By Stephanie Gadlin, For The Chicago Crusader

In the early hours of Jan. 3, more than 150 U.S. military aircraft launched from 20 bases across the Western Hemisphere in what President Donald Trump called “one of the most stunning, effective and powerful displays of American military might” in U.S. history. The target: Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, who were seized from their residence on a military base in Caracas and flown to New York to face narco-terrorism charges.

While some Americans cheered the removal of a leader many viewed as a dictator, others saw the military operation as a continuation of U.S. colonization and global imperialism. The divide cuts particularly deep in Black American communities, where Venezuela’s decades-long support for African liberation movements and Black American causes has been largely erased from public memory.

“These actions have brought death and injury to civilians, desecrated the land and seas, and violated the nation’s sovereignty,” Black Lives Matter Grassroots (BLMG) said in a Jan. 4 statement to the Crusader. “Not only are these actions illegal according to international law and the United States Constitution, we know these to be war crimes and crimes against humanity.”

Trump made no attempt to hide his primary motivation during a news conference at his Mar-a-Lago estate in Florida. “We’re going to run the country until such time as we can do a safe, proper, and judicious transition,” Trump told reporters, in publicized remarks. “We’re going to have our very large United States oil companies, the biggest anywhere in the world, go in” to access Venezuela’s oil reserves, the largest confirmed reserves in the world.

Chicago Leaders Condemn ‘Unconstitutional’ Action

In Chicago, home to approximately 50,000 Venezuelan migrants who fled political turmoil and extreme poverty, elected officials sharply condemned the military operation as unconstitutional and driven by corporate interests rather than humanitarian concerns.

Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker, posting on social media platform X, called Trump’s action reckless. “Donald Trump’s unconstitutional military action in Venezuela is putting our troops in harm’s way with no long-term strategy,” Pritzker wrote. “The American people deserve a President focused on making their lives more affordable.”

Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson went further, connecting the raid to oil interests and warning of regional destabilization. “The Trump administration’s military action in Venezuela violates international law and dangerously escalates the possibility of full-scale war,” Johnson said in a statement to ABC7 Chicago on Jan. 3. “The illegal actions by the Trump administration have nothing to do with defending the Venezuelan people; they are solely about oil and power.”

U.S. Sen. Tammy Duckworth of Illinois, an Iraq War veteran and Purple Heart recipient, issued one of the sharpest rebukes from a military perspective. “Donald Trump’s reckless and unconstitutional operations in Venezuela, including this morning’s arrest of a foreign leader, are not about enforcing law and order because if they were, he wouldn’t hide them from Congress,” Duckworth said in a statement to CBS Chicago. “Maduro was unquestionably a bad actor, but no President has the authority to unilaterally decide to use force to topple a government, thrusting us and the region into uncertainty without justification. The Constitution requires the American people, through their elected representatives in Congress, to authorize any President to engage in acts of war.”

U.S. Rep. Robin Kelly, who represents Illinois’ 2nd District and is seeking a U.S. Senate seat, said Trump’s strike does “nothing to lower the cost of living for Americans” and does “everything to enrich himself and his billionaire oil-executive friends,” according to local reports. “Our focus should be here at home, lowering costs of healthcare, housing, and groceries.”

Hundreds of protesters filled Federal Plaza in downtown Chicago, calling the Trump administration’s actions an egregious overstep and a violation of federal law, according to CBS Chicago.

Malcolm X’s Vision: From Civil Rights to Human Rights

To understand why BLMG and others view the Venezuela invasion through a historical lens of imperialism requires going back nearly 60 years to when Malcolm X fundamentally changed how Black Americans viewed their struggle.

In his late 1963 speech “Message to the Grassroots,” the Muslim leader declared that “of all our studies, history is best qualified to reward our research.” This perspective shaped efforts within the Global South, including Venezuela and the Tricontinental movements, to contest colonial histories by recovering the agency of the oppressed.

By 1964, Malcolm X was advocating for “internationalizing” the Black liberation struggle. He viewed “civil rights” as a domestic, “hat-in-hand” compromising strategy that kept the struggle confined within U.S. borders. Instead, he called on African Americans to focus on “human rights,” connecting Black America to “dark mankind” globally.

Malcolm X proposed bringing the United States before the United Nations for its violations of human rights and genocide against African Americans. His reasoning was strategic: while Black people were the underdog on the “white stage” of America, on the global stage, the white man was a “microscopic minority” vastly outnumbered by dark people worldwide.

El Hajj-Malik Shabazz was assassinated on Feb. 21, 1965 and three days later, Pio de Gama, a Kenyan revolutionary who had met with Malcolm X during his African travels and was assisting him with his UN appearance, was assassinated in his driveway in Nairobi. The historic Tricontinental Conference in Havana , Cuba, listed the U.S. Muslim among “Tricontinental martyrs” alongside Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba of Congo and Mehdi Ben Barka of Morocco.

The 1966 conference also adopted a resolution condemning Malcolm X’s murder as “frenzied violence” by imperialists. His call for an UN-supervised plebiscite to determine the national destiny of the “Black colony” in the U.S. was directly incorporated into the Black Panther Party’s 10-point program established the same year.

Venezuela’s Concrete Support for African Liberation

The 1966 conference established real operational ties between Venezuelan revolutionaries and African liberation movements fighting colonialism. Venezuela’s Armed Forces of National Liberation sat alongside the African National Congress, the People’s Movement for Liberation of Angola, and Revolutionary leader Amilcar Cabral’s PAIGC fighting Portuguese colonialism.

Robert F. Williams, an African American exile who had fled FBI persecution for advocating armed resistance in North Carolina, drafted a resolution treating the Afro-American struggle as part of a global Third World project. Working with Venezuelan delegate Pedro Medina Silva, Williams cemented a Black American-Venezuelan revolutionary alliance.

The solidarity went beyond resolutions. Venezuelan revolutionaries joined a “General Secretariat” coordinating global revolutionary activity. Algeria’s FLN used a cargo vessel, the Ibn Khaldun, to ship armaments across the Atlantic to the Venezuelan FALN, bypassing U.S. surveillance.

These movements shared a “Third Worldist” worldview, seeing struggles in Vietnam, the Congo, Venezuela, and Angola as originating from “Yankee imperialism,” according to historian Anne Garland Mahler in “From the Tricontinental to the Global South.” They positioned “colonized peoples” as the primary force against global capitalism.

Amílcar Cabral’s “Weapon of Theory” became essential reading for Venezuelan guerrilla training, U.S. Black Power study circles, and Organization of Solidarity with the People of Africa, Asia, and Latin America networks. Ideas flowed from African liberation struggles to Venezuela to Black America and back. Cabral, called the ‘charismatic brain of the revolution,’ was assassinated by colonial agents and PAIGC infiltrators on January 20, 1973 in Conakry, Guinea.

Years later, Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez would cite Malcolm X as part of the “voracious reading of revolutionaries” that informed his Bolivarian mission. African American leaders like Harry Belafonte and Danny Glover drew direct parallels between Malcolm X’s struggle and Chávez’s Bolívar-inspired revolution.

Chávez’s Pan-African Internationalism in Action

The turning point came in 1989 when International Monetary Fund neoliberal reforms sparked mass uprisings. State forces massacred “dark-hued” barrio residents, creating a historical memory that Chávez, a part-Black and part-Indigenous military officer, mobilized against the “white oligarchy.” When the Bush administration backed a 2002 coup against Chávez, Afro-Venezuelan barrio residents led the counter-march restoring him to power. Opposition leaders used racist tropes, calling Chávez and supporters “monkeys” and “half-breeds.”

Once in power, Chávez reoriented Venezuela’s identity around its African and Indigenous roots and consistently expressed solidarity with Caribbean and African sovereignty. In 2004, Venezuela dedicated its first Bolivarian school to Martin Luther King Jr. in the predominantly Black town of Naiguatá. When Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans and the Bush administration rejected Venezuela’s aid, CITGO provided discounted heating oil to Black neighborhoods in Harlem and the Bronx as a “gift from the people of Venezuela.” The leader also held meetings with Rev. Jesse Jackson, Sr., Minister Louis Farrakhan, and Trans Africa spokesman and actor Danny Glover, where he reiterated his alliance with Black Americans and his offer of oil. Shortly after, a campaign spread in Chicago telling Black people to “stay away from Citgo” because “the gas will mess up your car (engine).”

The 2001 World Conference Against Racism in Durban forced Venezuela to admit racism existed, leading to the Network of Afro-Venezuelan Organizations demanding political power and reparations. By 2011, activists pushed through the Law Against Racial Discrimination, and the Census included “Afro-descendant” for the first time.

The Post-Chávez Vilification Campaign

When Chávez died in 2013 and Maduro took power, U.S. policy shifted dramatically. The Obama, Biden, and Trump administrations imposed increasingly severe sanctions on Venezuela, worsening its economic crisis in an effort to pressure regime change.

But the propaganda campaign proved equally important. As Venezuelan migrants fled economic collapse, partly caused by U.S. sanctions, right-wing media and politicians began promoting narratives about “violent Venezuelan gangs” like Tren de Aragua terrorizing American cities.

Trump repeatedly invoked racist stereotypes about Venezuelan criminals during his 2024 campaign, despite Venezuelans having lower crime rates than native-born Americans in most jurisdictions. The drumbeat of anti-Venezuelan rhetoric had a particular impact on African American communities already frustrated by local, state, and federal policies that failed to address violence and economic abandonment in cities like Chicago.

The irony is stark: Black Americans, many struggling with inadequate city services and gun violence, were conditioned to view Venezuelans as threats, the same nation that had given free heating oil to Black families in Harlem when their own government would not.

In Chicago, that came in the form of repeated news stories and allegations by the Trump administration that the U.S. had been overrun by Venezuelan drug cartels and gangs. Humanitarian aid to stabilize immigrant families was promoted as a sort of misuse and theft of taxpayer dollars and social services.

“They gave the migrants our money when we got homeless Black people on the streets,” one outraged citizen yelled at Mayor Johnson during a 2025 City Council meeting. “Those Venezuelan gangs are taking over buildings and getting money we can get…”

Coupled with the sight of Latino refugees and homeless people lying in the doorways of police stations and public libraries, Black Chicagoans had seen enough. When Trump ordered immigration agents to Chicago to round up “criminal illegal aliens,” most of whom were said to be Venezuelan gang leaders, African Americans, for the most part, remained silent as ICE agents were depicted in action.

“I felt like it wasn’t my issue,” said an unemployed African American 32-year-old man in Woodlawn who asked the Crusader to withhold his name. “They put them in our neighborhood and used all of our tax dollars to give them cars and furnished apartments, and they don’t do none of that for us. I was glad to get them out of here.”

When asked if he knew the history of Venezuela’s ties to Black movements, he said, “Nah, I never heard of that,” the man said, “and that was then, this is now. They (are) running drugs and getting our money and getting jobs and they (aren’t) even citizens. I was born here. I really don’t care.”

BLMG connected this pattern to historical U.S. interventions. “This is classic U.S. colonialism. It is the same racist, imperialist playbook that has been used to kill or remove elected leaders who refuse to comply with the will of the empire,” BLMG said in its statement. “U.S.-orchestrated ‘regime change’ has plagued Africa, the Caribbean, and Latin America throughout the 20th and 21st centuries in places like Guatemala, Brazil, Chile, El Salvador, Grenada, Haiti, Congo, Ghana, and Libya.”

The Trump administration justified the operation on narco-terrorism grounds, charging Maduro with presiding over a “narco-state.” Yet just weeks before Operation Absolute Resolve, Trump pardoned former Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández, who was serving a 45-year sentence for drug trafficking, identical charges to those leveled against Maduro.

Dr. Ana Gil Garcia, founder of the Illinois Venezuelan Alliance, expressed cautious hope tempered by uncertainty about Trump’s intentions. “We can’t really celebrate something that we don’t know in what direction this is going to go,” Gil Garcia told WGN-TV. “We don’t want anybody to run our country. We want Venezuela to run our country.”

A Pattern of Imperial Intervention

The capture of Maduro follows a well-documented pattern of U.S. intervention against leaders who sought to redistribute wealth or nationalize resources. In 1954, the CIA orchestrated the overthrow of Guatemalan President Jacobo Arbenz after he attempted land reform that threatened the United Fruit Company. In 1960, U.S. intelligence was involved in the assassination of Patrice Lumumba in Congo after he sought to keep Congo’s mineral wealth for the Congolese people. In 1973, the U.S. backed the coup against Chilean President Salvador Allende after he nationalized copper mines.

Trump made the oil motivation explicit in his Jan. 3 news conference. “Venezuela was about to collapse. We would have taken over it … [and] kept all that oil,” Trump told reporters in a 2023 press conference, according to Wikipedia. Hours after the attack, Trump said U.S. oil companies would spend billions fixing Venezuela’s energy infrastructure “that they developed decades ago, until socialist regimes nationalized their wells.”

According to the Center for American Progress, Trump pressed oil and gas executives to raise $1 billion for his 2024 campaign, promising he would deliver on their policy priorities if reelected. The industry contributed at least $96 million directly to Trump’s campaign and super PACs.

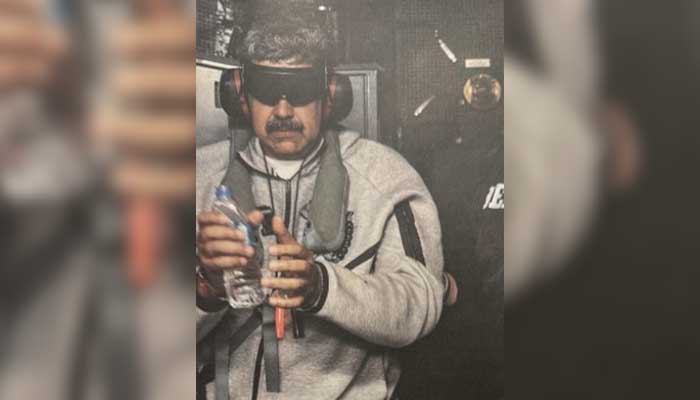

Gen. Dan Caine, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, detailed the massive scope of Operation Absolute Resolve during the Jan. 3 news conference. More than 150 aircraft, including F-22s, F-35s, F-18s, B-1 bombers, and drones, were involved, according to Fox News. U.S. forces reached Maduro’s compound at 1:01 a.m. EST on Jan. 3 and were safely out of Venezuelan airspace by 3:29 a.m. EST.

Venezuela holds the world’s largest oil reserves at 303 billion barrels (17 percent of the global total) but produces only 960,000 barrels daily due to sanctions and underinvestment. Nine days earlier on Christmas, Trump ordered airstrikes on Nigeria, which produces 1.5 million barrels daily with just 37.5 billion barrels in reserves and received limited strikes with government cooperation, not invasion.

Venezuelan Vice President Delcy Rodríguez, who under the law became acting president, characterized the operation in explicitly racial terms. She denounced the capture as a “Zionist kidnapping” intended to restore a colonial “white order” and strip away the racial gains of the revolution, according to research documents.

Gov. Pritzker’s concerns about the lack of a long-term strategy echoed warnings from military analysts. “This is exactly the euphoria we felt in 2002 when our military took down the Taliban in Afghanistan,” Rep. Jim Himes, a Connecticut Democrat, told CBS News. “In 2003 when our military took out Saddam Hussein, and in 2011 when we helped remove Muammar Qaddafi from power in Libya.”

Cuba in the Crosshairs

Trump’s threats extended beyond Venezuela. The operation killed at least 32 Cuban nationals who were in Venezuela, according to Cuban officials cited by ABC News. Trump used the raid to threaten Cuba directly. The Caribbean island, just 619 miles from Florida, has long been seen as an ally of Black American and African freedom movements.

The nation, which gained its independence from U.S. control under the leadership of Fidel Castro, became a bastion of asylum for Black revolutionaries such as Black Liberation Army leader Assata Shakur, who escaped to Cuba in 1979. The underground leader, who escaped from prison, remained there until her death on September 25 of last year in Havana at the age of 78.

“Cuba is ready to fall. Cuba looks like it’s ready to fall. I don’t know if they’re going to hold out,” Trump told reporters on Jan. 5, according to ABC News. “But Cuba now has no income. They got all their income from Venezuela, from the Venezuelan oil. They’re not getting any of it.”

Secretary of State Marco Rubio, a Cuban American who has long opposed the Cuban government, was even more explicit. “If I lived in Havana and worked in the government, I’d be concerned,” Rubio told NBC’s “Meet the Press” days after the attack.

Scholars note that Rubio’s primary interest in the region has always been Cuba. “Marco Rubio’s primary interest in the region is not Venezuela, it’s not Colombia, it’s not Mexico. It’s Cuba,” Alejandro Velasco, an associate history professor at New York University, told “Democracy Now” on Jan. 5. “As a Cuban American and long, stridently an opponent of the Castro government, he’s made no secret of his desire to oust the government in Cuba.”

For years while on various campaign trail, the secretary claimed his parents were “exiles” who fled Castro’s takeover. However, Rubio’s parents Mario, a bartender, and Oriales a stay-at-home mom, left Cuba in 1956, during the corrupt regime of Fulgenio Batista, more than two years before Castro’s revolutionary forces removed the elitist, authoritarian ruler and gained power in 1959. When fact-checked by the Washington Post, Rubio clarified his narrative and accused family oral history for the discrepancy.

Still, the U.S. seemed poised to control or seize Cuba.

U.S. activists and leaders were not surprised Cuba was next. “The U.S. is deathly afraid of the Bolivarian Revolution, solidarity among Black and Brown nations and people, Venezuela’s socialist potential, and what it could mean for Latin America and the world at-large,” BLMG said in its statement. “We remember Venezuelan leader Hugo Chavez, the Afro-Indigenous socialist, who inspired the people to own their collective power.”

Mayor Johnson also echoed concerns about the treatment of migrants. “As we have said for the past two years, the dehumanization of migrants from Venezuela, and of immigrants generally, by the Far Right has laid the groundwork for military action in Central and South America,” Johnson said in his statement. “I strongly condemn the Trump administration’s inhumane treatment of migrants in our country and this illegal regime change abroad.”

Prisoner of War or War Criminal?

Maduro and his wife were arraigned in Manhattan federal court on Jan. 5, pleading not guilty to charges of narco-terrorism conspiracy, cocaine importation conspiracy, and possession of machine guns and destructive devices. During the arraignment, Maduro characterized himself as a “prisoner of war” and maintained that the charges were a pretext for an illegal kidnapping and “imperialist aggression,” according to court documents.

The charges were built upon an initial indictment from March 2020, when the Trump administration first sought to prosecute Maduro. In 2020, a failed attempt by Venezuelan dissidents and American mercenaries to overthrow Maduro, known as Operation Gideon, had the support of the Trump administration, according to mercenary leader Jordan Goudreau.

Thomas Mockaitis, a history professor at DePaul University, told ABC7 Chicago on Jan. 3 that he worries about the precedent. “If the United States can get away with doing this, how do we look Vladimir Putin in the eye and say, ‘You can’t invade another country. You can’t replace somebody just because you don’t like him?’” Mockaitis said. “He’s gonna look at us and say, ‘Why can’t we?’”

For Chicago’s estimated 50,000 Venezuelan migrants, many of whom fled the very conditions partly created by U.S. sanctions, the raid creates profound uncertainty. The excursion also exposes a painful contradiction: How did a nation that once gave free heating oil to Black Americans in Harlem, that supported African liberation movements fighting colonialism, that dedicated schools to Martin Luther King Jr. become vilified as the enemy in Black American consciousness?

The answer may lie not in Venezuela’s transformation, but in how imperial powers use propaganda to turn oppressed peoples against their historical allies.

Following the arrest of Maduro, Trump announced on Jan. 7 that Venezuela agreed to deliver “a few months’ worth of oil to the U.S.,” though Acting President Rodríguez initially denied any deal exists, saying “no external agent” was dictating her decisions, according to a national news report. Trump said the U.S. would “run” Venezuela until there was a transition of power, though these claims were contradicted by Rodríguez and later walked back by Rubio.

The question for some is whether the American people, including Black Americans with historic ties to Venezuela’s revolutionary solidarity, will recognize a troubling pattern now that Cuba is in U.S. crosshairs.

“As we condemn this violent, horrific display of U.S. imperialism, we call on all people of conscience to resist,” BLMG said. “May this mark a moment of international working-class solidarity and global uprising. May it offer an opportunity to use the earth’s resources for the good of the people, not to satiate the greed of the rich.”

About the author

Investigative Reporter (Freelance)atCrusader Newspaper|773-752-2500|sgadlin@chicagocrusader.com|Web

Stephanie Gadlin is an award-winning, independent investigative journalist whose work blends historical analysis, data reporting, and cultural commentary. Her work is published in the Crusader and other publications across the country. She specializes in uncovering the intersections of Black culture, public health, environmental justice, systemic racism, public policy and economic inequality in the U.S. and across the African Diaspora. For confidential tips, please contact: voiceandshield@proton.me