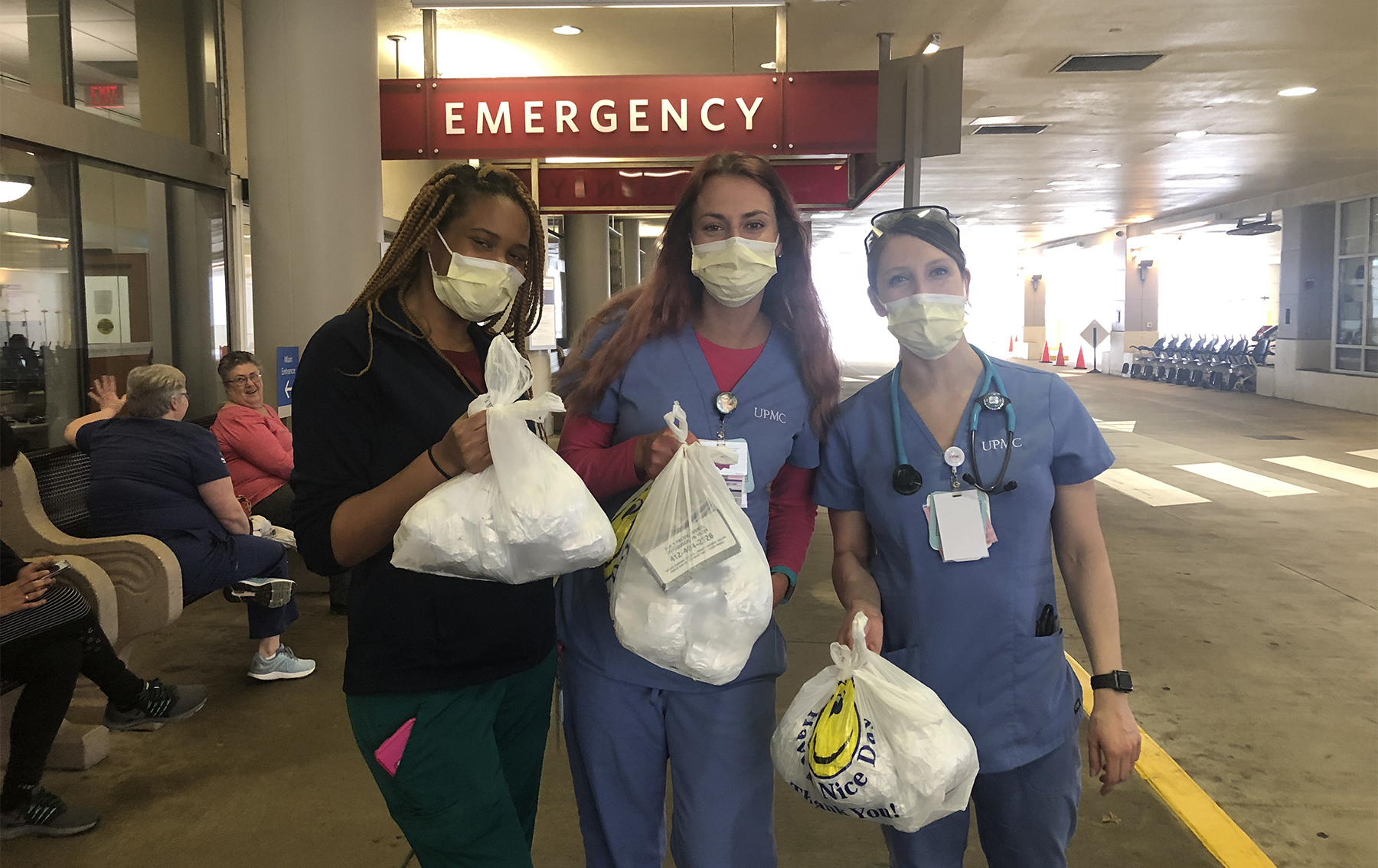

PHRESH team data collectors Symone Turner (left) and Arneta Dyer at the Hill District field office. (Photo credit: Joshua Franzos)

In 2010, a University of Pittsburgh and RAND research project called PHRESH (short for Pittsburgh Hill/Homewood Research on Eating, Shopping, and Health) began a study. They wanted to learn how the upcoming opening of a new grocery store in the Hill District — the first in over 30 years — might affect Hill District and Homewood residents’ shopping habits and diet.

To better understand these issues, University of Pittsburgh’s Dr. Tamara Dubowitz, Professor and Chair of Epidemiology in the School of Public Health and former RAND senior policy researcher, and her team chose the two neighborhoods. The Hill District and Homewood were similar in income and population, which would make it easier to study things like diet, weight, and shopping habits, as well as how people felt about their neighborhood after a grocery store opened in one of them.

Dr. Tamara Dubowitz (Photo credit: University of Pittsburgh)

Tamara and her team selected 900 Hill District and 400 Homewood households. They opened a field office in the Hill District and hired and trained local data collectors (DCs). DCs were trusted people from the community who began knocking on household doors and encouraging people to join the study.

Regularly, DCs gathered information through in-person surveys, spending time in people’s homes asking questions, listening to responses and concerns, and sharing in participants’ lives.

This first PHRESH study was created in response to U.S. obesity rates. According to recent statistics, in most states the rate is 40% for Black adults compared with 35% for white adults. Obesity is linked to higher rates of asthma, cardiovascular disease, certain types of cancers, diabetes, and osteoarthritis.

“Food deserts” in underserved communities contribute to the higher obesity rate. Food deserts happen when there’s no easy access to affordable, nutritious food like fresh fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. Food deserts are another result of structural racism, including red-lining.

After gathering data before and after the store opened, researchers learned that Hill District residents shopped at the new grocery store. They felt better about their neighborhood since the grocery store opened. However, some residents still shopped at other grocery stores farther away where prices were cheaper. There were health improvements among Hill District residents, but no clear link between shopping at the new grocery store and healthier eating habits.

During that year, other infrastructure changes were happening in the Hill District. A new company brought in training, jobs, and business support. New green spaces were added along with better housing and community centers. While all this positive activity made it harder to determine the single impact of a new grocery store, it offered new opportunities to study other things.

Today, PHRESH has grown to include six separate studies (so far). Each study looks at how neighborhood investments and improvements in infrastructure — which includes parks, businesses (like grocery stores), housing, schools, libraries, community centers, and more — impact people’s health outcomes.

Many of the studies include community events that invite residents to learn more about specific health conditions. The latest study is called THINK PHRESH. It focuses on how neighborhood changes throughout a person’s lifetime affect how they age, especially their memory and thinking skills.

THINK PHRESH includes community events that raise awareness, reduce stigma, and help people learn about Alzheimer’s disease and dementia, especially how important it is for caregivers to take care of their own mental health.

Like the first PHRESH study, the newer studies depend on members of the community to answer questions and offer ideas and concerns about infrastructure changes and how those changes affect their physical and mental health.

For example, do housing improvements impact sleep apnea? Do safe green spaces change people’s physical activity? What’s the relationship between health conditions (like diabetes, high blood pressure, and obesity) and mental health conditions (like anxiety and depression)? Does wet weather and flooding affect people’s well-being at home in terms of moisture levels, air quality, and sicknesses from viruses and bacteria?

La’Vette Wagner-Battle (Photo credit: Joshua Franzos)

La’Vette Wagner-Battle, who has a master’s degree from Chatham University, has been leading the PHRESH field office in the Hill District since startup. A lifelong Hill District resident, La’Vette is loved and respected by researchers, collaborators, and participants alike. She loves her neighborhood, her neighbors, and her job equally. “People in the neighborhood — who can be skeptical about healthcare — ask me if they can join the study,” she says laughingly. “They want to participate because PHRESH gives them a voice in the health of their community and with that voice comes a sense of pride in their neighborhood.”

Dr. Andrea Rosso agrees. Andrea is Associate Professor of Epidemiology at Pitt, the leader of the department’s Brain, Environment, Aging, and Mobility (BEAM) lab, and a PHRESH investigator. She notes, “If people feel like they — and their community — matter, there’s hope.”

Dr. Andrea Rosso (Photo credit: University of Pittsburgh)

After 15 years and six studies what have PHRESH researchers, collaborators, participants, and residents learned so far? Is there one thing that stands out as a kind of tipping point for better health outcomes in underserved communities?

“There’s no magic answer,” says Dr. Dubowitz. “Instead, the research clearly shows that health outcomes improve when infrastructure investment is based directly on input from the people who live in the community.”