The county had almost 100,000 people in 1950, according to census figures. More than one-quarter of that population was lost over the next decade and that number fell by 50,000 more in 1970. By 2010, it was 22,000.

As the mines that produced $1 billion in coal grew quieter, so did the cash registers. Infrastructure became a luxury. Unemployment rushed in. Alcohol followed. Drugs weren’t far behind.

“The problem at one point was alcohol. Through the last 15 years, I would guess, that problem has changed from alcohol,” said Judy Akers, chief executive officer of the Southern Highlands Community Mental Health Center.

Her organization’s clinic in McDowell County is treating 24 people for opiate addiction and has 143 others on a waiting list for the telemedicine program.

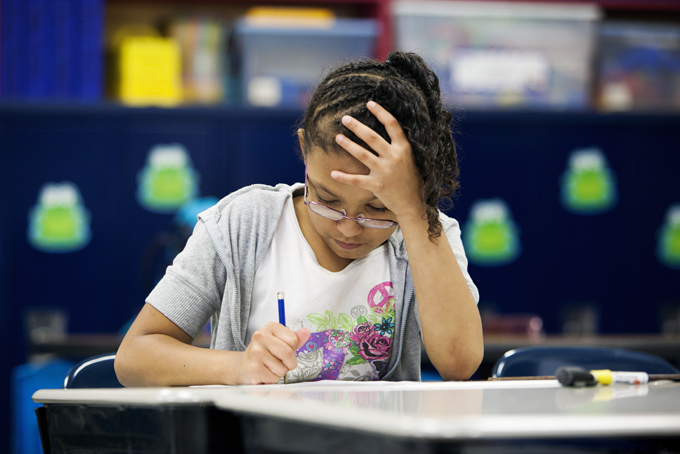

The drug problem become so severe that officials opened a juvenile program inside the school so teachers, already combating truancy, wouldn’t have to lose more students from their classrooms when they went for counseling.

“We have good people here. We have educated people here,” said Reba Honaker, the mayor of the county seat, Welch, and a former home economics teacher.

Just too few of them stay, she said.

Those who do leave behind statistics that make educators shake their heads.

Some 72 percent of the students live in a home where neither parent is working. About 46 percent of students live in a home without a biological parent; many of the parents are in jail for drugs.

Many of the students will become parents before they become graduates. The county leads the state in the teen birth rate, with roughly 1 in 10 females between the ages of 15 and 19 giving birth.

McDowell County has the highest death rate for prescription drug overdoses in the country. Twelve people die each month from abusing prescription pills.

Those are the extremes. On a more basic level, there are daily challenges.

Many of the students here have never sat in a dentist’s chair to have their teeth cleaned. There is no central water system so fluoride is not readily available, and it’s a long drive through treacherous terrain for anything beyond an emergency.

That will change next year if leaders can pull off their plan.

The Reconnecting McDowell leaders are trying to recruit dentists to work with the schools to set up medical clinics, not just for students but also their parents.

They’re also looking to expand the existing efforts to help parents’ reading skills.

The U.S. Department of Education estimates 22 percent of the adult population in the county lacks basic literacy skills. So project managers decided to introduce literacy centers not just for children, but also their parents and grandparents. At seven locations adults sit with educators and learn basic skills.

For others, there are home visits to help them learn reading skills.

“Parents want what’s best for their children,” said Jacki Wimmer, an early reading teacher who makes regular visits to seven families. “Some children come to school and they’ve never held a book.”

And for the traditional functions of a school? Those, too, need work.

Of the 350 teaching positions in McDowell County, 51 were not filled at the start of the school year. Those who considered moving here couldn’t find housing. In the mountainous region, there’s no flat land to build new houses. Rental property is hard to come by. The Reconnecting McDowell team is working on plans to build an apartment building to house 20 to 26 teachers.

In the short term, schools turned to substitutes and those who didn’t have licenses.

Despite the dour outlook, students and educators alike remain upbeat.

“I like my teachers. I like my friends. I like math,” third-grader Emma Cline said as she played in a computer lab after school, as she does three nights a week. “I really, really like that my teachers care about me.”

If leaders get their way, that care will take on even stronger efforts in coming years.

“You’ve got to look past the mold, the mildew, the trash and the dust,” McGuire, the principal, said as she walked through an abandoned gymnasium she hopes to turn into a community center. The outside doors were locked but the glass on one was broken so she let herself in.

“Think of how many kids could be saved here,” she said, kicking up dust with every step. “We have got to at least try.”