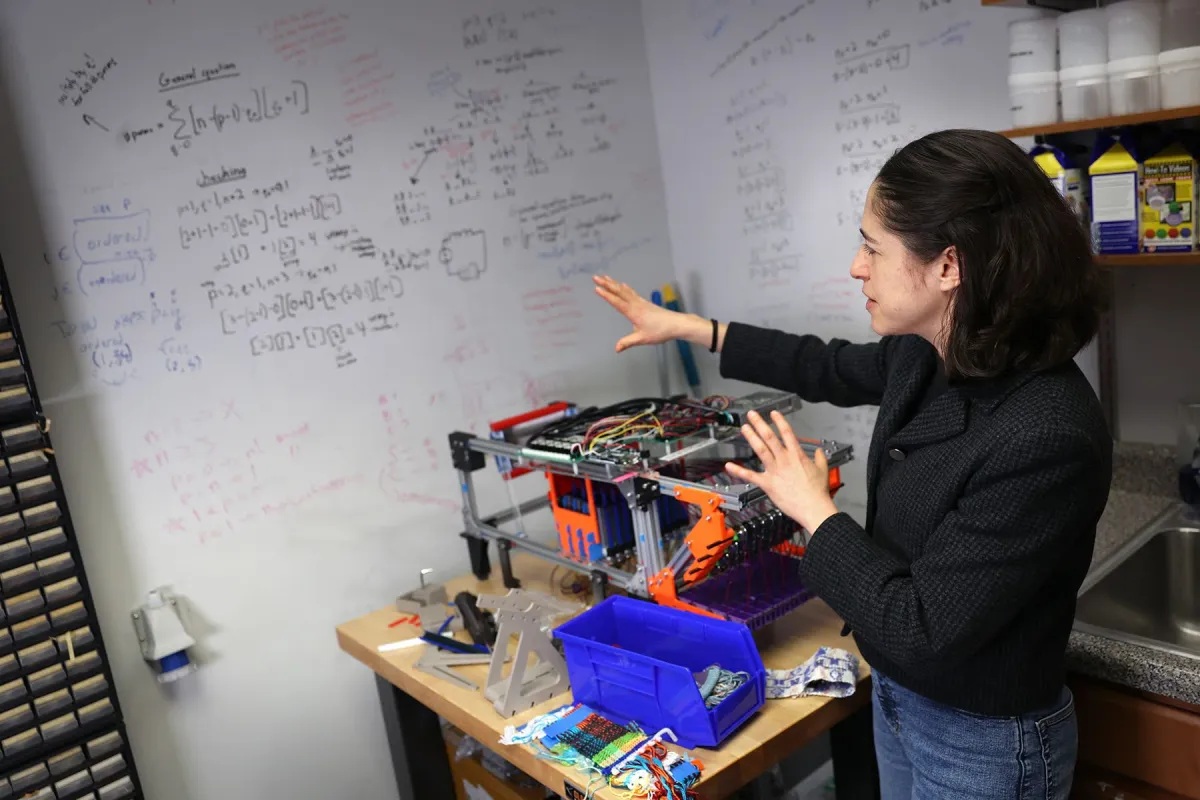

Melisa Orta Martinez explains the math on the whiteboard on Tuesday, March 18, 2025, at her SHRED Lab at Carnegie Mellon University in Oakland. (Photo by Anastasia Busby/PublicSource)

My journey from humiliation at the Model U.N. to a top research institution wasn’t straightforward, but the message is clear: When they laugh at you, push even harder.

“PublicSource is an independent nonprofit newsroom serving the Pittsburgh region. Sign up for our free newsletters.”

As a robotics professor, I meet many talented and driven students who have dreamt of robotics since childhood. I sometimes wish that I could say “I have been building robots since I was five” like many student application essays I read. But the truth is that my path was forged by a series of fortunate and unfortunate events which ultimately, and with a lot of help, brought me to design everything from a robotic loom that integrates math and art, to a mouse for blind individuals and even robots that assist in earthquake rescues.

Growing up in Mexico, my dreams were anchored not in robots but in the profound, urgent needs of my country. I imagined a path toward enacting change by becoming a delegate to the United Nations, resolutely addressing those powerful nations whose insatiable hunger for illicit substances, indifferent gun laws, selective environmental protections and imbalanced trade policies cascaded downward, burdening the lives of people in the developing world.

Driven by this vision, I studied diligently and, during high school, I found myself fortunate enough to journey to New York City, attending a Model U.N. conference. I was chosen to participate in its most prestigious committee — the Security Council. Gathered there were brilliant students from around the globe, high achievers born into spheres of immense privilege and influence, perfectly positioned, I believed, to rewrite history.

Seizing the moment, I delivered impassioned speeches. After all, this was just a simulation — what did we have to lose? “Let us pass historic resolutions! Global disarmament! Ecology above economics! We must care for everyone!”

My calls were met by silence and cool indifference. “It’s not realistic,” they said. “It would never happen.” More devastating than their rejection was the sudden clarity of my own naïveté. They understood the consequences of their privileged world, and yet, they remained unmoved.

Back then, I was upset and frustrated. Years later, I realized something important that I often remind myself and others: While it’s unfair that someone experiencing injustice should have to shoulder the responsibility of initiating change, no one else may feel motivated to do so.

Failing superbly

Feeling rejected, my next step came by another weird circumstance during high school. Our computer science teacher tasked the class with building an automata algorithm (basically, a diagram that could solve a problem posed to it). They said if we could solve the problem, we should consider a career in computer science. I remember being so proud I solved it, but when I presented it to the teacher they dismissed me: “Well, but it doesn’t matter, you are a girl.”

That sealed my fate. I was going to be a computer scientist. I was going to study hard, become successful, and then open schools in Mexico. Schools that advanced Mexicans, so that we did not need to go to the U.N. and tell the first world to stop their practices. We would lift ourselves up and stop them ourselves.

So I switched my concentration in high school from literature to math, and I went to college to study computer science. And I failed, superbly.

I did not consider that my peers had a deeper interest in the subject than just proving a teacher wrong, and that they knew what they were doing. I could not keep up. Everything was new to me, kids laughed at me and eventually I dropped out.

Luckily and surprisingly, I did not consider myself stupid. Even though I had failed thoroughly, I convinced myself that what I needed was to pursue something harder, so I switched to electrical engineering. This new path had its own set of challenges: I had professors hit on me or even openly hint at bribes (thankfully, I was too oblivious to notice), and once, a landslide nearly caused me to fail a class. On the other hand, electrical engineering was a small major at my college, and most of us hadn’t even touched a circuit before. In that environment, I did well, thanks to some professors who generously supported and mentored me.

Through my college experience, I learned that hard work matters — but it’s rarely enough

on its own. True success depends greatly on the help and kindness we receive from others, plus sheer luck.

Thanks to my own stores of help and luck, I eventually landed an internship at a laboratory in Germany, where my journey into research started. It was a completely new and bewildering experience. People actually spent their time just inventing stuff? Seriously? And sometimes these inventions weren’t even immediately useful?

Coming from a world ruled by companies that rarely thought beyond next quarter’s profits, I was amazed to discover researchers who dared to look decades into the future. Imagine studying something now that might become a cure for cancer in 20 years! That sounded completely crazy — and exciting — to me, and I desperately wanted in.

My diversity became an asset

Somehow, against all odds, I applied and got accepted into Stanford University for a master’s degree in electrical engineering.

Stanford was hard. I wasn’t remotely prepared for it.

Part of it was culture shock. I had never experienced such a fiercely competitive environment. I’d faced challenges before, but it always felt like students versus institutions, not students competing against each other. For the first time in my life, my peers openly and repeatedly suggested I wasn’t good enough. To be fair, they had a point; my education wasn’t on par with their elite schooling. Yet, amidst all the stress and doubt, I slowly realized I had something unique to offer. My approach was different; I saw problems from alternative angles and generated unconventional ideas. These experiences taught me that my different background could actually add value.

My Ph.D. was just as chaotic as the rest of my academic journey: more struggles, more catching up and even stranger experiences — like getting fired from a startup I co-founded and being robbed and thrown down the stairs by an acquaintance. I would fall asleep to the sound of gunshots, only to wake up to frustrated emails from my advisor because I’d missed a deadline for proofreading a proposal. She was justified in her frustration, she didn’t need someone with my particular complications. Between my Mexican background, language challenges, visa and travel restrictions, a weaker academic foundation compared to my peers, and having a sick dog and cat that disqualified me from campus housing, my advisor had plenty of reasons to replace me.

However, she stuck by me. It wasn’t easy for her, and I will be eternally grateful to her. She gave me the opportunity to learn how to do research and introduced me to many diverse and wonderful people, helping me on my way to becoming a professor and eventually dictating my own research agenda.

The alternative? Missed opportunities

What began as a means to earn money to return home and open schools evolved into a wacky journey, revealing to me numerous other populations underrepresented in science and technology. Inspired by these experiences, my work now is centered on developing engineering solutions aimed at bridging this gap. From designing engineered systems to leading robotics workshops in community centers and carefully choosing the students I mentor, every action I take is driven by my commitment to promoting diverse representation and closing gaps in STEM.

Diverse representation means more than just recognizing ourselves as scientists or seeing people like us in scientific roles. It means actively bringing the voices and needs of diverse communities into our work. Designing from multiple perspectives ensures we don’t overlook the needs of underrepresented populations.

When science and technology embrace true diversity, we prevent critical oversights — like women’s heart attacks going misdiagnosed due to research historically conducted by men, on men. We create infrastructure and services that benefit everyone, not just a privileged few. We inspire novel solutions born from rich, varied insights. Throughout my academic and professional life, I’ve seen repeatedly that the most effective solutions arise from diversity of thought. This truth is continually validated by research.

If you’re on a similarly wacky journey, remember all the help you received along the way and remain humble, be grateful, pay it forward — and keep going. I have failed more times than I can count, and can say from experience that it’s perfectly fine if your goals change. Success takes many forms, and if we keep advocating for diversity, equity and inclusion, we can all be granted the opportunity to contribute.

Melisa Orta Martinez is an assistant professor in the Robotics Institute at Carnegie Mellon University, where she leads the Social Haptics Robotics and Education [SHRED] Laboratory. She can be reached at mortamar@andrew.cmu.edu.

This article first appeared on PublicSource and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.