The impact of fatherhood in the lives of our Black sons must never be understated, and should always be uplifted and celebrated in the African-American community.

Few examples are more powerful than the influence NBA megastar LeBron James and pro football Hall of Famer Deion “Primetime” Sanders have had on their respective sons, Bronny James and Shedeur Sanders.

That influence made headlines last year when the NBA’s Los Angeles Lakers, following Lebron’s wishes, drafted moderately talented Bronny James in the second round, and last week, when the NFL’s Cleveland Browns selected Shadeur Sanders late in the pro football draft, even though his father insisted he was a sure-fire, first-round star.

As a former pro basketball player, I never believed that Bronny James’s athletic résumé — averaging 4.8 points and 2.1 assists per game in one season at the University of Southern California — warranted serious consideration for an NBA draft spot, let alone one with the Los Angeles Lakers, arguably the most iconic franchise in sports.

Maybe it is personal: the Lakers drafted me following my standout season at Villanova University 25 years ago. Or maybe it is because I respect the grind — and the countless players without famous, powerful fathers who clawed their way into the best basketball league in the world — that I just couldn’t stomach it.

I’d seen too many guys fight for a handful of roster spots, only to get that dreaded tap on the shoulder during preseason, followed by the words no player wants to hear: “Coach wants to see you in his office.”

We all knew what that meant. They were getting cut.

I couldn’t agree with LeBron James’s claim that his son was better than many current NBA players while he was still a freshman riding the bench at USC. And I’ll never fully embrace the idea of nepotism, even when some in the Black community see the James family claiming power in a world that has never favored people who look like us.

The athlete and competitor in me just can’t seem to accept seeing it in sports.

Yet, because Bronny James has so far navigated his opportunity with precision, and has carried himself with the grace and professionalism of an NBA veteran, I have had to ask myself, “How can you not root for this kid?”

Now contrast that with the Sanders family.

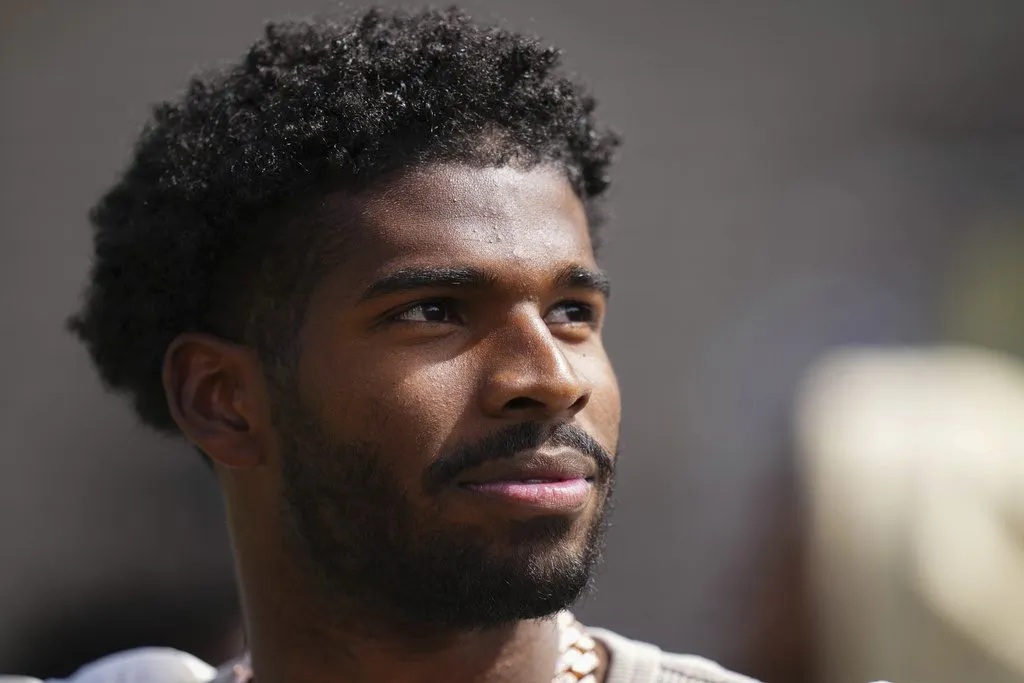

Shedeur Sanders has unquestionably earned his shot at the pros: as a senior quarterback, he led the University of Colorado to a 9-4 season, threw for 4,134 yards and 37 touchdowns. He won both the Big 12 Offensive Player of the Year and the Johnny Unitas Golden Arm Award.

Media analysts, some NFL scouts and Deion Sanders himself — Colorado’s head coach, and the only head coach his son has ever known — declared Shadeur Sanders was a first-round pick; some ranked him as the second- or third-best quarterback in the entire NFL draft class. And Shadeur Sanders seemed to believe the hype, spending tens of thousands of dollars on a custom-built “draft room” for his spotlight moment.

Yet the young man slipped, shockingly, from the first to the fifth round, causing a news and social media uproar. Critics accused NFL owners of collusion, intentionally humbling father and son for being unapologetically confident and powerful Black men.

For those of us who resisted rushing to judgment and looked beyond the surface, a more complex picture began to emerge.

Multiple news reports suggested that Shedeur Sanders came across as brash, entitled and arrogant during pre-draft interviews with teams. Some claimed he arrived at meetings with his own camera crew, rubbing many NFL executives the wrong way.

At the NFL Combine, Shedeur reportedly gave scouts an ultimatum: “If you’re not trying to change the franchise and culture…don’t get me.”

It was a bold strategy, particularly for a player whose résumé, while strong, wasn’t exceptional by NFL standards. It didn’t help that Deion Sanders reportedly attempted to manipulate which teams could draft his son.

The Difference Between the NBA and NFL

It’s also important to remember that the NBA and NFL are two very different leagues.

The NBA tends to be more progressive and diverse, especially in its front offices, creating more space for individual expression and star-driven narratives. In contrast, the NFL has a more rigid, top-down structure. Teams come first, and anyone who challenges that order — no matter how talented — risks being quickly shown the door.

Some may see what I am saying as “respectability politics,” demanding that a confident young Black man conform to the norms and expectations of the dominant culture. I am not suggesting that Shadeur Sanders should have bowed or submitted to every whim of the NFL.

Still, if you want to secure a paycheck — or “the bag” — from a league that expects quarterbacks to carry themselves with more tact and less bravado, you need to do your homework.

When he dominated the NFL, Deion Sanders wore more gold chains than Mr. T, and once told a reporter that if the lowly Detroit Lions had drafted him, he would’ve asked for so much money the team would have had to put him on layaway. He moved how he moved, and there was nothing anyone could do about it because of his off-the-charts talent. Shedeur will probably begin his career as a backup in the league, so being a chip off the old block may not work in his favor.

For those who believe that strong, confident, assertive and unapologetic Black men are often feared in America, in most cases, you are right. But in sports, many times it is celebrated — if you can walk the walk as well as you talk the talk. Yet, sometimes we have to reconsider what we view as strong in our community.

The Philadelphia Eagles’ Jalen Hurts is a Super Bowl champion quarterback with a fat contract and a diamond stud in his ear. But at the University of Alabama, his coach benched him in a nationally-televised championship game, then replaced him the following season — Hurts’ senior year.

Experts doubted he would succeed in the NFL.

But Hurts put in the work, and in five short years was named MVP in his second Super Bowl appearance. He is strong, unapologetic and confident without the arrogance and entitlement that might have worked against him as a pro quarterback.

In the end, Bronny James and Shedeur Sanders both possess the guidance, genetics and support to succeed in whatever they pursue. At its core, they’re simply playing a game — but how they navigate that game will ultimately define them.

The question is: which game are we talking about?

John Celestand is the program director of the Knight x LMA BloomLab, a $3.2 million initiative that supports the advancement and sustainability of local Black-owned news publications. He is a former freelance sports broadcaster and writer who covered the NBA and college basketball for multiple networks such as ESPN Regional Television, SNY, and Comcast Sportsnet Philadelphia. John was a member of the 2000 Los Angeles Lakers NBA Championship Team, playing alongside the late great Kobe Bryant and Shaquille O’Neal. He currently resides in Silver Spring, Maryland, with his wife and son.

This article was originally published by Word in Black. The original story can be found at this link: https://wordinblack.com/2025/05/bronny-james-made-it-shedeur-sanders-almost-didnt/