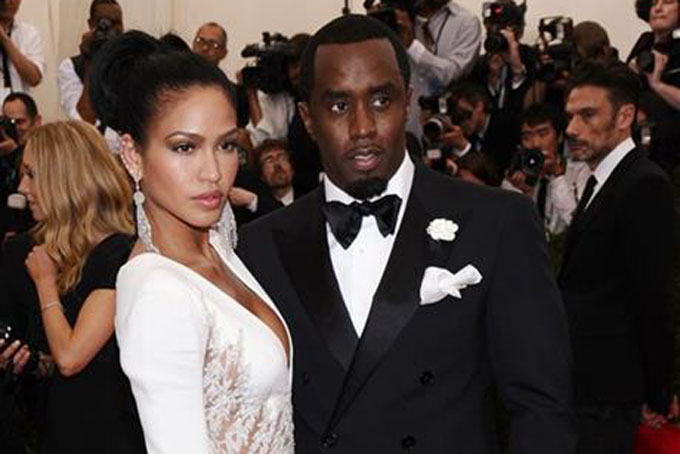

In this May 4, 2015 file photo, Cassie, left, and Sean “Diddy” Combs arrive at The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute benefit gala celebrating “China: Through the Looking Glass” in New York. (Photo by Charles Sykes/Invision/AP, FIle)

The recent arrest of Sean “Diddy” Combs brings up issues of misogyny and violence toward Black women. This issue extends beyond Hip-Hop, spreading into Black liberation spaces and our communities. In Hip-Hop, it manifests in various ways, such as the portrayal of Black women in the music as well as the over-sexualization and policing of our bodies.

Some suggest this began in the 1980s with gangster rap, but as someone born in 1980, I remember witnessing the effects of misogyny and exploitation much earlier. For example, the UTFO song “Roxanne, Roxanne,” where the group describes catcalling, reminds me of my experiences of being catcalled at the age of ten. I have always been thick, and this began when I was in middle school. At times, this made it hard to walk home from school, with older men, young men, and even older women pointing out my hips and thighs—something that still happens today. Let me add that as a thick Black girl, we don’t need reminders that we are thick. The song made me uncomfortable and helped to normalize misogyny. When Roxanne Shante responded, it was my first memory of Black feminism. It may sound surprising, but for a Black woman to speak truth to power at that time was incredibly powerful.

This trend of misogyny and Black women in Hip-Hop fighting back continued. Despite Black women like Salt-N-Pepa and Lil’ Kim reclaiming their power through their music, misogyny has worsened, with lyrics that demean Black women and perpetuate sexual violence. Examples include older artists being in relationships with younger Black girls, songs that depict gender violence, as well as the silence surrounding the women who did speak out against some of your “faves.” The acceptance and normalization of this are connected to how it manifests in our communities and Black liberation spaces.

Specifically, in the hood with older men parking across the street after school and making comments to young Black girls. This includes whistling, courting (buying gifts/giving them money), and openly discussing waiting until the girls turn 18. It’s important to acknowledge that this behavior also affects young Black boys, with older Black women often putting them in similar situations, etc.

This toxicity also appears in the movement for Black liberation, where Black women are sometimes separated from the cause due to misogyny. I, too, have experienced being overlooked, ignored, or erased because I am deemed too strong, or not submissive enough. This was discussed by the Combahee River Collective. A Black feminist lesbian organization released a statement calling this behavior out in 1977. To this day it remains a crucial text in Black feminism. The authors boldly called out this behavior, stating, “We struggle together with Black men against racism, while we also struggle with Black men about sexism.”

To address this issue, we must be willing to engage in courageous conversations about Black misogyny and how it manifests. Additionally, create safe spaces where Black women can speak up and be believed. And yes, this means going beyond podcasts! Don’t get me wrong, I enjoy a good podcast. However, the overwhelming amount of advice directed at Black women and the policing of our experiences is not helpful. The silence has gone on for far too long, which is why there are so many Cassies in our communities. We must support and protect Black women in REAL LIFE!