U.S. Steel’s Edgar Thomson Works photographed in February 2023. (Photo by Quinn Glabicki/PublicSource)

Their towns have hosted U.S. Steel plants for generations. They see foreign investment as their best path forward.

“PublicSource is an independent nonprofit newsroom serving the Pittsburgh region. Sign up for our free newsletters.”

“If these guys are our allies, why are we making them our enemy?” said Cletus Lee, the mayor of North Braddock, referring to Japan’s nearly 80 years of friendship with the U.S. “We have diversity coming into America. Why don’t we implement that we are the land of the free, as opposed to saying that we have exceptions to what is going on on our American soil?”

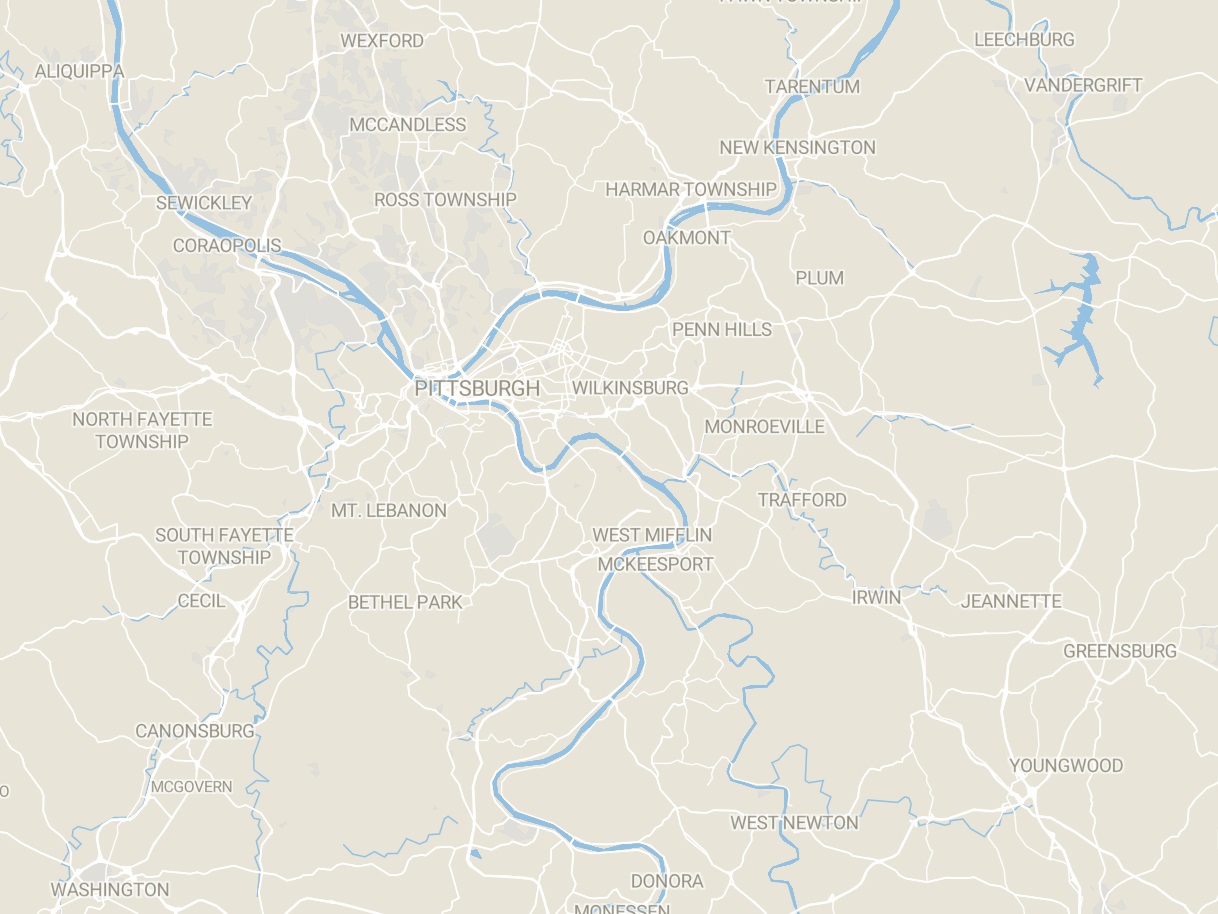

Nippon Steel Corp.’s attempt to take over the historic Pittsburgh company is approaching a resolution as federal regulators near a late December deadline to decide whether to recommend blocking it. Whether they do so could have major consequences for places including Braddock, Clairton and West Mifflin, towns that have faced population decline and economic woes for years but have been buoyed by continued steelmaking operations while most other plants in the region closed.

The mayors have no formal power over the decision. That power belongs to the White House. The mayors are emerging, though, as a counterpoint to the United Steelworkers of America [USW] union, which has been a persistent voice in opposition.

Echoes of 1980s shutdowns

Rich Lattanzi was apprehensive when U.S. Steel announced in December that the historic Pittsburgh company had struck a deal to be taken over by Japanese-owned Nippon Steel, for $55 a share, or roughly $14 billion.

“I’m thinking, a foreign company, oh my God, here we go,” said Lattanzi, the mayor of Clairton. “Maybe the Clairton mill might get shut down and sold off.”

U.S. Steel’s Mon Valley Works

Created with Datawrapper

Home to the Clairton Coke Works, the Mon Valley city takes in more than a quarter of its property tax revenue from U.S. Steel. According to Lattanzi, U.S. Steel pays upwards of $300,000 in property taxes to the city each year, and the city’s 2024 budget projects about $1.2 million in total property tax revenue. The plant’s closure would be devastating, Lattanzi said.

Lattanzi joins other Mon Valley mayors — who like him, oversee towns that have endured decades of population decline and run on tenuous budgets — who have come around on the Nippon purchase of Pittsburgh’s iconic steelmaker.

Their changes of heart were driven by two factors: The prospect of losing the Mon Valley plants altogether if the sale is blocked, and Nippon’s pledge to not only keep the plants open, but to modernize them.

U.S. Steel CEO David Burritt said in September that if the sale is blocked, the company could be forced to close its Mon Valley Works, which consists of the Irvin Works in West Mifflin, the Edgar Thomson Works in Braddock and the Clairton Coke Works.

By contrast, Nippon leader Takahiro Mori said in August that his firm would invest more than $1.3 billion in updating the plants if they acquire them.

Chris Kelly, the mayor of West Mifflin, said he was born in Homestead and saw firsthand the mid-1980s closure of a major steel plant there, on the site of the present day Waterfront shopping complex.

“I saw what happened when they didn’t modernize,” Kelly said. “The closing of the plant ruined the community. It took several decades to start to recoup.”

The deal is still in limbo because the federal government is determining whether foreign ownership would constitute a national security risk. The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States [CFIUS] is expected to make a recommendation to President Joe Biden by the end of the year on whether to block the sale. Biden could act on the recommendation quickly, or it could sit until the inauguration of President-Elect Donald Trump on Jan. 20.

Both Biden and Trump opposed the sale ahead of the November presidential election, though neither has commented on it since.

U.S. Steel’s Edgar Thomson Works photographed in February 2023. (Photo by Quinn Glabicki/PublicSource)

‘Honorable,’ not a threat

Mori and other Nippon executives traveled to Pittsburgh and Washington, D.C. last week to push the deal, including meetings with Mon Valley mayors who have no say over its approval but will have to live with the consequences.

“I think they’re honorable people,” Lattanzi said of the Nippon representatives. “They looked me right in the face, eye contact. It all sounded pretty real to me.”

Mori paid a visit to Kelly last Tuesday in the garage that he converted into a mayoral office.

“The more I meet them the more I’m taken aback by their soft-spoken, polite business savvy,” Kelly said. “You learn a lot about somebody in two hours sitting at a table like we were. You learn about their families and their commitments.”

CFIUS’ concern, centered on whether Japanese ownership of American steel production constitutes a national security threat, did not resonate with Mon Valley leaders.

“The Japanese people, they are our allies already,” said Delia Lennon-Winstead, the mayor of Braddock. “They’re here to help and they’re already established in the U.S.”

Kelly said the Irvin works primarily makes sheet metal for washers, dryers and microwaves.

“Are we going to drop fucking microwaves on top of Alabama?” Kelly said. “It’s not a national security threat.

“People won’t forget Pearl Harbor. My response to them is: Let’s go to war with Germany. Vietnam. Hell, let’s go all the way back to the king of England. [Japan] is our strongest ally now. The 7th Fleet is stationed there. That’s 20,000 sailors.”

West Mifflin Mayor Chris Kelly carries out his municipal duties from his garage office in November 2024. (Photos by Charlie Wolfson/PublicSource)

Union vs. mayors

The USW union has opposed the sale to Nippon since it was announced, and stated a preference for an offer from Cleveland Cliffs to take over U.S. Steel for the equivalent of $35 per share — considerably less money than Nippon offered.

“Since the deal was announced, neither company has meaningfully addressed the long-term implications of the sale for USW jobs or the communities that depend on them,” said USW President David McCall in a written statement responding to PublicSource questions. He accused Nippon of unfair trade practices and of trying to “injure our workers” and “subvert our domestic industry from within.”

“The best way to protect jobs … is for this deal to be rejected.”

USW spokesperson Jess Kamm added that the local mayors have not made any direct outreach to USW leadership.

“We would expect community leaders to be concerned, as we are, about the long-term future of steelmaking in the Mon Valley rather than listening to the threats of a bully.”

U.S. Steel and Nippon Steel did not respond to requests for comment.

Lattanzi said he sympathizes with the union leadership, who he thinks are trying to “save face” in opposing the deal. “But me being the mayor of the City of Clairton, being a poor town, I’m just trying to make ends meet.”

Kelly criticized the USW for its opposition, accusing McCall of failing to visit and engage with the plants where jobs are at stake.

“How do you represent somebody that may be losing their job and you don’t even come and talk to them?” Kelly said. “What kind of brotherhood is that?”

Kamm refuted that claim, saying McCall has in fact visited the Edgar Thomson, Irvin and Clairton plants in the past, though she did not specify whether it happened since the Nippon deal came under scrutiny and did not answer a follow-up question on the timing of the visit.

While union leadership is staunchly opposed, it’s unclear where the rank and file membership stands. A handful of steelworkers appeared in a TV ad promoting the deal, along with a handful of Mon Valley mayors. Kelly and Lattanzi said the majority of steelworkers they talk to want the deal to be approved.

Some cited a Nippon-sponsored trip to the Japanese firm’s plant in Follansbee, West Virginia, where they said union workers reported satisfaction with Nippon’s management.

The stakes

“If we were to lose the mill, it would be devastating for the City of Clairton,” Lattanzi said.

He said the city lives “paycheck to paycheck” and the end of U.S. Steel in the region would cost the city between $300,000 and $500,000 annually, leading to layoffs.

“The city would regress,” Lattanzi said. “Probably more crime, and you wouldn’t want to live here because there would be no jobs and nothing happening.”

North Braddock’s Lee said the deal’s failure could cost the region over 4,000 jobs and displace many more.

“Strength is in numbers,” Lee said. “We have to do things now, not on a selfish end but on an end to help our communities be vital. I think a non-merger would kill that. It would destroy not just our communities but surrounding communities.”

“It will help our community and maybe make it vital again,” Lee said while handing out turkeys at the Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank in Duquesne a week before Thanksgiving. “We have a lot of situations with blight. We have a lot of situations with why we’re here right now, food insecurity.

“We can’t think singular anymore. We have to think plural.”

Charlie Wolfson is PublicSource’s local government reporter. He can be reached at charlie@publicsource.org.

This story was fact-checked by Rich Lord.

This article first appeared on PublicSource and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.