The emotional and unifying power of traditional festivals could only interest marketing. More and more companies are trying to associate their image with a festival like Christmas. Why? What risks do they take by doing so?

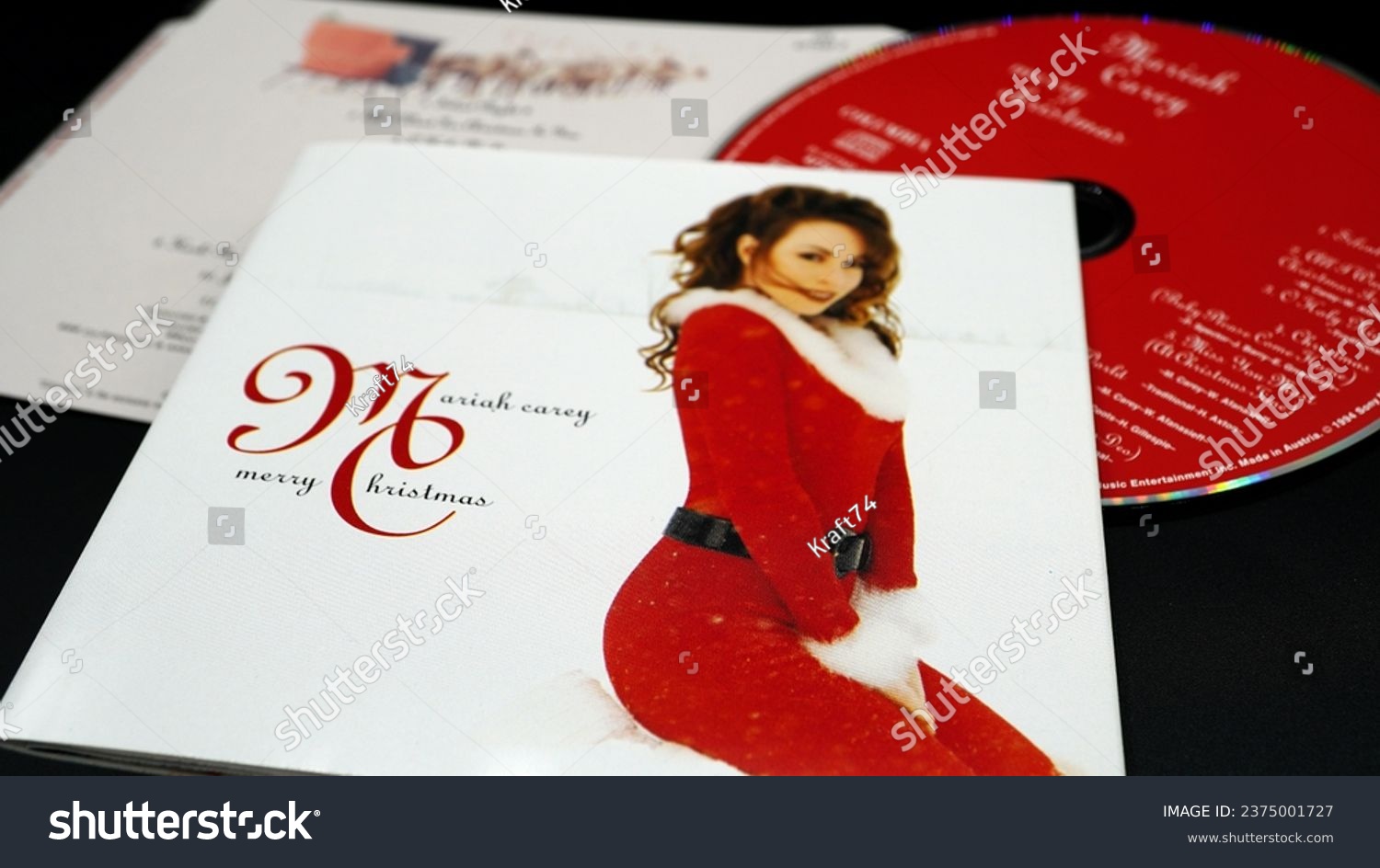

Major holidays, whether religious or cultural, occupy a central place in our lives. However, these celebrations, once centered on symbolic or spiritual values, are now increasingly linked to the consumption of products that have become iconic. Who doesn’t associate Christmas with Mariah Carey these days? Her hit “All I Want for Christmas Is You” has become a staple of the month of December, so much so that Billboard magazine estimated that in 2021, Sony earned around $2.95 million from this single .

This figure clearly illustrates the extent of the commercialization of certain collective celebrations. How did we get here? By what mechanisms have brands transformed collective celebrations? What risks do they take?

When tradition and capitalism meet

Major holidays, whether religious or cultural, are increasingly influenced by corporate marketing strategies that seek to capitalize on their popularity and symbolism. By integrating products into the rituals associated with these holidays – whether it’s Picard’s iced Yule logs, the Bonne Maman Advent calendar or personalized M&M’s for Valentine’s Day – brands seek to create a symbolic and emotional attachment with consumers .

These practices aim to transform simple objects into iconic symbols, as demonstrated by the theory of cultural meaning transfer . For example, by making their iconic golden rabbit a staple of Easter celebrations, Lindt is associated with the values of this holiday, namely joy and renewal. This allows the brand to position itself as a symbol of pleasure and festive celebration, thus anchoring itself in the collective imagination .

Brands at the heart of popular culture

This transformation of products into symbols reinforces the perception of brands as central actors in popular culture. In addition, these rituals, which often connect the past and the present, generate a sense of nostalgia and community. Thus, they also become powerful tools for marketing, as shown by their massive use in Coca-Cola’s Christmas marketing campaigns . However, this commercialization also changes the meaning of the celebrations themselves. When a holiday is associated with products or brands, its collective and symbolic dimension can be eclipsed.

This growing commercialization is partly changing the meaning of collective celebrations, by integrating new rituals focused on consumption. For many people, the consumption of certain products, such as Christmas coffee at Starbucks or Halloween candy from Haribo, has become an integral part of the pleasure associated with the holidays.

Marketers influence not only the location and products associated with consumption rituals, but also the timing of these rituals . For example, seasonal Christmas offerings are advertised well in advance of the holiday itself, and many consumers eagerly await seasonal products that are exclusive to the period . For example, a product like Starbucks’ Pumpkin Spice Latte offered during Halloween contributes to the creation of new rituals. Indeed, holidays associated with specific products create hybrid rituals, combining old traditions with new business practices . While these rituals are often perceived as modern and attractive, they tend to dilute the original meanings of the holidays.

An appropriation without limits?

Brands have been transforming the holiday into a collective affair for a long time: The Hallmark greeting card company played a pivotal role in the early 20th century, making personalized cards a staple of Valentine’s Day . But some companies are now going further, trying (and failing) to turn these celebrations into trademarks.

In 2021, Mariah Carey, dubbed the “Queen of Christmas,” attempted to trademark the title. This attempt to legally appropriate a part of Christmas was met with immediate backlash, both from the general public and from other artists. Elizabeth Chan, also dubbed the “Queen of Christmas” by The New Yorker in 2018 for her Christmas albums, publicly criticized Carey for attempting to monetize Christmas. Chan even filed a lawsuit to block Carey’s trademark application, arguing that Christmas “is meant to be shared, not owned . “

Earlier, in 2013, Disney attempted to trademark the name “Día de los Muertos” (Day of the Dead) to accompany the release of its film Coco . Disney hoped to secure the rights to the Mexican holiday, which is rooted in spiritual and family traditions, for merchandise such as jams, juices, toys, and clothing. But consumers protested on social media, criticizing Disney for its desire to commercialize their cultural heritage. Disney’s move to trademark a foreign holiday was seen as an attempt to erase the spiritual and community meanings of the holiday in favor of purely capitalist logic.

Preserving the essence of the holidays

As we can see, the intersection between tradition and commercialization thus poses a central question: how can we preserve the collective essence of major festivals while allowing them to adapt to a globalized consumer society?

It has been shown that the focus on the material aspects of Christmas celebrations can decrease individuals’ well-being, while family and spiritual activities promote greater personal satisfaction . Yet consumers perceive products offered during the holiday season as authentic as long as they remain aligned with the values they associate with the celebration . It is not about owning these holidays, but about celebrating them, recognizing their central role in collective culture.

The line between respectful participation and pure commercialization often remains blurred. Brands like Coca-Cola at Christmas or Hallmark on Valentine’s Day illustrate this tension. While their initiatives have become iconic, they also raise questions about the balance between preserving cultural values and appropriating for commercial gain. Brands must carefully navigate the line between enrichment and appropriation, taking care not to erase the symbolic meanings that are the lifeblood of these celebrations.