President Donald Trump speaks at a rally on Jan. 6, 2021, before the Capitol insurrection. Mande Ngan/AFP via Getty Images

by Amy Lieberman, The Conversation; Jeff Inglis, The Conversation, and Naomi Schalit, The Conversation

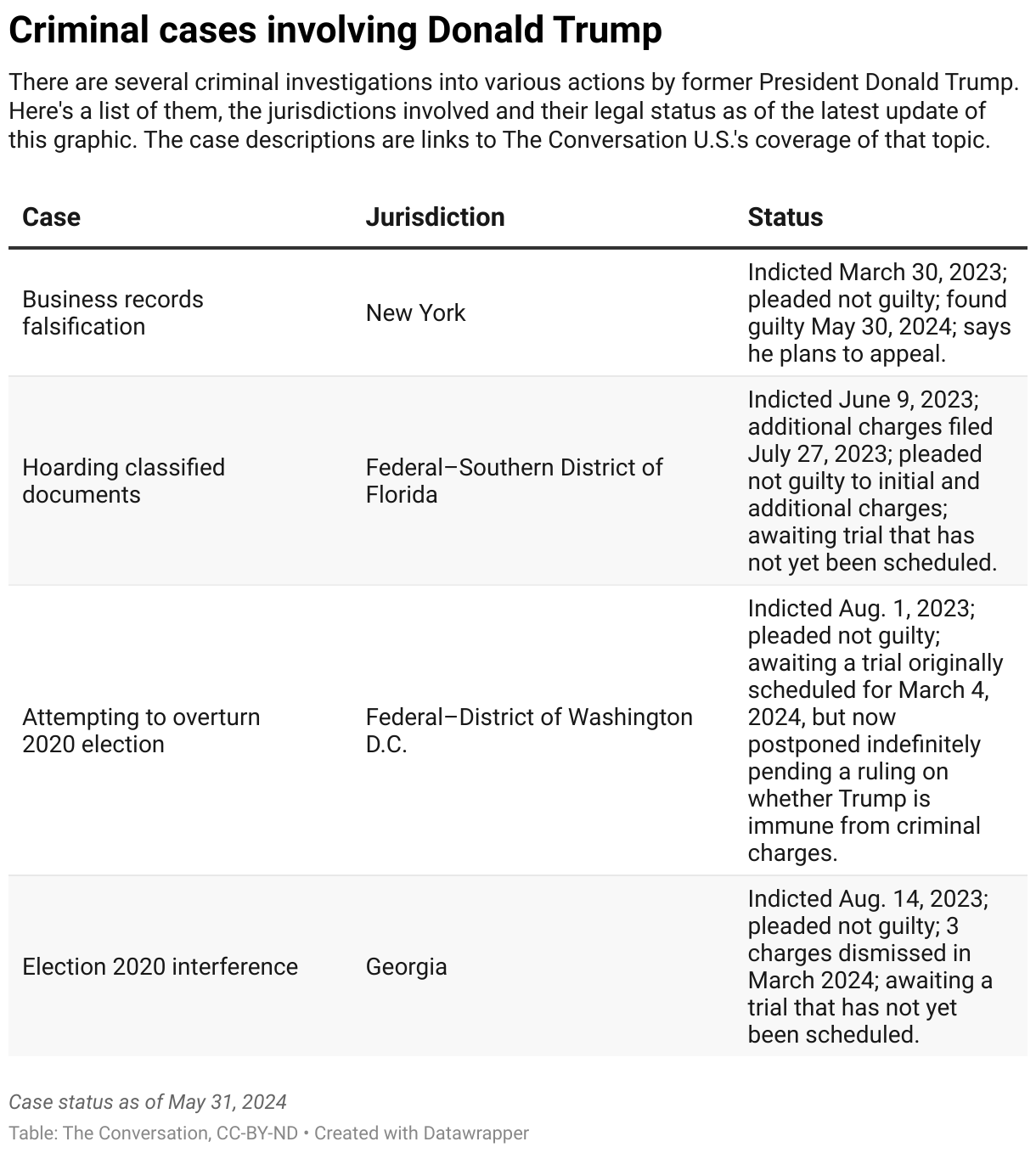

The U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that a president, including former President Donald Trump, “may not be prosecuted for exercising his core constitutional powers, and he is entitled, at a minimum, to a presumptive immunity from prosecution for all his official acts.”

The decision is “super nuanced,” as a law scholar explained to The Conversation shortly after the decision was announced on July 1, 2024.

While a president has total immunity for exercising “core constitutional powers,” a sitting or former president also has “presumptive immunity” for all official acts. That immunity, wrote Chief Justice John Roberts in the majority opinion, “extends to the outer perimeter of the President’s official responsibilities, covering actions so long as they are not manifestly or palpably beyond his authority.”

“There is no immunity for unofficial acts,” the court ruled.

The vote was 6-3, as the court’s three liberal justices – Elena Kagan, Sonia Sotomayor and Ketanji Brown Jackson – strongly disagreed with the majority opinion in a dissent.

“Today’s decision to grant former Presidents criminal immunity reshapes the institution of the Presidency. It makes a mockery of the principle, foundational to our Constitution and system of Government, that no man is above the law,” Sotomayor wrote in the dissenting opinion.

The federal prosecution against Trump for his actions to overturn the 2020 presidential election will now go back to lower courts to determine which of the federal charges against Trump can proceed. One outcome, though, is clear – this decision will have a major impact on presidential power and the separation of powers in government.

Until all of the decision’s nuances are parsed by constitutional law scholars, here are four stories to help readers better understand the arguments leading up to the decision and what was at stake with this case.

1. Laying the groundwork

Trump claimed he is immune from federal prosecution for his efforts to overturn the 2020 presidential election because he was in office as president at the time.

“Trump’s argument centered on a claim … that a president cannot be subjected to legal action for official conduct or actions taken as part of the job,” wrote Claire B. Wofford, a political science scholar at the College of Charleston.

Since 1982, in a case dating back to Richard Nixon’s presidency, presidents have been deemed immune from civil lawsuits based on their officials acts, Wofford explained, and Trump sought to expand that immunity protection. But it was a big ask, Wofford wrote:

“Protecting the president from the hassles of civil litigation is one thing; permitting the president, charged in Article 2 of the Constitution with faithful execution of the laws, to be able to break those same laws with impunity is quite another.”

Indeed, U.S. District Court Judge Tanya Chutkan wrote in December 2023 that Trump did not have the “divine right of kings to evade criminal accountability.” And a federal appeals court agreed in February 2024. That’s the ruling Trump appealed to the Supreme Court.

2. An inconsistent claim

Trump’s claim faced an uphill battle. Stefanie Lindquist, a scholar of constitutional law at Arizona State University, observed:

“In several of the lawsuits he filed challenging election results in the wake of the 2020 election, Trump himself said he was acting ‘in his personal capacity as a candidate,’ as distinct from his official capacity as president.

“Now, though, Trump claims that whether or not he was acting as a candidate on Jan. 6, his comments on ‘matters of public concern’ fall within the scope of his presidential duties.”

That inconsistency, as well as the general principle in the Constitution that no person could be above the law, made Trump’s position a difficult one to argue.

3. A decision a long time coming

Wofford, a constitutional law scholar at the College of Charleston, observed before the Supreme Court’s July ruling that there was public concern about the time it took the court to reach a decision, but she said that delay was much more likely in service of democracy than it was a partisan play:

“When the Supreme Court makes a decision, it is inevitably answering a very difficult legal question. If the answers were clear, the case never would have been the subject of high court litigation in the first place.”

And the task the justices have in deciding the case is vital to the nation, she wrote:

“(G)iven the potentially unconstitutional actions Trump has threatened to take if re-elected, the country will need a strong and well-respected Supreme Court in the very near future. Those angry with the court should actually be very glad it is working as usual here. If it weren’t, their fear that Trump will get away with it all may indeed be realized.”

4. What this means for the future

Earlier this spring, Wofford noted some disturbing portents during the oral arguments before the Supreme Court on April 25, 2024:

“Several of the justices, across the ideological spectrum, were very concerned about the practical implications of allowing a president to have immunity to some extent, or not allowing the president to have immunity.”

For instance, Wofford noted,

“Justice Samuel Alito seemed really concerned about the president being subject to political prosecution if he were not protected by immunity. … On the flip side … (Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson) said a president could enter office ‘knowing that there would be no potential penalty for committing crimes.’”

Wofford expected the justices would try to avoid granting either complete immunity or no immunity at all – and therefore allow Trump’s federal trial for attempting to overturn the 2020 presidential election to continue based on the fact that many of his actions were private, not official. Though that held peril, too, Wofford wrote:

“I wish there were a different vehicle through which the court could resolve this question and that it didn’t feel to so many people that the fate of our government, and the stability of our system, was on the line. … If it does not make a clear, resounding statement that the president is not above the law, then I think we have a serious problem.”

This story is a roundup of articles from The Conversation’s archives.

Amy Lieberman, Politics + Society Editor, The Conversation; Jeff Inglis, Politics + Society Editor, The Conversation, and Naomi Schalit, Senior Editor, Politics + Democracy, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.