(Illustration by Natasha Khan Vicens/PublicSource)

The county cited law enforcement safety concerns as it argued to open records officials that it should redact more names than ever before from public salary data.

“PublicSource is an independent nonprofit newsroom serving the Pittsburgh region. Sign up for our free newsletters.”

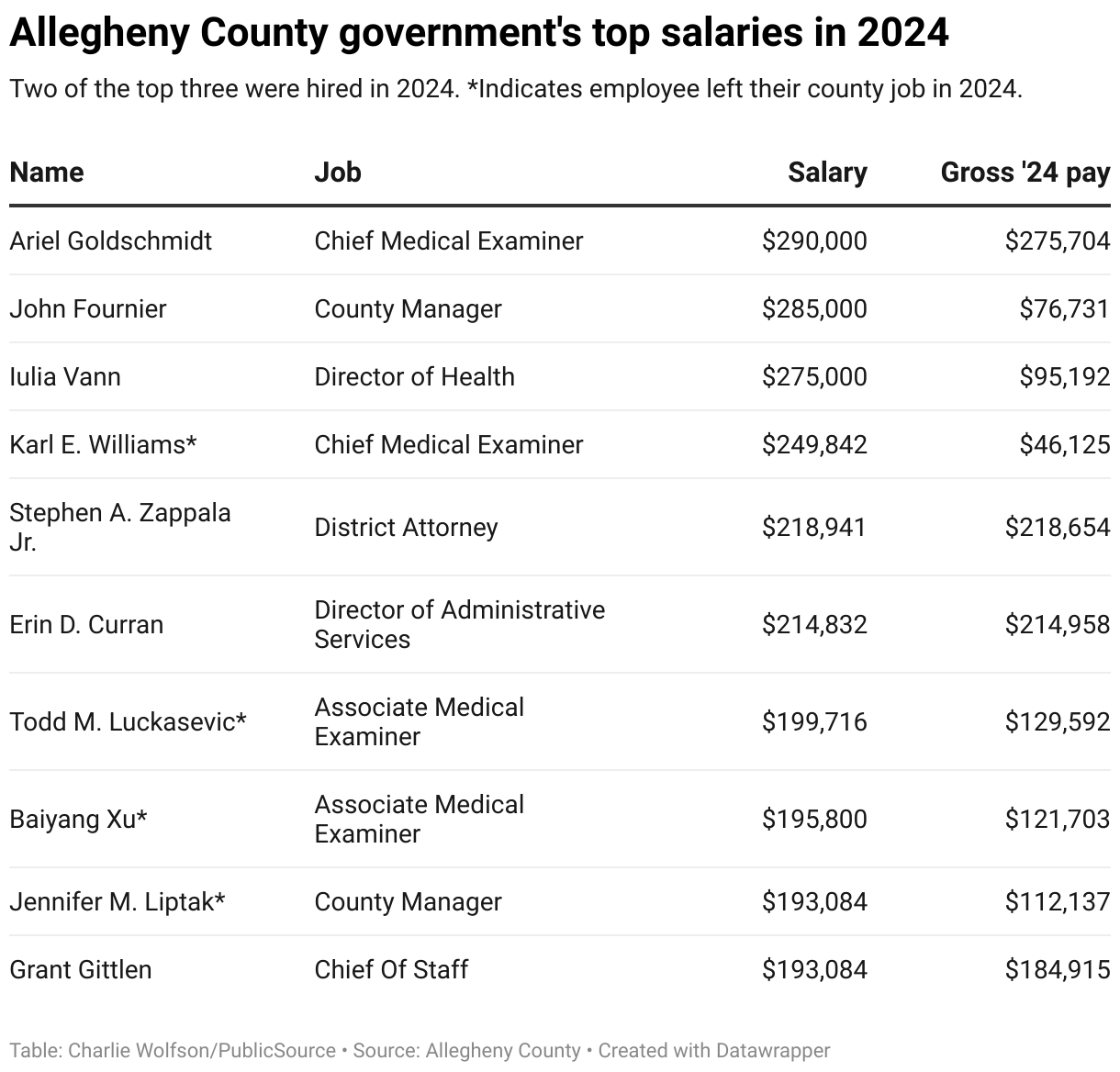

Allegheny County government had a new highest-paid employee last year. Ariel Goldschmidt, the county’s chief medical examiner, took home $275,703 in 2024, according to salary data published by the county.

Goldschmidt took over the top spot in April and earns an annual salary of $290,000 in the role, which is appointed by the county executive.

Click here to view the complete data set.

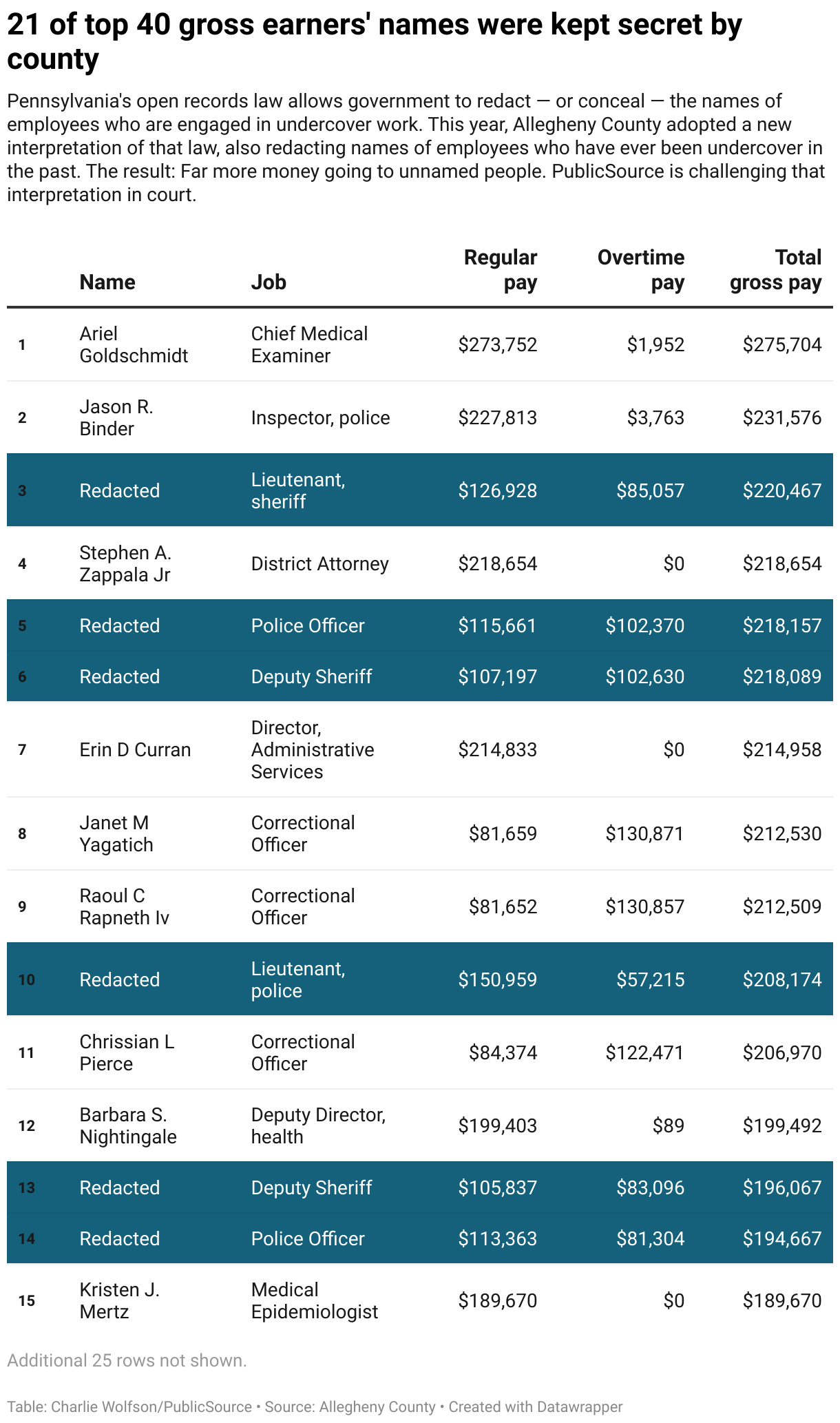

The identity of the county’s third-highest gross earner (factoring in overtime pay), and those of more than half of the top 40 gross earners, are a mystery. The county redacted their names from public data because they are or have been undercover law enforcement agents.

The redactions are part of an expanded interpretation of the state’s open records law taken by the county. The law permits government agencies to conceal names of employees “performing an undercover or covert law enforcement activity” from records provided under the Right-to-Know Law. In the past, the county only redacted names of employees currently undercover. This year, the county began redacting names of anyone it says has ever been undercover.

One result of that move: Far more taxpayer money is now shielded from public scrutiny.

PublicSource appealed the county’s redactions to the state Office of Open Records [OOR], and argued that the Right-to-Know Law only exempts current undercover personnel — not past ones. Though the office ruled in PublicSource’s favor in a similar case last year, the OOR sided with the county this time. PublicSource is appealing that decision to the Court of Common Pleas, with help from the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press [RCFP].

The county argued to the OOR that redacting only current undercover personnel names would allow someone to compare lists from various years and determine which employees were once undercover.

“The redaction is done in an attempt to shield the identification and disclosure of our members, as well as the chain of command, which could endanger the personal safety of these officers and make them and their families targets of the violent individuals they have or will seek to apprehend,” wrote county police Superintendent Christopher Kearns in an affidavit.

Sheriff Kevin Kraus declined comment, though his solicitor wrote in an affidavit that he would expect “certain individuals in the public” to use a dataset with fewer redactions to try to determine which officers were undercover investigators.

Rosalyn Guy-McCorkle, the solicitor for the county executive, argued in an email to PublicSource that the redactions are legal and appropriate and denied that they differ from the county’s past practices. The solicitor added that Sara Innamorato’s administration “has taken several steps” to promote transparency, including a dashboard showing how taxpayer money is spent and a “soon to be launched board, authorities and commissions tracker.”

Paula Knudsen Burke, the RCFP attorney representing PublicSource in the appeal, said the county’s actions have gone beyond existing protections for officer safety.

“What’s happening here is a sweeping attempt to hide a broader swath of public employees from accountability to the communities they serve,” she said.

Andrew McGinley, of the Philadelphia-based good government nonprofit Committee of Seventy, said there should be a balance between security concerns and transparency, and the path to such a balance often runs through the courts.

“The law provides for exceptions to protect safety in these specific areas, but those definitions clearly need to be clarified by the courts,” McGinley said.

Generally, he said, the public has an interest in knowing government employees’ names to hold elected officials accountable for how they allocate taxpayer dollars.

“As a citizen you have a right to know who’s working for the government and what roles they’re filling,” McGinley said.

The change in redaction policy means many more taxpayer dollars, including millions in overtime pay to public safety personnel, are shielded from public scrutiny. In the 2023 data provided to PublicSource, the names of none of the top 40 gross earners were redacted. In the 2024 data, 21 of them — earning a cumulative $1.3 million in overtime pay — were redacted.

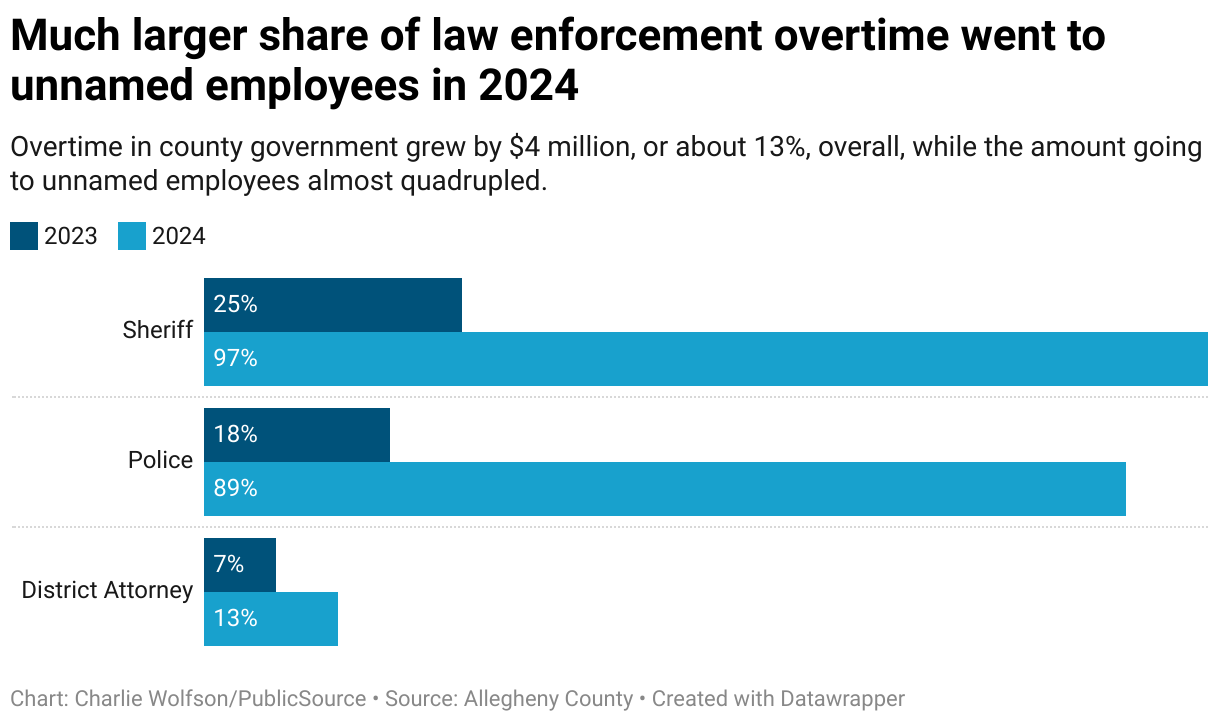

Overall, overtime pay was up in 2024 by about $4 million, reaching a total of about $36 million.

In 2023, the county reported $10.3 million in gross pay to employees whose names were redacted, including $1.4 million in overtime. For 2024, the county reported $46 million in gross pay to redacted names, including $6.7 million in overtime.

Of this year’s pay to unnamed employees:

- Just over half of overtime, or $3.9 million, went to 212 police officers

- Another $2.8 million in overtime went to sheriff’s department employees

- $2.6 million in gross pay, but little overtime, went to 24 unnamed employees in the district attorney’s office.

Across all three of the law enforcement departments, 90% of overtime pay went to redacted names. More than two of every three police officers’ names were redacted, along with those of 78% of sheriff’s office employees.

In 2023, the county redacted the names of just 89 total employees, or less than a quarter of the number from 2024.

Charlie Wolfson is PublicSource’s local government reporter. He can be reached at charlie@publicsource.org.

This story was fact-checked by Ayla Saeed.

This article first appeared on PublicSource and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.