Cuban leader Fidel Castro checks out former U.S. President Jimmy Carter’s pitching form prior to a baseball game in Havana in 2002. Sven Creutzmann/Mambo Photography via Getty Images

by Howard Manly, The Conversation

In Mark 8:34-38, a question is asked: “For what shall it profit a man, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?”

As Jimmy Carter celebrates his 100th birthday, it’s hard to question whether the former U.S. president ever lost his soul.

A person who served others, Carter did more to champion the cause of human rights than any U.S. president in American history. That tireless commitment “to advance democracy and human rights” was noted by the Nobel committee when it honored Carter with its peace prize in 2002.

From establishing the nonprofit Carter Center to working for Habitat for Humanity, Carter never abandoned his moral compass in his public policies or personal contributions to society.

Over the years, The Conversation U.S. has published numerous articles exploring the legacy of the nation’s 39th president – and his exemplary life after leaving the world of American politics. Here are selections from those articles.

1. A preacher at heart

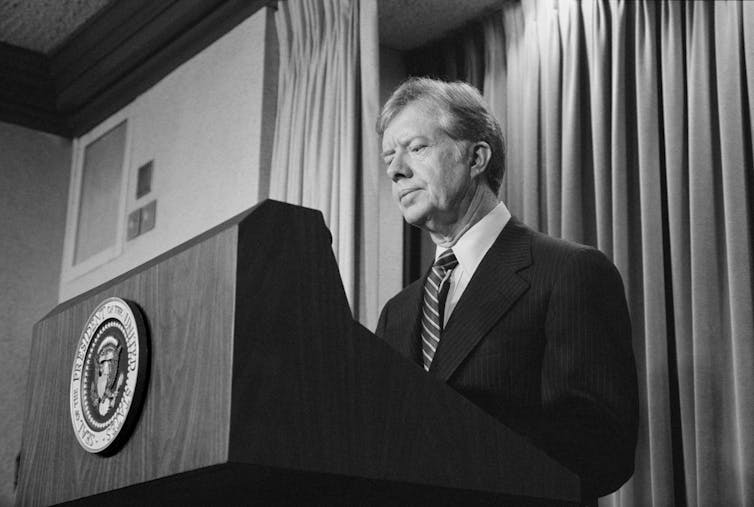

As a scholar of American religious history, Asbury University Professor David Swartz believes that a speech Carter gave on July 15, 1979, was the most theologically profound speech by an American president since Lincoln’s second inaugural address, on March 4, 1865.

Carter’s nationally televised sermon was watched by 65 million Americans as he “intoned an evangelical-sounding lament about a crisis of the American spirit,” Swartz wrote.

“All the legislation in the world,” Carter proclaimed during the speech, “can’t fix what’s wrong with America.”

What was wrong, Carter believed, was self-indulgence and consumption.

“Human identity is no longer defined by what one does but by what one owns,” Carter preached. But “owning things and consuming things does not satisfy our longing for meaning.”

2. Tough-minded policies on human rights

After Iranian religious militants seized the U.S. Embassy in Tehran in 1979, Carter was considered a weak leader. But his overseas policies were far more effective than critics have claimed, wrote Gonzaga University historian Robert C. Donnelly – especially when it came to the former Soviet Union.

Shortly after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, for instance, Carter imposed an embargo on U.S. grain sales that targeted the Soviet Union’s dependence on imported wheat and corn to feed its population.

To further punish the Soviets, Carter persuaded the U.S. Olympic Committee to refrain from competing in the upcoming Moscow Olympics while the Soviets repressed their own people and occupied Afghanistan.

Among Carter’s critics, none was harsher than Ronald Reagan. But in 1986, after beating Carter for the White House, even he had to acknowledge Carter’s foresight in modernizing the nation’s military forces. Those efforts by Carter further increased economic and diplomatic pressure on the Soviets.

“Reagan admitted that he felt very bad for misstating Carter’s policies and record on defense,” Donnelly wrote.

3. Carter’s unexpected liberal foe

Reagan’s win over Carter in the 1980 U.S. presidential race was due in part to Carter’s bitter race during the Democratic primary against an heir to one of America’s great political families – Ted Kennedy.

Kennedy’s decision to run against Carter was “something of a shock to Carter,” wrote Thomas J. Whalen, a Boston University associate professor of social science.

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

In 1979, Kennedy had pledged to support Carter’s reelection bid but later succumbed to pressure in liberal Democratic circles to launch his own presidential bid and fulfill his family’s destiny.

In addition, Whalen wrote, Kennedy “harbored deep reservations about Carter’s leadership, especially in the wake of a faltering domestic economy, high inflation and the seizure of the American Embassy in Iran by radical Muslim students.”

In response, Carter vowed to “whip (Kennedy’s) ass.”

And he did.

But that win over Kennedy came at a high cost.

“Having expended so much political and financial capital fending off Kennedy’s challenge,” Whalen wrote, “he was easy pickings for Reagan in that fall’s general election.

4. A quiet fight against a deadly disease

Guinea worm is a painful parasitic disease that is contracted when people consume water from stagnant sources contaminated with the worm’s larvae.

Clemson University Professor Kimberly Paul has worked as a parasitologist for over two decades.

“I know the suffering that parasitic diseases like Guinea worm infections inflict on humanity, especially on the world’s most vulnerable and poor communities,” she wrote.

In 1986, it infected an estimated 3.5 million people per year in 21 countries in Africa and Asia.

Since then, that number has been reduced by more than 99.99% to 13 provisional cases in 2022, in large part because of Carter and his efforts to eradicate the disease. Those efforts included teaching people to filter all drinking water.

Over time, Carter’s efforts proved tremendously successful. On Jan. 24, 2023, the Carter Center announced that “Guinea worm is poised to become the second human disease in history to be eradicated.”

The first was smallpox.

5. Carter’s brave step in Cuba

In 2002, long after his departure from the White House in 1981, Carter became the first U.S. president to visit Cuba since the 1959 Cuban revolution. Carter had accepted the invitation of then-President Fidel Castro.

Jennifer Lynn McCoy, now at Georgia State University, was director of the Carter Center’s Americas Program at the time. She accompanied Carter on that trip in which he gave a speech in Spanish that called on Castro to lift restrictions on free speech and assembly, among other constitutional reforms.

Castro was unmoved by the speech but instead invited Carter to watch a Cuban all-star baseball game.

At the game, McCoy wrote, “Castro asked Carter for a favor” – to walk to the pitcher’s mound without his security detail to show how much confidence he had in the Cuban people.

Over the objections of his Secret Service agents, Carter obliged and walked to the mound with Castro and threw out the first pitch.

Carter’s move was a symbol of what normal relations could look like between the two nations – and of Carter’s unwavering faith.

This story is a roundup of articles from The Conversation’s archives.

Howard Manly, Race + Equity Editor, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.