Duquesne University students spent a semester with incarcerated individuals using Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” as a means to discuss justice and “squash the beef.”

“PublicSource is an independent nonprofit newsroom serving the Pittsburgh region. Sign up for our free newsletters.”

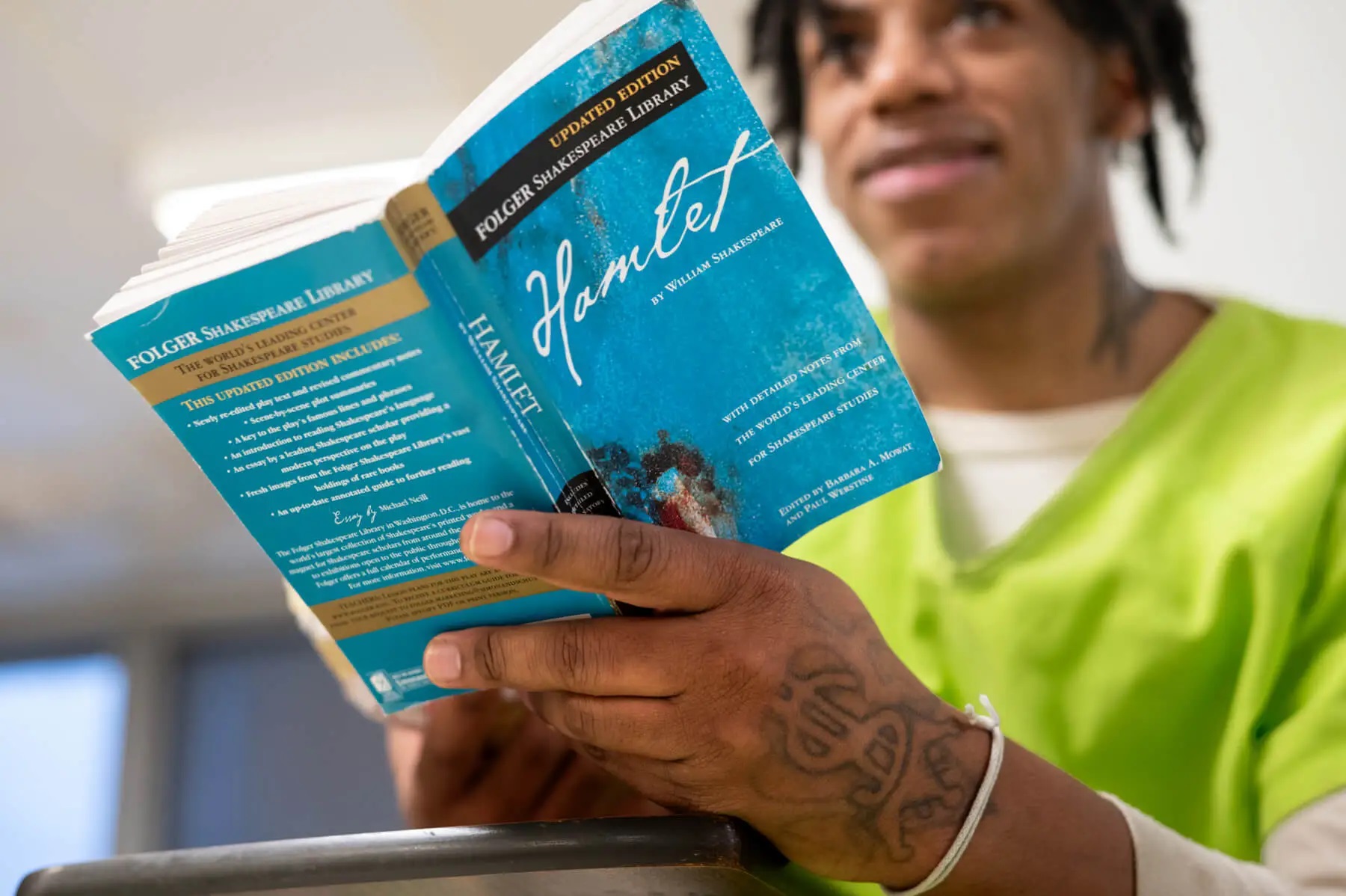

Shawn Daniels lifts himself out of a rigid chair, walks to the middle of the room and launches into a soliloquy. He’s reciting lines from the titular character in the Shakespeare play, “Hamlet,” to a group of around 20 students at the Allegheny County Jail.

It’s just after 9 a.m., but no one seems tired — especially Daniels.

He moves around the drab room that stands in for a Danish castle, catching eyes with everyone seated and inflecting his voice.

“Am I a coward?” he softly asks. “Who calls me villain?”

Shawn Daniels performs as Hamlet during a class of people incarcerated at Allegheny County Jail and Duquesne University students, on Nov. 14, at the jail in Uptown. Daniels’ emotional performance was met with eager applause from his classmates. (Video by Stephanie Strasburg/PublicSource)

The scene ends and the floor opens for feedback. Susan Stein, one of the teachers in the room — and the only one with a theater background — asks the class, “What did you get from that?”

“He’s ashamed,” someone answers. Stein agrees and coaxes two more performances out of Daniels: first with the anger ratcheted up, then faster. “Don’t think, just go,” she says.

By the third run-through, Daniels is stamping his feet against the floor and cradling his face in his hands.

This is what happens when you meet Shakespeare halfway, Stein said. And this fall, it’s what two Duquesne University courses, attended by both first-year students and incarcerated individuals, have encouraged.

Students took two courses in tandem, titled “Introduction to Criminal Justice” and “Democracy and Justice.” They spent their mornings together twice a week, studying “Hamlet” through three disciplines: sociology, philosophy and theater. These are not acting classes — the closest thing to a prop in the room is a makeshift skull constructed from wads of paper and masking tape. Rather, the courses involve the kind of intimate character study that requires performance.

Instead of curtain call, the courses culminate in a restorative justice exercise, a practice that encourages open dialogue to address harms inflicted on someone. Before the play’s fifth act, when (spoiler alert!) most of the prominent characters die, an alternate ending is explored in which the characters — played by students from both groups — try to work out their conflicts in a peacemaking circle.

Borrowing the Bard

“What if we ruined Hamlet?”

That question, Duquesne sociology professor Norman Conti joked, is the concept behind the in-jail courses. Conti’s work teaching in prisons and jails spans more than a decade and has formed the basis for the university’s Elsinore-Bennu Think Tank for Restorative Justice, which he founded in 2013 with six incarcerated individuals he taught. (Elsinore refers to the castle Hamlet stays in.)

Conti’s courses often employ the “inside-out” approach of having on-campus or “outside” and incarcerated or “inside” students in one class. Learning the approach, established at Temple University in 1997, changed Conti’s professional life. It led him to formerly incarcerated people and restorative justice advocates who’ve become frequent collaborators and friends, some of whom are also involved in the think tank.

At the core of it all is a belief in the effectiveness of restorative justice, which Conti said aligns with Duquesne’s commitment to community engagement and allows him to thread the concept into his courses. The exercise at the jail though, due to limited time, isn’t enough to fully illustrate its power. It would take many roundtables to get somewhere, he explained.

Both “Introduction to Criminal Justice” and “Democracy and Justice” are connected under Duquesne’s Justitia learning community in which first-years delve into human rights studies. Conti heads the former class, while philosophy faculty member Jeff McCurry and teaching artist Stein tackle the latter.

Many of the first-year students chose the Justitia learning community because of their desire to be involved in the legal field in the future.

“You want judges and lawyers and whatever else who have been through these kinds of programs,” Conti said. And it’s easier to instill the values garnered from the courses when students are at the beginning of the career pipeline, he explained, rather than after they’re established.

In other semesters Conti has similarly used Hamlet as a framework, but he said none have been as good as this one. Adding Stein to the fold has brought a certain kinetic energy to the courses.

Stein is slight and nimble and tries to get even the shiest of students to tap into their less-expressed emotions. It works, sometimes.

There is method in it

Back in room 1198 at the jail, it seems that incarcerated student Daniels’ performance has set the tone for the others. Duquesne student Evelyn Sorg, playing the ghost of Hamlet’s father, yells in the face of another Duquesne student acting as Hamlet. Then, three Duquesne students playing Ophelia deliver a line reading that makes inside student Davion Morgan say, “I almost fell out of my chair.”

The inside and outside students play off each other in a way that’s reminiscent of a tight-knit high school class. They sit interspersed — an instruction from Conti — joke around and hype each other up during turns.

And they’re not afraid to give their opinions on the source material, or otherwise.

Weeks before the planned restorative justice roundtable exercise, McCurry prompts the class to discuss absolute and relative morality, asking the class which they believe in. Only inside students weigh in, with Daniels leaning toward absolutes, while another incarcerated student said it’s all relative.

It took time to get to that point. The Duquesne students recalled being nervous and coming in with stereotypes, while the incarcerated students initially kept more to themselves, perhaps out of fear of being judged.

The Duquesne students get college credits. For the incarcerated students, participation carries a different weight. While both groups are there by choice, those in jail are in the re-entry program and come to class knowing there’s a high chance they’ll be released in the next year and participation in programs can look good on their record.

Vonzdell Fullum is preparing for release in a few months. Before this fall, he had never studied Shakespeare. One of the most engaged students in the courses, he’d come to class equipped with jokes and insights into characters’ motivations. He said he’s completing the course with a desire to better himself and a new outlook on the criminal justice system.

Vonzdell Fullum performs Shakespeare’s famed “Alas poor Yurick” scene from “Hamlet” during a class of people incarcerated at Allegheny County Jail and Duquesne University students, on Nov. 14, at the jail in Uptown. Fullum speaks to a makeshift “skull” made by Prof. Norman Conti from paper and tape with a face drawn on with marker. (Photos by Stephanie Strasburg/PublicSource)

“It changed my outlook on everything,” said Gerald Miller, another incarcerated student who took the courses.

“Now I can understand why a trial … could take years or months and why people would come back with more questions. Because every question leads to another question.”

Some inside students even got out during the courses, much to the Duquesne students’ delight. Daniels was unexpectedly released a few weeks before the courses ended, having barely served his minimum sentence. Conti wrote a character letter on his behalf, something he’s not done for any other incarcerated student he’s taught at the jail, praising the vigor he brought to the classes.

The first-years have also gleaned a lot from the courses, an opportunity Sorg termed “once-in-a-lifetime.” McCurry said he hopes the benefits have been felt by everyone equally. As someone leading the course from a philosophical lens, he explained that the pursuit of truth is better done collectively than it would be operating in silos.

What dreams may come

The day of the roundtable, the circle is led by Dawn Lehman, a local restorative justice and conflict resolution expert. Lehman has never read Hamlet but is soft-spoken and gently probes the students portraying their characters with questions designed to understand what’s needed for healing.

Accountability is central to restorative justice, but the process can be messy, Lehman says. To her, the world would be a better place if we responded to “violations” with thoughtful questions like, “What would it look like to handle this in a dialogue? What would be the benefits of direct conversation, whether it’s separate from the courts or in conjunction with the courts?”

Nearly all the key players in the roundtable are Duquesne students, except an incarcerated student who portrays Laertes, a character whose father is killed by Hamlet and whose sister, Ophelia, drowns.

First, Lehman asks what brings everyone to the table.

Laertes wants to “get to the bottom” of his father and sister’s deaths. Hamlet’s mother, Gertrude, doesn’t know how she’s feeling and wonders, “Is anybody truly evil?” Claudius, Hamlet’s uncle and stepfather, has come to “squash the beef” with his nephew and rival, the king of Norway.

Everyone wants different things. Lehman has a difficult job.

“Right now, I just need to hear you say you killed my father,” said the student playing Hamlet to that day’s Claudius.

This never happens. Instead, Hamlet and Claudius confer and agree to put on a united front for Denmark’s citizens in return for Claudius’ private confession to Gertrude.

And this time, no one dies.

Maddy Franklin reports on higher ed for PublicSource, in partnership with Open Campus, and can be reached at madison@publicsource.org.

This story was fact-checked by Rich Lord.

This article first appeared on PublicSource and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.