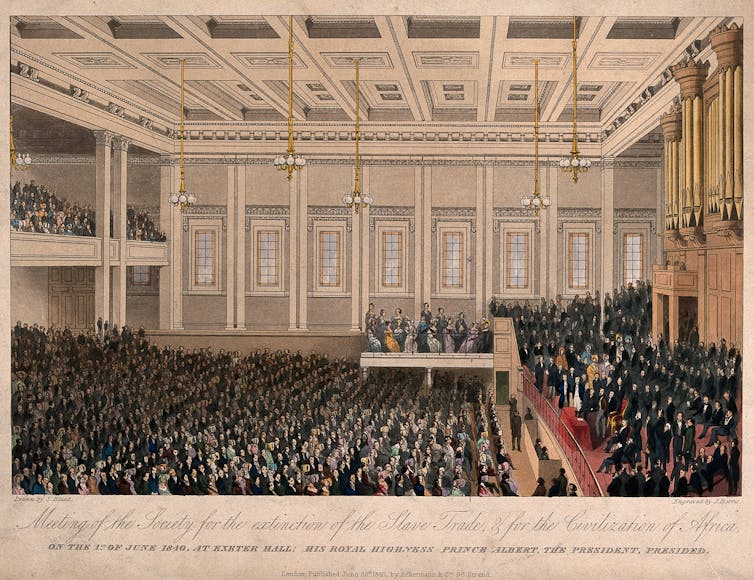

More prominent was the abolitionist work of Jane’s brother Henry Thomas Austen, a failed banker turned clergyman. He served as a delegate to the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London in 1840, as I first reported in 2021. This fact hadn’t been noticed before, apparently because Henry was then using the name Rev. H. T. Austen. Previous scholars hadn’t realized he was Jane’s brother.

To this expanding Austen family abolitionist history we may now add a third Austen brother, Francis “Frank” William Austen.

It has long been known that Frank, a naval officer, privately expressed abolitionist views. What my new research has uncovered is that he worked openly as a local antislavery activist after Jane’s 1817 death but before the British government passed the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act.

That makes Frank the earliest known antislavery activist in Jane Austen’s immediate family.

A motion to end slavery

A short announcement in the Hampshire Chronicle on Feb. 6, 1826, relays: “The Magistrates at Gosport, in compliance with the requisition of many inhabitants, have appointed a meeting for Friday next, to consider the propriety of petitioning Parliament for the Abolition of Slavery in the West India Colonies.”

Frank Austen took a leadership role there, a previously unnoticed fact. At that meeting, “a petition to the House of Commons, praying the abolition of slavery in the West India Colonies, was agreed to.” Capt. Austen of the Royal Navy – Frank Austen – made the motion for the petition’s approval, which then passed.

The abolitionist work in the coastal town of Gosport was part of a national movement. Many cities submitted petitions to an inattentive Parliament. In nearby Portsmouth, a 66-foot-long petition signed by 3,187 people had been sent, “praying for the abolition of negro slavery in the West Indies,” according to another dispatch in the Hampshire Chronicle.

“Praying” here means “requesting,” although there was a spiritual element involved. Prominent members of the British clergy in Bath took a leading role in preparing the petition there. In Gosport, however, the antislavery action came from Frank Austen, along with a solicitor, a surgeon, a grocer and a baker.

The resolution Frank Austen moved to accept called slavery “repugnant.” It demanded “measures … most conducive to the immediate Amelioration of the condition of the Slave population, as well as the gradual but total extinction of Slavery,” according to a report in the Hampshire Telegraph on Feb. 13, 1826.

More to learn

The Jane Austen House Museum in Chawton, England, recently ran an exhibit about Frank Austen, who was born 250 years ago, in 1774. There’s more to learn not only about Jane Austen’s own views of slavery but about Frank Austen himself.

That museum also announced its acquisition of Frank’s unpublished memoir and sketchbook, for which it sought crowd-sourced transcription. Once it’s publicly shared, the memoir could cast further light on his beliefs.

In the meantime, scholars continue to seek new facts, to speculate about what Jane Austen’s fiction says between the lines and to investigate what she may have believed about slavery and abolition. This is happening ahead of the 250th anniversary of her birth on Dec. 16, 2025.

Taken together, these discoveries about the abolitionist activism of three of Jane Austen’s six brothers add weight to the theory that by the end of her life, cut short by illness at age 41, the novelist may herself have been on the road to becoming a passionate, active and public supporter of abolition.

Devoney Looser, Regents Professor of English, Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.