The Chicago Defender Aug. 2, 1919 edition that chronicles the Chicago Race Riot.

As we embark on another Chicago summer, we revisit one of the most infamous incidents to unfold during this season 106 years ago—the Chicago Race Riot of 1919. The weeklong outbreak of violence left 38 people dead and more than 500 injured. Entire neighborhoods were shaken. The city’s racial fault lines, some still visible today, were carved deeper into the urban landscape.

Even then, The Chicago Defender was front and center—bearing witness, naming names, and telling the truth on behalf of Black Chicago. For our ongoing CD120 series commemorating 120 years of the Defender’s history, we bring you a conversation with Dr. Peter Cole, a historian who has made it his mission to study and elevate the legacy of the 1919 riot through education, public memory and art.

Cole, a professor at Western Illinois University and co-director of the Chicago Race Riot of 1919 Commemoration Project (CRR19), spoke with the Defender about why this brutal moment in Chicago’s past still echoes today—and how remembering it could help heal the city’s racial wounds.

The Defender’s First Draft of History

“We are who we are because of who we were,” said Cole, who has spent years researching how racial violence, inequality, and segregation shaped modern Chicago.

Back in 1919, no radio or television existed. Newspapers were the only source of mass communication. At that time, The Chicago Defender stood as one of the most powerful Black publications in the country—not just in Chicago but across the South, where its reach was broad and deeply felt.

“The Defender wasn’t just the largest Black newspaper in Chicago. It was a vehicle for information, for advocacy, for survival,” Cole said. “The name wasn’t random. It was there to defend the race.”

While White newspapers misrepresented the violence—often blaming Black Chicagoans for the unrest—the Defender named the victims, challenged false narratives and offered clarity amid confusion.

Cole added: “Newspapers are the first draft of history. And for a historian, there’s no better place to start than with the Black press.”

Remembering the Riot—and the People

Black and White soldiers facing each other in 1919 on street sidewalk (Public Domain Photo).

The CRR19 project, co-led by Cole, is a years-long public art and history initiative designed to ensure that the lives lost in the 1919 riot are remembered—and that Chicago doesn’t bury this chapter of its story.

That starts with names. All 38 victims—23 Black, 15 White—are being honored with artistic sidewalk markers at the sites where they were killed. The first five were installed at the intersection once called the “vortex of violence”—35th and State, near the Defender’s longtime home.

“We call it now the vortex of healing,” Cole said. “Because we believe this public art isn’t just about the past. It’s about helping the city move forward.”

Each glass marker is created by youth artists at Firebird Community Arts, many of whom are survivors of gun violence themselves. Each marker includes the name and date of the victim, and the project plans to install the remaining 33 bricks by the end of 2025.

Why It Still Matters

Though more than a century has passed since the riot, Cole sees the consequences of that week everywhere in modern Chicago—from the city’s segregation to its economic inequality and its enduring mistrust between communities.

“Living on the other side of the tracks is a Chicago story,” he said. “The violence of 1919 was about enforcing racial boundaries—and after that, they used tools like restrictive covenants to legalize segregation.”

The project also offers public tours, school presentations, and an online archive of all 38 victims’ biographies. Cole and his team host an anniversary ride each July that draws hundreds of cyclists from across the city.

But the ultimate goal is deeper than remembrance.

“We can’t heal until we acknowledge the past,” Cole said. “Forgetfulness has failed us. Now we need truth.”

Toward Justice, Not Just Memory

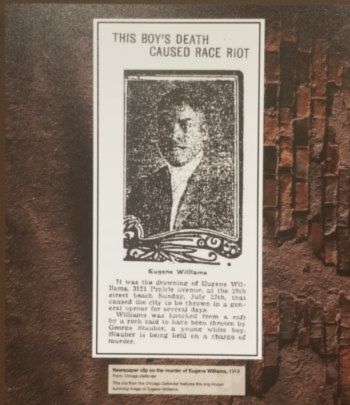

Eugene Williams, “The Boy’s Death Caused Race Riot”

Cole sees the project as a form of grassroots reparations—naming the victims, remembering their lives, and inviting the city to reflect on what must come next.

He hopes to eventually create a Eugene Williams Plaza near 29th and Lakeshore Drive, the site where the 17-year-old was killed for swimming in the wrong part of Lake Michigan. It was Williams’ death that triggered the riots—and he was the first of the 38 people to die that week.

“We don’t just want people to remember Eugene as a victim,” said Cole. “We want to honor who he was and what his story can teach us today.”

A Call to Action

The CRR19 project is funded by city grants and carried out by volunteer labor. Cole is joined by public health worker Franklin Cosey-Gay, youth advocate Saida Taylor and a network of artists and educators across the city. But there’s still much work to do—and they’re looking for help.

“We need tour guides, storytellers, artists, researchers—especially young people,” said Cole. “If you’re passionate about justice, history, or healing, we need you.”

For more information or to get involved, visit www.chicagoraceriot.org.

Watch the full interview on YouTube below:

As we continue our CD120 tribute to The Chicago Defender’s 120-year legacy, we remain committed to telling the stories that matter—just as we did 106 summers ago.