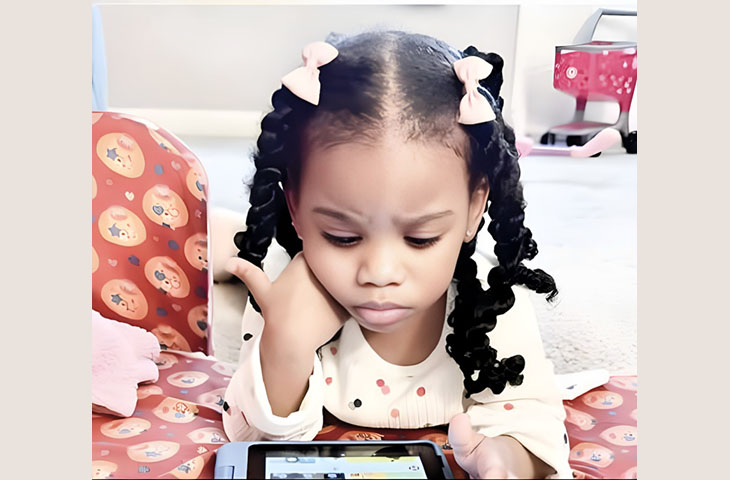

Anthony Tilghman’s daughter was just 1 year old when he and his partner decided to seek answers about a few concerns they had in terms of their child’s early development.

“We noticed when she was maybe 1, that she wasn’t really talking. She just would say these little one-liners a lot. We were working and hoping it would eventually change, but we started to assume that she had a little developmental delay in her reactions,” said Tilghman, Ward 1 commissioner for District Heights, Maryland, and social media manager for The Washington Informer.

Eager for answers, Tilghman and his partner requested testing from a primary care physician who simultaneously suggested sending their daughter to a specialist for further review. After a year-long wait to be seen by the proper physicians, his daughter was officially diagnosed with mild autism.

Diagnoses of autism spectrum disorder, a neurological and developmental disorder that impacts how people learn, communicate, interact with others, and behave, has increased across children in the United States, seeing significant spikes today versus 30 years ago.

As April is Autism Acceptance Month, Tilghman is one of the many people around the nation and globe working to raise awareness of the disorder and help families in accessing resources and support once navigating an autism diagnosis.

“[Once] you get diagnosed, you can reach out to a speech therapist and a developmental therapist, so the support is definitely there,” Tilghman told The Informer. “We signed up for all of the support services that’s really needed now to improve that functionality and those areas of concern for her.”

Just a few months shy of her third birthday, Tilghman explained the chain of support that has come after his daughter’s diagnosis, in conjunction with early schooling, has brought visible improvement in her development skills.

“She loves school. School is probably the best thing for her,” he said. “We were really hesitant to put her in school, a little nervous. But, she has really improved in her comprehension, and talking through being around the kids.”

Autism Statistics and Symptoms, Addressing the Disorder

Autism spectrum disorder occurs across all racial, ethnic and socioeconomic groups, and is not a one-size-fits all diagnosis.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “roughly 1 in 31 (3.2%) of children aged 8 years has been identified with autism spectrum disorder” and is three times more common among boys than girls.

Autism consists of varying tiers on a spectrum.

Some individuals have a mild level of the disorder, managing to be completely self-sufficient and engage in social interactions. Many of these individuals can be extremely well-versed in specific fields, allowing them to foster a completely normal and independent life.

However, individuals on the other side of the spectrum sometimes never develop full speech, grow to have severe developmental and behavioral disorders, and lack key social skills in order to effectively interact with others.

Many children show symptoms of autism by 12 to 18 months, or even earlier.

Early signs of autism in children can vary, but Dr. Paola Pergami, a pediatric neurologist at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, shared some of the key symptoms that signal autism disorder in young children.

“Generally, there is a lack of speech development or regression of speech. So, they start saying a few words, and then they regress, and they lose those words,” Pergami told the Informer. “[Also] the difficulty with social interaction. Instead of interacting with other kids, they just play on their own. They go grab a toy [and] don’t pay attention if anybody else was playing with the toy, and they play on their own. They never interact with kids.”

In addition, Pergami said some children with autism can display repetitive behavior with toys, be very intentional about having things a certain way, and show resistance when moving them from what they want. Additionally, children with autism often show very specific sensitivities to texture, particularly seen in choice of foods, or even the texture and feeling of certain clothes.

“It’s mostly the social and sensory abnormalities that are visible, and then the lack or delay of speech development.”

Recently, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) cited the CDC’s findings of autism prevalence in the country increasing from 1 in 36 children to 1 in 31.

Newly minted HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. expressed concern over increasing autism rates.

“The autism epidemic is running rampant,” said Kennedy,” who has been known to correlate autism diagnoses in children with required vaccines, without medical evidence to support his claims. “We are assembling teams of world-class scientists to focus on research on the origins of the epidemic, and we expect to begin to have answers by September.”

However, leading autism organizations such as the Autism Society of America, Autism Speaks, Autism Self Advocacy Network have pushed back on Kennedy’s plans, coming together to release a joint statement calling for “evidence-based approaches and increased investments in programs that serve the autism community.”

“We are deeply concerned by growing public rhetoric and policy decisions that challenge these shared principles. Claims that autism is ‘preventable’ is not supported by scientific consensus and perpetuate stigma,” the organizations wrote in a statement. “Language framing autism as a ‘chronic disease,’ a ‘childhood disease’ or ‘epidemic’ distorts public understanding and undermines respect for autistic people.”

While challenges for birthing people, such as drug use or vitamin deficiency, are often correlated with children later diagnosed with autism, Pergami debunks many of the theories people have about the roots of the disorder, based on proven studies and her personal expertise.

“I don’t think that any study has ever shown any environmental factor, ever. They think that we know for sure that vaccines do not cause autism,” she told The Informer. “It was demonstrated that there is really no connection. It has never been proven.”

Disparities in Autism Diagnoses, Increasing Access to Care

Among children documented with the disorder, autism prevalence is reported to be the lowest among non-Hispanic White children, and higher among Black, Asian or Pacific Islander, and American Indian or Alaska Natives.

Despite the statistics suggesting more concentrated diagnoses among certain demographics, Dr. Pergami finds the rates to be directly reflective of the quality of access to care among communities.

“I think [the issue] is access to care. I don’t think people are different. In D.C., I actually see people with autism for their initial diagnosis, because without diagnosis, they cannot access services,” Pergami explained. “Some kids are diagnosed early properly. If the parents are educated, they have access to care, and they can express their concerns and so on. And those kids, if they have a severe problem, they do well because they access service early, or they do as well as they can.”

Having witnessed the detrimental effects of delayed diagnosis with close family members, Tilghman said that he felt compelled to address his daughter’s autism concerns early.

“I think that’s a common thing we see sometimes among African Americans. We really wait until the last minute to get help,” Tilghman told The Informer. “We’re more reactive, we’re really not proactive when it comes to our health, and that’s one thing that I wanted to change with my daughter.”

Early intervention for autism is crucial, as it maximizes a child’s potential for development and learning, especially during the brain’s most receptive period.

Upon Tilghman’s request for his daughter’s testing, he and his partner were referred to seek further help through Autism Speaks, a nonprofit organization dedicated to promoting solutions for individuals with autism and their families.

While they were able to get their daughter the testing she needed, the couple had to commute to Virginia from Prince George’s County for the family to get the support they needed.

For many families residing in certain areas around Prince George’s County and Washington, D.C., transportation as well as a lack of health education can present as a challenge preventing patients from getting necessary help, care and resources.

“There’s not enough support,” said Tilghman. “I think it’s kind of like trying to find a Black therapist. If you need help, you have to find a specialist that’s in that specific area of support. And finding those people here is like trying to find a needle in the haystack.”

While Tilghman and his family are fortunate to be able to access the resources needed for his daughter to thrive, he emphasized the importance of local leaders advocating for and investing in greater autism health resources.

“We lack resources for things that we need in our immediate area. You have to travel outside the area to find certain services, but yet, we have numerous Royal Farms or similar types of businesses,” Tilghman said. “We are put in situations where we have a lack of resources based on the people that control that area, because they tell us what’s good for us. They go by what brings in the money. They don’t really go about what’s great for accessibility in our community.”