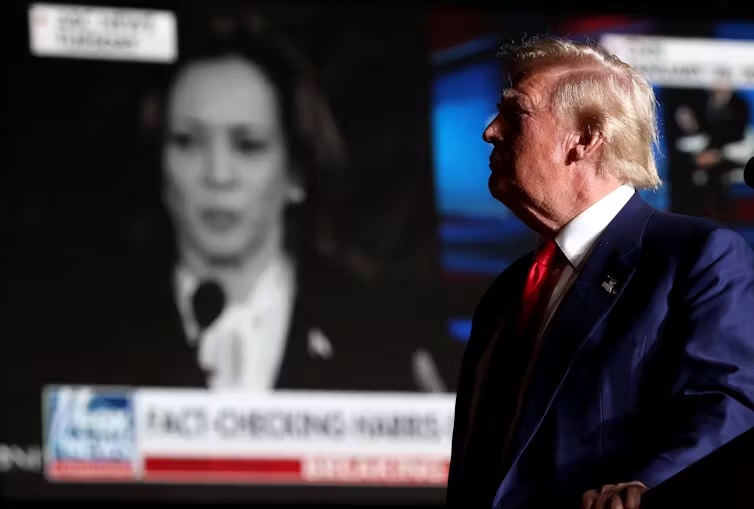

Who will represent the U.S. better on the global stage? Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

by Garret Martin, American University School of International Service

According to conventional wisdom, U.S. voters are largely motivated by domestic concerns and especially the economy.

But the upcoming presidential election may be somewhat of an outlier. In a September 2024 poll, foreign policy actually ranks quite high in voters’ concerns – with more Democrats and Republicans combined saying it was “very important” to their vote than, say, immigration and abortion.

As such, understanding where Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump and Democratic rival Kamala Harris stand on the significant international issues of the day is important. And we can do so by looking at the records of their respective administrations in the three regions they prioritized: the Indo-Pacific, Europe and the Middle East.

Donald Trump: Disrupter-in-chief

In his 2017 inaugural address, Trump painted a dark picture of the U.S. In his telling, his country was being taken advantage of by other nations, especially in trade and security, while neglecting domestic challenges.

To disrupt this, Trump promised an “America First” approach to guide his administration.

And in practice, his foreign policy certainly proved disruptive. He showed a clear willingness to buck traditions and undid some of former President Barack Obama’s signature policies, such as the Iran nuclear deal, which exchanged sanctions relief for restrictions on Tehran’s domestic nuclear program, and the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement.

In so doing, he ruffled the feathers of allies and foes alike.

Trans-Atlantic relations were tense under Trump, especially because of his hostility toward NATO. After deriding the Atlantic alliance on the campaign trail, Trump stuck to the same tune while in office. He routinely insulted allies at high-level summits and allegedly came close to withdrawing from the alliance altogether in 2018.

Donald Trump meets Russian President Vladimir Putin in June 2019. Kremlin Press Office/Handout/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

While NATO did make inroads in bolstering its Eastern flank in that period, the alliance was primarily defined by internal turmoil and limited cohesion during Trump’s time in office. U.S. relations with the European Union hardly fared better. In 2018, the U.S. imposed steel and aluminum tariffs on the European Union, citing national security concerns.

Trump also broke with previous U.S. presidents in his administration’s Asia policy. One of his first moves in 2017 was to abandon the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a trade deal negotiated by Obama. Trump’s late 2017 national security strategy also announced a major shift toward China, labeling it as a “strategic competitor” – implying a greater emphasis on containing China as opposed to cooperating with it.

This hawkish turn played out especially in the field of trade. Trump’s administration imposed four rounds of tariffs in 2018-19, affecting US$360 billion of Chinese goods. Beijing, of course, responded with tariffs of its own. The two countries did sign a so-called phase-one deal in January 2020 that sought to lower the stakes of this trade war. But the COVID-19 pandemic nullified any chance of success, and relations soured further with each Trump utterance of the pandemic being a “Chinese virus.”

Trump showcased somewhat contradictory impulses toward the Middle East and other issues. He pushed for disengagement and to undo Obama’s major policies. Besides withdrawing from the Paris climate accords in 2017, Trump abandoned the Iran nuclear deal in 2018. His administration also signed a deal to end the U.S. presence in Afghanistan, and it withdrew forces from northern Syria.

But at the same time, Trump continued the bombing campaign against the Islamic State group in Syria and Iraq and authorized the killing of Iranian Gen. Qasem Soleimani in 2020. The latter was consistent with a policy that aimed to pressure and isolate Iran economically and diplomatically. The key example of the diplomatic pressure came through especially via the Abraham Accords through which Trump helped facilitate the establishment of normal diplomatic ties between Israel and the UAE, Bahrain and Morocco.

Kamala Harris: Alliance and engagement

Although not taking a driving role in foreign policy, Harris has been part of an administration that has committed the U.S. to repairing alliances and engaging with the world.

This came across by undoing some major actions from the Trump administration. For example, the U.S. quickly rejoined the Paris climate accords and overturned a decision to leave the World Health Organization.

But in other areas, the Biden administration has shown more continuity with Trump than many expected.

For instance, the U.S. under Biden has not fundamentally deviated from strategic competition with China, even though the tactics have differed a little. The administration maintained Trump’s tariff approach, even adding its own targeted rounds against Beijing on electric vehicles.

Moreover, it cultivated different diplomatic platforms in the Indo-Pacific to act as a counterweight to China. This included the cultivation of the Quad dialogue with Australia, India and Japan, and the AUKUS deal with Australia and the U.K., both of which attempted to further the Biden administration’s strategy of containing China’s influence by enlisting regional allies. Finally, the Biden administration did maintain some channels of communication with China at the highest level as well, with Biden meeting Xi Jinping twice during his presidency.

The Biden administration’s Middle Eastern policy displayed significant continuity with Trump’s approach – at first. While it turned out to be chaotic, the U.S. completed the withdrawal of its troops from Afghanistan in summer 2021, as had been agreed under Trump. The Biden administration also embraced the format and goals of the Abraham Accords. It even tried to build on them, with the goal of fostering Israeli-Saudi diplomatic ties.

Of course, the attacks of Oct. 7, 2023, in Israel completely changed the equation in the Middle East. Preventing the spiral of violence in the region has become an all-consuming task. Since then, Biden and Harris have tried, largely unsuccessfully, to balance support for Israel with mediation efforts to liberate the hostages and to ensure a cease-fire.

Trans-Atlantic relations, however, are an area where there were marked differences in the past four years. The tone of the Biden-Harris administration has been in sharp contrast with that of Trump, reaffirming frequently its clear commitment to NATO. And once Russia launched its illegal invasion in February 2022, the U.S. placed itself at the forefront of supporting Ukraine.

Harris has suggested that she would continue Biden’s policy of providing Kyiv with extensive and continuous military support. In conjunction with allies, the White House of Biden and Harris also implemented a broad range of sanctions against Russia. But the U.S. under Biden has not yet been willing to support Ukraine’s immediate entry into NATO.

What next?

Based on their records, what could we expect of a Trump or Harris presidency?

It’s unlikely either candidate will abandon strategic competition with China. But Trump is more likely to seriously escalate the trade war, promising extensive tariffs against Beijing. Trump’s commitment to defending Taiwan is also more ambiguous in comparison with Harris’ pledges.

U.S. policy toward Europe will largely depend on the results of the election. Harris has frequently underlined her steadfast support for NATO, as well as for Ukraine. Trump, on the other hand, is showing signs that he is unwilling to further aid the regime in Kyiv.

And for the Middle East, it remains to be seen whether either Trump or Harris would be able to better shape events in the region.

Garret Martin, Senior Professorial Lecturer, Co-Director Transatlantic Policy Center, American University School of International Service

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.