Chairman Fred Hampton Jr. opens up about his father’s legacy, his own revolutionary work, and how the Black Panther Cubs continue the movement today (Photo Credit: Tacuma Roeback).

by Marshelle Sanders, For he Chicago Defender

“I’ve often said I’m a revolutionary living in reactionary times; much of my work involved being on what we call a political pivot—always adapting to the unexpected while staying focused on the mission. It’s a daily grind. But this is what movement work looks like. We stay ready.”

Inside the Hampton House

On a brisk afternoon, Chairman Fred Hampton Jr., Leader of the Black Panther Cubs, walks toward the Hampton House at 804 South 17th Avenue to welcome the Chicago Defender team inside for an interview.

As he steps into the house, already deep in conversation, he calmly prepares the dining room of his father’s childhood home, now a historic site. Despite a packed schedule, he takes the time to make this moment happen.

Inside the notable Hampton House, history lives in every corner. Chairman Fred Hampton Sr.’s spirit can be felt when you walk through the doors.

And at the heart of it all is Hampton Jr.

A Legacy Carried Forward

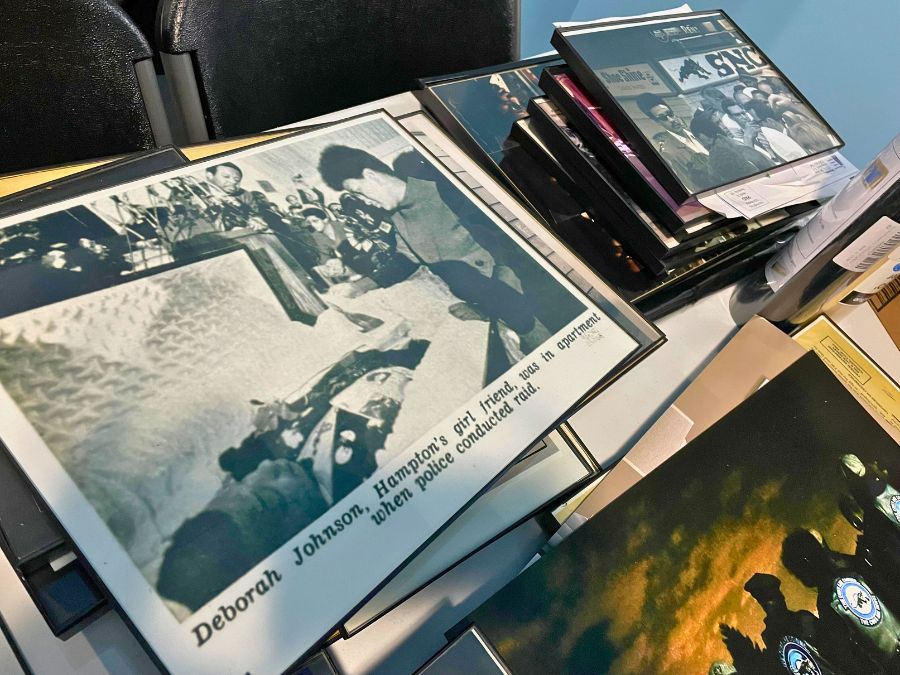

Chairman Fred Hampton Jr. speaks with clarity and sincerity as he shows us some photos, each a testament to effort, survival and radical love. “This one is my mother on the run at the time,” he said, explaining one of them.

The photos and art around the home tell the story of a movement. Looking back, he recalls through testimonies and pictures how many students left school and their careers in the mid-1960s to serve the people after hearing Chairman Fred speak. “They came straight to Chicago and got to work,” said Hampton Jr.

The son reflects on a powerful image of Chairman Fred Sr. with Young Lords founder Cha Cha Jiménez. “I just spoke at Cha Cha’s funeral. He was family. A real comrade.”

The weight of a great man’s life can be a heavy burden for many sons and daughters, but for Hampton Jr., it’s both a privilege and a responsibility.

“It’s not pressure. Its purpose. It’s a comfortable fit—like you’re calling. I feel loyal not just to my father, but to all our ancestors. Once you know, you owe.”

Born into the Struggle

Mural style art of Fred Hampton Sr. at The Hampton House (Photo Credit: Marshelle Sanders).

The story of how Fred Hampton Jr. came into this world is well known: He was inside his mother’s belly when teams of Chicago police raided her and his father’s home. They pumped over 90 bullets into that apartment, instantly killing 21-year-old Fred Hampton and 22-year-old Mark Clark.

The Guardian recently published a series chronicling the lives of the children of Black Panthers, stating that Hampton Jr., born 25 days after his father’s Dec. 4, 1969 assassination, inherited a life “defined by the father whom he never met.”

But somehow, his dad was always there. As a child, he remembers being at a park on 63rd on the South Side, talking to his mother, yet feeling his father’s presence. When he expressed this, she simply nodded, affirming his experience.

As he grew up, he felt compelled to take action, stepping into his father’s legacy with vigilance. From enduring cold winters in Chicago to navigating media deals, Hampton Jr. learned early on to protect the story, not just retell it.

“Many tried to tell my father’s story without understanding the movement’s soul. It had to be honorable.”

The Emotional Cost of Leadership

Photo Credit: Tacuma Roeback

Carrying the weight of a revolutionary legacy isn’t just physical—it’s emotional and spiritual too. “Battle fatigue is real,” Hampton Jr. admits. “There are days I’m completely worn down. But the struggle? It’s my addiction. It keeps me going.”

He reflected on a moment before his trip to Africa when he almost didn’t go. “I was deep in it, man. Tired. But I made myself get up and move. And I came back rejuvenated.”

To stay balanced, Hampton Jr. connects with nature, comrades and silence in rare moments. He also turns to water for rejuvenation. “Sometimes I just need water. Water resets me.”

He mentioned he was imprisoned in the early 1990s on trumped-up charges related to alleged arson, serving nine years of an 18-year sentence. He’s clear: it was political.

“I was taken to prison because of my work. They weren’t asking about fire but about my politics, writings, and affiliations. They knew who I was.”

He’s seen firsthand how the children of revolutionaries often pay the highest price. “I’ve met other Panther Cubs—we grew up under surveillance and trauma. We didn’t get to be children, but we understand the assignment.”

He recalls a recent court support visit where a public defender said, “I saw your story. And it moved me.” That, he believes, is the power and price of truth.

What Movement Work Looks Like Today

Fred Hampton Jr. with Chicago Defender reporter Marshelle Sanders (Photo Credit: Tacuma Roeback).

Hampton Jr. laughs a little when asked what a typical day looks like. “A day? It’s rarely typical.”

On any given day, he might receive an urgent call about court support— quickening to stand in solidarity with someone who’s been behind bars for decades, often unjustly.

Sometimes I’m outside Hampton House, ensuring the community fridge is stocked. Other times, I’m catching last-minute flights to speak on behalf of political prisoners or tapping in with associates in places like New Orleans, Minnesota, or Brazil.”

The movement isn’t limited to one block or one city. “Sometimes I live out of a suitcase,” he says. “Duty calls.”

Central to the work of the Black Panther Party Cubs is Triple C’s program—Children, Community, and Cubs—which runs every Saturday in cities worldwide.

“We not only just hand out food and help with valuable resources. We politicize,” he said. “We feed the body and the mind. We discuss political prisoners, health disparities, and violence in our neighborhoods. And we go where others won’t.”

Another initiative, Retreat from Chiraq, brings youth from the city to a friend’s farmland about 45 minutes outside Chicago, offering them a space to breathe, reflect, and reset away from the pressures of urban life.

“It’s like a before-and-after commercial,” Hampton Jr. laughed. “Kids come out glued to their phones, then the next thing you know, they’re feeding chickens and learning about agriculture. That’s revolutionary.”

The Panthers might’ve worn leather and berets, but the Cubs know how to blend that with hoodies and headphones. “We meet the youth where they are,” he said. “The street is our office. Hip hop is our tool.”

From barbershops to rap studios, they engage with young people directly. “Minister Huey P. Newton said, ‘Power is the ability to define phenomena and make them act in a desired manner.’ So, if hip hop is a phenomenon, we define it. We use it.”

This community-based strategy includes Free Em All Radio, a weekly radio show at Intellectualradio.com.

They’ve also been actively campaigning to reclaim the vacant lot at 54th and Halsted in Englewood—the former site of Chairman Fred Hampton Sr.’s Uhuru house until the early 1990s.

“We’re still at war—not just with guns and tanks, but with psychological warfare, media attacks, and cultural genocide. We fight it all.”

When Hollywood Came Calling

“Judas and the Black Messiah,” directed by Shaka King and produced by Ryan Coogler, debuted in February 2021. It brings the life and assassination of Chairman Fred Hampton Sr. to the big screen. Before filming began, key conversations were held inside the Hampton House.

Chairman Fred Hampton Jr. recalls one meeting around the dining room table—where he, Coogler, and others sat to decide whether to proceed with the film. “That decision wasn’t easy,” he said, reflecting on the weight of preserving his father’s legacy with integrity.

Chairman Fred Hampton Jr. recalls the early meetings about Judas and the Black Messiah as a fight to protect the truth.

He also pushed back on false narratives, especially about William O’Neal, the FBI informant. “O’Neal was never Chairman Fred’s actual security—that’s propaganda. The Panthers had structure, discipline, and process; the Party was always peaceful and coordinated, which still stands today.”

Even during production, he and other Panthers traveled to different film sets to keep the movie grounded in truth. “We had to make sure it didn’t get romanticized. We needed to see the challenge, the betrayal, that’s why it’s called Judas.”

He credits Ryan Coogler as a major influence on the project, praising his discipline and leadership on set. Hampton Jr. described Coogler as focused and grounded, always carrying himself with purpose—leading each day with a clear respect for the Black Panther Party and its principles.

From Legacy to Living Movement

Photo Credit: Tacuma Roeback

The Hampton Jr.’s work is a continuation of his father’s legacy—it’s a living, breathing movement. Through initiatives like the Triple C’s (Children, Community, Cubs) and collaborations worldwide, the Black Panther Cubs are bringing political education, free breakfast programs, cultural organizing and revolutionary analysis to youth across the U.S. and internationally.

Chairman Fred Hampton Jr. is looking forward to the renovation of his father’s home in Maywood, transforming it into a vibrant community hub. The space will reflect the values of the Party and serve as a center for culture and activism. A Tiny Desk-style collaboration is also in the works with Chicago-based spoken word artist K-Love the Poet, further connecting art with movement work.

He is also hopeful about creating a garden space area and collaborating with the community to reopen the Fred Hampton Aquatic Center at 300 Fred Hampton Way in Maywood.

But during our interview, he took a moment to also comment on one other little-known comparison with his father.

“People don’t know, but I dance like my father. I like stepping, but I tell people to take it easy on me (laughs). My mom used to joke, ‘You dance just like your dad, Chairman, ya’ll got no rhythm.’”

Yet, what also binds father and son is the thing that ultimately propels the latter to continue the former’s legacy.

Quoting Field Marshal George Jackson, Hampton Jr. closes with a motto:

“We fight for the unborn, the living, and the dead. It’s not only about my legacy,” he said. “It’s about the people. The people who aren’t born yet. The ones who don’t know they aren’t Panthers yet. The ones waiting on a spark.”

And Chairman Fred Hampton Jr. is making damn sure that spark stays lit.

This story is part of #CD120, a yearlong celebration of The Chicago Defender’s 120th anniversary, where we honor our legacy by telling stories from our history—past and present—rooted in Chicago, resonating far beyond.

This story was also made possible in part by the groundbreaking reporting of journalist Ed Pilkington and our colleagues at The Guardian. We encourage readers to explore Pilkington’s powerful feature, “Radical Change Isn’t Free,” and the companion documentary The Black Panther Cubs: When the Revolution Doesn’t Come at: theguardian.com.